(you can find the original article here)

You've done it. You made the jump. You've gone from "just working on a project," to identifying yourself as a real-life game designer. You've got a solid game design document, a (mostly) working prototype, and have even started to deal with the incredulous looks of bewilderment and disbelief when you tell people you're "making a game".

As you consider your wild fantasy of a design, the gravity of what you've signed yourself up for BEGINS TOi DAWN ON YOU:

"What have I been doing?" "Is this even possible?" "Am I crazy?"

These are among the frantic questions that race around your mind. Every time you find yourself thinking about letting your hopes of making your game die, you remember: You are a game designer, and this game deserves to exist.

I put together this list to share how I've coped with the affliction of being a game designer. As Renaissance Man Kanye West put it, "this shit was hard to do, man!". Everyone has a unique environment, circumstance, and perspective when it comes to creating art--video games are no different.

Even though these suggestions won't work for everyone, I've tried to think of things that can apply to every indie designer, regardless of who they are and what game they are designing. You should also know that I've broken every one of these rules at some point during development myself. So, don't beat yourself up -- with these suggestions, starting late is much better than never!

1) Keep going

<iframe title="Embedded content" src="https://giphy.com/embed/1iTH1WIUjM0VATSw" height="270px" width="100%" data-testid="iframe" loading="lazy" scrolling="auto" data-gtm-yt-inspected-91172384_163="true" data-gtm-yt-inspected-91172384_165="true" data-gtm-yt-inspected-113="true"></iframe>It seems insurmountable.

First, there's thinking of a way to craft your game that doesn't feel the same as everything else in the genre. That's before coding billions of mirco-conductors to manifest the wild fantasy of you've envisioned.

After that, you have to make sure it's good--even something as simple as moving a character around a 2D plane may need dozens of iterations to be balanced properly. As a designer, you don't ship with your game. Early in the process, you have to consider if the player can actually figure out what they're doing without you hawking over their shoulder. This issue is addressed through the use of designer-player communication tools like the GUI, prompts, and message windows.

The fact is, as an indie designer there will always be a million things to do. A lot of times at least half of them are going to seem impossible. A great game design professor once told my class that the "design never ends," despite the fact that the game has to ship at some point. What defines an indie game designer is the willingness to face these odds through failure, disappointment, and ridicule.

Just remember: keep going! In my experience, indie development works great in combination with "tunnel vision," or the ability to ignore and look past distractions and other exterior actors and concentrate on the goal or task at hand. Remember why you chose to do what you do in the first place. Remember how you've already come as far as you have, and consider why the world needs your game.

2) Make lists

<iframe title="Embedded content" src="https://giphy.com/embed/BBkKEBJkmFbTG" height="270px" width="100%" data-testid="iframe" loading="lazy" scrolling="auto" data-gtm-yt-inspected-91172384_163="true" data-gtm-yt-inspected-91172384_165="true" data-gtm-yt-inspected-113="true"></iframe>

During my university career, I was once told that "humans are monkey-minded". The notion has stuck with me. I remember the lecturer explaining how our mind naturally skips from thoughts, to memories, images, and everything in-between. A primary role of our self-conscious is in mediating and ordering this "monkey-mind" so that we can do things like have conversations and file our taxes.

Not to too get super Dalai-Lama here, but both creativity and the path to a state of peace and contentment are empowered by giving freedom to the monkey-mind. Of course, there are times where the monkey really should be paying attention, but even if you have to wrangle it in, it's only kind to be gentle, right?

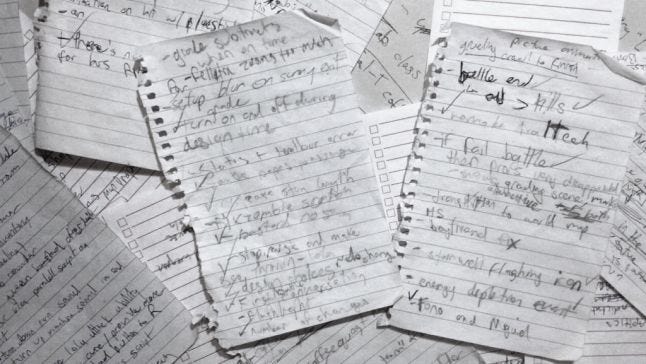

To get to the point--lists are a great way of allowing yourself to be creative. And remember, the lists don't have to be exhaustive--you can always make another one! Make a list for your tasks for the next month, the next day, the next build, or the current character you're making.

As I stated before, there's a lot going on when you are developing games--especially on a small team or by yourself. It creates a lot of baggage -- you can be constantly trying to recall details of bugs you need to fix, or details of an art asset that needs to be changed. Committing the things you need to do to paper allows you to release those thoughts so that they don't have to take up space in your mind. That way you've got much more room for your monkey to wander and gather the fruits of creativity!

Also, give yourself the satisfaction of checking, crossing off, making a blood oath, or whatever it is you want to do to the list to communicate to yourself that a task is done. No matter how big or small of a task, use it as an opportunity to celebrate. It was on list, and now it's done. You fucking did it! You are a little bit closer to bringing your game into reality.

(Please don't actually do a blood oath, it's unsanitary.)

3) Take breaks

Remember the "fun meter" from the Sims? It's a real thing! Respect your fun meter.

Sometimes that might mean giving yourself a night off to decompress after banging your head against a wall for hours trying to fix that collision bug--maybe by switching to something like writing blog posts or by watching "Indie Game: The Movie" or an episode of Double-Fine Adventure. Do what you can to get yourself back into the zone. If you can work in a positive state of mind, both your work and efficiency will benefit as a result!

Good games take sacrifices of relationships, money, and perhaps most importantly--your time! So make sure you are managing your energy and putting some time into maintaining your physical and mental well-being. After all, if you're unwell it's harder to make a game!

4) Use Naming Conventions

Anyone who’s been hundreds of files deep into development and managed to lose that crucial asset that they've worked on for hours will stress how important this point is.

Proper use of naming conventions will save you a world of time and frustration. Your method doesn’t have to be too elaborate as far as “professional” conventions" go, but your main considerations should be consistency, clarity, and convenience. Whatever system you decide to use, make sure it’s logical and predictive for you. If someone else were to make an asset for your game using your naming conventions, you should be able to tell what kind of asset it is in your game, and where it belongs.

It can be very simple, but must be enough to make your assets distinguishable. It’s also important to carry this relationship with naming conventions across your whole project! For me, this includes art assets, scripts, and even the images I use for blogging. They might change from subject to subject, but the main thing is to make sure you know, and understand it, while finding your system efficient.

5) Talk to people

Developing Class Rules has been one of the most isolating experiences of my life. Making a game is itself a profession that is already at odds with society's "norms" and expectations of what constitutes wage labour and otherwise normative ways of life. Further, the actual day-to-day process of developing games is alien to the vast majority of people. Attempting to explain the minutia of "the awesome new script" you're working on, current hiccups in the coding process, or the labours of trying to balance a level often results in a glazed expression of confusion and apathy.