Over their decade long run, mobile 4X strategy games, sometimes known as SLGs, have brought in billions of dollars in revenue with only more to come.

For those wanting to get in on it, the history of these games is littered with both progress and mistakes that any hopeful successor would be wise to learn from. Their history may even foretell where the next generation of these games will go, and what the secret sauce of the next big one will be. You just need to know where to look.

Where am I coming from? Over the past nine years, I've played an array of 4X strategy games at a very hardcore level. Even as a player who doesn’t spend on IAPs, I’ve been the #1 player, led top clans, and sold my accounts for a tidy four figures. That’s the outside perspective I bring.

The inside perspective? I was the founding developer that led a team of engineers to build one such game, and was hands on for its conception, through prototyping, launch, and beyond. I can’t discuss internal numbers of course, but nothing’s stopping me from discussing external ones.

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

In the beginning, the strategy games in the appstores were quite light. Games such as Kingdoms at War succeeded in reaching the top grossing charts. These were forebearers to what I'd consider the first real 4X strategy games on mobile. They had buildings, and armies perhaps. You could fight and interact with other players, and there might've even been PvE. But there was no world map. No physical world the players resided in.

There were PC and web-games that had this to be sure, but those hadn't made the move to mobile, at least not yet.

There are far too many games in the genre for me to count let alone play to a deep enough degree. However, the seven I’ll go over paint an overall picture of the genre's history over a large time span, and will give us a perspective into what's worked, what hasn't, and what's to come. Let's get to it.

Kingdom Conquest

Kingdom Conquest

[November 2010]

This was the first game I played in this space. A lesser-known title from Sega which saw some decent success for its time, making it high into the top grossing charts. It had the prerequisites. Upgradeable buildings, ten levels each. Armies, themed as trading cards. Eye candy for UA in the form of 3D PvE encounters, though players quickly found out it was just a facade for a loot box. But most importantly, it had a world map, and the emergent behaviours that it brought to the table. Already a staple in the web-based games of the genre, this was one of the early implementations of world maps on mobile. It was a great game. I played the hell out of it. Unfortunately it had a fatal flaw that limited its lifespan and doomed it. More on that to come.

City Building in Kingdom Conquest

Eye candy, which didn't do much for gameplay, but helped with user acquisition

From the very start, this genre of games had a tight, addictive NUX. Quests guide the player’s actions. Return notifications call players back again and again. New mechanics are introduced keeping things interesting, and giving players milestones to strive for.

Kingdom Conquest's fatal flaw however was that they structured the game based on a short, finite season structure. After battling it out for multiple months, with a winner declared, player progress was reset. Not only this, but content was naturally structured with this in mind.

As many in the industry will know, the majority of the potential revenue from users comes from the tiny proportion of spenders who decide to spend a lot: the whales. To capture this full potential however requires time. Players can play for years and years, but artificially capping their lifespan slashes the full potential of this LTV.

As can be imagined, after a season reset, only a fraction of players return with the same interest and intent to spend. Any player would temper their spending in the game once they found out that even if they "won", it'd all be gone within a few months. Maybe it was a worthwhile experiment to try at the time, but it was a severe handicap in the end.

A brief lull in the genre followed until early 2012.

Kingdoms of Camelot: Battle for the North

Kingdoms of Camelot: Battle for the North

[March 2012]

Here was the first mobile game in the genre that hit it big in this space. This was the mobile incarnation of what was already a Facebook success.

To the formula we had already seen in Kingdom Conquest, Kingdoms of Camelot added a few new things to the mobile mix. A distinct, though limited, research tree. Multiple player-owned cities. Simple heroes. Simple map PvE.

Building upgrades also included a minor twist, where players who wanted to fully upgrade the building to level 10 needed a premium item to do so. One which cost them premium currency, available through in app purchases.

However, despite the additional systems, the game proved to be less effective at monetization than future successors would be.

Their heroes, while a nice addition were simplistic and not fleshed out at all. Skipping the fine details about how they worked, players desired the benefits they provided, and would pay for them, but the shallow way they worked combined with the cost ceiling left a great deal of potential on the table. The limited research and useless PvE came with similar criticism. They were shallow and the game subsequently wasn't as effective at monetization as it could be.

The ability for players to own multiple cities was an interesting advent as a way to try to stretch out the content, something the web-based game also made use of. But really it wasn't necessary, as future takes on the genre would find: a single city with better-balanced building progression was cleaner, and better yet, was more conducive to monetization. Moreover, managing multiple cities was frankly tedious.

The emergent behaviours and PvP threats in the game world were also limited by a Kingdoms of Camelot-specific mechanic where players could opt to “hide” their troops, making them impervious to military losses. The resources in their city would be free for the taking in the meanwhile, but those were fairly easy to acquire. As a result, certain opportunities for conflict and the monetization that comes with it was lost altogether.

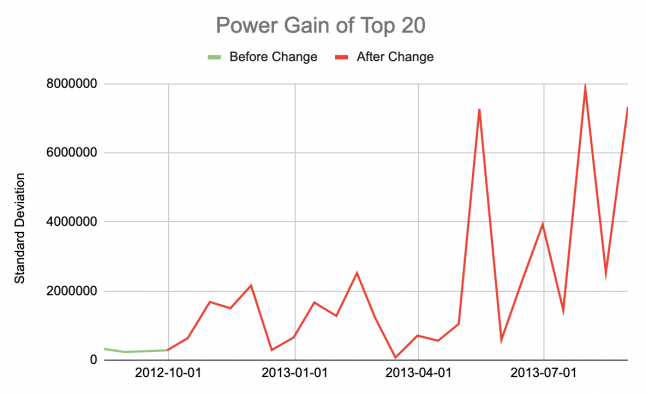

In an attempt to better monetize the game, part way through its lifespan the developers decided they'd allow troops to be directly purchased. Certain players loved this to be sure, and short-term revenues shot up as the ineffectively monetized players found an avenue to spend. But such an approach totally circumvented the rest of the game's content and balance. It was a tacked on lever that was completely disconnected from the rest of the game, with a high potential to break it, which it sure enough did. The game's leaderboards and community was subject to an inevitable p2w death spiral from which entire shards would never recover.

Imbalanced monetization resulting in unstable community and p2w death spiral (data from first shard)

As an aside, some of this data is available in part because of how easy it was to decompile Unity builds in the past, allowing enterprising individuals to bypass API security checks the game server had in place. One such individual used this information to build a site that periodically scraped game information, allowing players to do game-breaking things such as easily searching for player city locations on the map.

Despite its shortcomings Kingdoms of Camelot found success at the time as it stood above its rivals, and it would spin off skins such as The Hobbit: Kingdoms of Middle Earth.

The games that would follow it though made up for these shortcomings, with better fleshed out systems and deeper content to match. These successors would reap the benefits of far higher LTV ceilings as a result.

Game of War

Game of War

[July 2013]

Game of War offered a big step up. The simplistic systems of the previous generation were taken, and properly fleshed out, while weaknesses were shored up, and brand new competitive features added.

To start off, let’s go over the added depth. A hero avatar was introduced, with a fleshed out skill tree and equipment to match. Both the city and research content was now much deeper, offering a deeper progression path to both strive and monetize for. And the world map was now livelier, with more to observe and engage in. Player marches were now visualized, something absent in past iterations, resources could be gathered, and PvE was actually useful and rewarding. A player seeking more strategy in their games would find it here.

On the whole, the balancing seemed to have kept a better eye on player goals, and as a result they did a better job monetizing the critical path players take in the game as they build out their city and research the top tier troops. While in previous games an engaged player could pretty reasonably complete their city and attain top troops, it now took either considerable time and effort, or more likely, money, to achieve the same. Every successful game to follow would take a similar route.

All of these advancements together made for a deeper and more engaging game, which reaped far better LTVs.

To top it off, significant end game features were added, creating sources of conflict and goals for the biggest spenders. This came in the form of Wonders, a sort of clan-pvp king of the hill, along with shard vs. shard events, commonly referred to KvK. Both made use of added rallying mechanics, enabling the joint attack and defense of clan members and structures.

Wonders and Marches as implemented in Game of War

The basic formula laid out by Game of War would be carried forward in some form in all of the genre's successors to come. A new baseline had been set.

Outside of the game, Game of War was able to fully exploit its LTV advantages with tremendous UA efforts, including its infamous Kate Upton TV spots. Many in the industry questioned how they could be acquiring users profitably with the amount of spend here, but in the end, it's undoubtable how much of the market they captured as they had a solid position on the top grossing charts for a considerable stretch of time.

As time marched on though, cracks emerged. This was marked most significantly by the way live ops constantly pushed the economy and the game's players to the breaking point. Expensive whale content was frequently refreshed, which made older content obsolete, while at the same time aggressively inflating the economy.

It's impossible to say if this might've been the right move from an LTV standpoint. Their strategy was to aggressively suck out as much money as possible from players while they were still engaged, perhaps as a way to try to recoup their UA costs as soon as possible. What is clear though is that as this became more drastic, this was the specific thing that started to drive more players away, even their most dedicated whales. An informal survey of whales placed this as a top concern. Attempts to improve LTV may have backfired in the end.

Machine Zone, the makers of Game of War, would later try to run the same playbook with games like Mobile Strike and Final Fantasy XV, but a combination of a dated engine, mismatched expectations, and perhaps a change in the market limited the success of these endeavors.

Clash of Kings /

Clash of Kings /  March of Empires

March of Empires

[June 2014 / August 2015]

The next major iteration on the genre came with the advent of clan-controlled territories on the map.

Games like Clash of Kings saw significant success here. Unfortunately this wasn't one of the games I chose to pick up during this period as I was deep in the game development grind. However, observing colleagues playing the game and reading up on the details it's clear it was a meaningful step forward and laid the ground for new sources of large scale organic conflict on the world map.

Here, clan members could work together to construct structures on the world map, which provided benefits and new capabilities to members within it.

Many games now have their own take on territory, and it's something that's still evolving. The game I did play during this time that tried to tackle territory in its own way was March of Empires, which saw only very limited success. Its take involved fixed territories and buildings on the map, as opposed to something more organic. Clans can take over these territories and buildings, which provide dwellers with advantages.

These different variations are perhaps a good example of some of the risks involved when exploring an untapped design space. While territory in Clash of Kings proved quite successful, the implementation in March of Empires felt lacking. It isn't sufficient to just try something new, you still have to get it right.

Regardless, territory mechanics were a meaningful advance forward, and something which various successors would continue to take up.

Lords Mobile

Lords Mobile

[February 2016]

Then came Lords Mobile.

The two most obvious steps forward were:

The more casual-friendly, "Heroes Charge"-like mechanic they grafted onto the game, which was ornamental in many ways but helped ease players into the on boarding until they could transition into the real 4X game.

The much improved UX and friendlier, less-hardcore art style. Early games were often clunky to navigate, with a gritty medieval art style that could turn off many potential players.