Strategy game designers should start thinking about alternatives to “score systems” for their games. In this article I will talk about how and why we use score systems right now, what their weaknesses are, and how we can (as well as why we should) move beyond them. Much of this article is written with respect to designing single player strategy games, but the theory absolutely applies to multiplayer strategy games equally.

Score Systems in Videogames

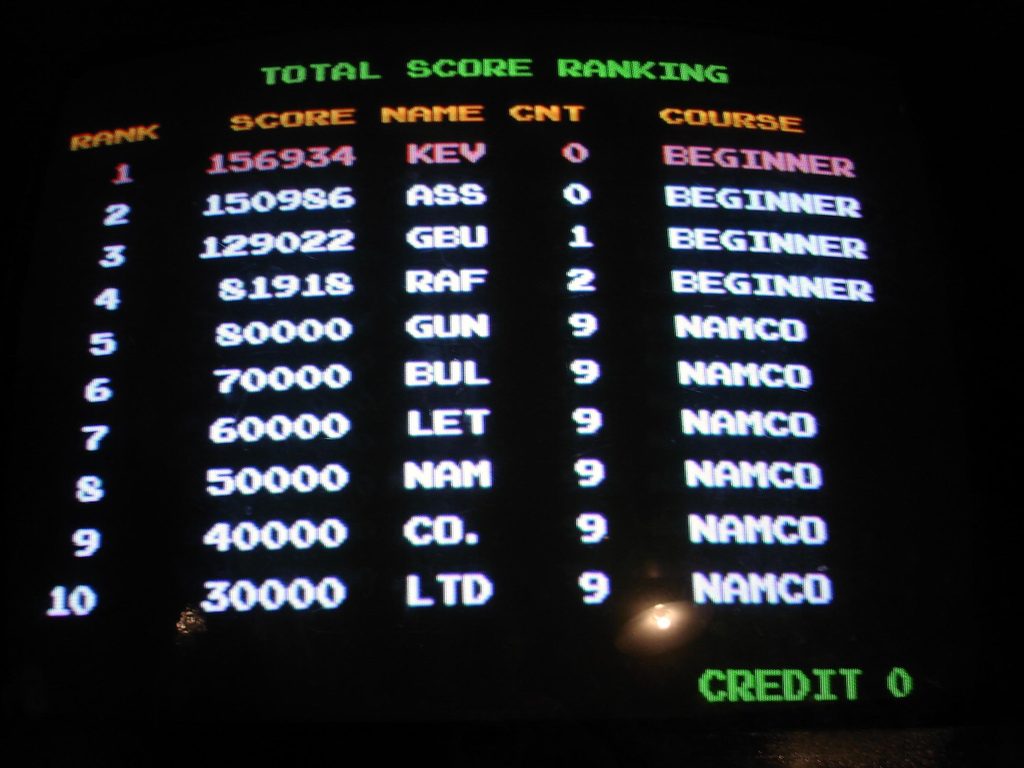

Score systems have been relied on by all kinds of interactive systems designers since the beginning. Early videogames such as Pac-Man and Galaga had high score boards that players would compete for places on, whereas Super Mario Bros. had a score feature as a sort of extra added feature that really serious players could try to maximize if they got tired of beating the game.

It goes back further than that, of course. Pinball, which laid many of the foundations for videogame design tropes, also used a score system, not to mention some ancient games such as Go. Today, there are strategy games that use score systems, such as games like Civilization, Rogue-likes, or my own Auro: A Monster-Bumping Adventure. They’re appealing to designers because they’re so simple to implement and design; you can pretty easily take just about any simple toy/sandbox activity and slap a score on it, and then it almost instantly feels a little bit more competitive, a little bit more replayable, a little bit more “strategy-game-like”.

I think I can classify the usage of score systems in videogames into three categories. Later, I will propose a fourth.

Category #1 – “Completion Systems”

This type is least relevant to the current article, because its score (if it even has one) is more or less irrelevant. These are systems that may have a score, but also have some other unrelated binary goal that most people pursue (Super Mario Bros., arguably Rogue-likes, any story or puzzle-based system). To the degree that Super Mario Bros. states its goal, I believe it’s to “rescue the Princess”, and I think that that’s how most people play the game. Rogue-likes perhaps a bit less so, since completing them is often very difficult. But most people do describe Rogue-likes as “really hard” and say things like “they’ll kill you over and over”, sort of suggesting that they believe completion to be the goal. It’s also worth noting here that videogames have trained most people to think along the lines of completion; “beating the game”, and so on, so if a system has both a score and completion, people will tend to go for the completion for that reason (as well as another that I’ll get into later). It is particularly useful for story-based systems and lends itself to a system that is designed to be “consumed”; played once and then discarded, more or less. It is equally useful for puzzles for the same reason.

Completion is different from a “score”, in that it’s binary. A score can be any number, but completion has just two states: completed, or not completed. Granted, these days, completion is a lot blurrier, with multiple endings, extra content and so on, but the principle of “beating the game” as a basic design idea still mostly holds up.

Completion is also different from winning. While both completion and winning are binary outcomes, completion marks a point where the user is largely done with the entire system, whereas winning is just a tiny notch in the long life of a usually highly replayable system.

Category #2 – “High Score Systems”

These are systems that output the number at the end of play, without giving you any kind of “win/loss” or “completion” feedback along with it. Classic Tetris comes to mind; one never “wins” (at least not in the single player mode) in Tetris. You play, and at some point the play session end is triggered, and at that point you are given a number that reflects the number of combos and a few other factors.

These have been the most prevalent among strategy/competitive-ish kinds of videogames. Like I said before, it’s largely because it’s easy and extremely flexible. It’s much harder to have a “balance problem” in a system that just spits out some integer at the end, than if the player’s goal is a binary win/loss. Maybe the score will be a few points higher because some strategy or component is too strong, but who cares?

Category #3 – “Score Test Systems”

These are systems that do have a binary win/loss outcome, but wherein the outcome is calculated using score. So, there is some score threshold

These are quite common in multiplayer games. Pretty much every single popular sport—football, baseball, soccer, hockey, you name it—uses this method. They are also equally common in designer boardgames, particularly in Eurogames where “victory points” determine the winner (Puerto Rico, Agricola, Through the Desert, etc). Also, notably, Go.

In single player games, you very rarely see this model, however. Civilization counts here because one of the victory conditions is to reach the end of play (some specific year like 2100 or something) with the highest overall score. With Auro: A Monster-Bumping Adventure, I have tried to really hone in on this idea, and I built a whole single-player Elo system making sure that no matter where the player is at skill wise, they get a match that is balanced to their level.

Auro: A Monster-Bumping Adventure

More on Score Test Systems

For the past few years, I sort of accepted the idea that Score Test Systems are basically the optimal design pattern for strategy games. It was only in the past year or so that it started to dawn on me that there are issues there and that we might need to move away from score systems in general in strategy game design.

But first, let me explain why I thought (and still think) that of the three listed systems, score test systems are the best. I will do so by demonstrating the problems with Category 1 and Category 2.

Category 1, completion systems, are quite obviously incompatible with strategy game design. Strategy games are inherently about the pursuit of mastery, and should be deep enough to be played many times. While ultimately, even strategy games can technically be “completed” through “full mastery” (or even close-to-full mastery), that’s not their design intent.

Category 2, high score systems, are a bit more interesting. There are a lot of practical problems with high score systems, such as the problem of ever-expanding match length in Tetris or Rogue. Many of these issues, including that one, can be overcome. But the fundamental problem with high score systems which cannot be overcome is that they are not even contests. Using my system of interactive forms, a videogame that uses a high score systems is a toy, not a game. But let’s talk about what that actually means and why it matters.

Winning and Losing

A strategy game is an interactive system that has some kind of goal. That’s got to be the most uncontroversial way to talk about what a strategy game is that I can possibly come up with; probably literally everyone would agree with that statement.

Let’s get a little bit more granular. In my system of forms, I consider a game (strategy game) to be a type of contest. That means that you are pursuing a goal and being tested on whether or not you meet that goal. You either pass, or fail to pass that test, by meeting, or failing to meet that goal.

You might ask, why is this “testing” component important? Why can’t we just give the player a goal, but then not necessarily have the testing aspect? For instance, you could (and most high score systems do) have a un-testable goal like “get a high score” or “survive as long as you can”. These “goals” ask you to maximize some value generally, without any sort of “check” on the other end.

On a practical level, the response to this would sound like: well, at what point is a score considered “high”? How long do I have to survive before it qualifies as “as long as I could”? If I survived for one second, was that as long as I could? If I survived for 10 hours, was that as long as I could? At no point does the player get any feedback with regards to the goal.

It is undeniable that human beings can follow a general command to “maximize” something, but this is really more of an exploratory “finding of the edges of the system”—a toy interaction—than it is any kind of test. I would call this something like a gameplay guideline or a suggestion, rather than a goal.

While it may meet some definitions of the word “goal”, in terms of how we use the word interactive systems generally, it really doesn’t make sense to say that a general command to maximize something qualifies as a goal, because of the lack of a “test” or “check” aspect. Even completion-based systems have a clear, enforceable, detectable state where you either have or have-not completed the thing. These are more of a test than a toy (and indeed, puzzles add a “goal” to toys in my interactive forms).

In short: high score systems do not have a goal, and they can not be strategy games, contests, or even puzzles. They are formally, and in practice, toys, even if they may have some of the other apparent trappings of strategy games.

Why is the “Test” Important?

Okay, so I’m calling them “toys”, but so what? A better question might be, why do we care? Why do we care that we are “testing” the player rather than just giving them a general gameplay guideline?

Well, firstly I should say that there is a place in the world for sandboxes, simulators, and various kinds of toys. I am not saying “don’t make toys”. What I am saying is that toys are distinct from strategy games, as a form, and if you’re trying to make strategy games but using a high score system (which happens quite often), you’re undermining your strategy game massively. You’re making a toy, and if you knew it, you could make it a much better toy, free from the kind of restrictive, careful “balance” that strategy game-design thinking tends to push you towards.

But why should we preserve the idea of a kind of system that is based around a kind of test? What is the value of the “failure” and “success” states? I think people on the one hand take these things for granted, especially when it comes to multiplayer games (largely for social, and not game design reasons). On the other hand, I think they find these qualities mostly or totally unnecessary for a single-player game. I mean, who cares if you won in a single-player game, right?

I don’t draw a big distinction between single player and multi-player when it comes to strategy games. (I’ve written before, actually, about how I think single player is actually ideal for strategy games.) In either case, you have a player making inputs in pursuit of a specific goal. The fact that the goal is a specific, enforceable thing means that the player can build strategy that (hopefully) leads to it. Strategy is impossible without a binary goal.

A point of clarification: are games like football or Go not strategy games, since they use a high score? Technically, these multiplayer score based games are score-tests, not high-score. They do have a clear, binary goal you're going for: more than the opponent.

Strategy

We say “strategy” a lot, but it might be good to really take a hard look at what it actually is, so that we can figure out what it also is not.

In a weightlifting contest or a 100 yard dash, I think it’s fair to say that there is not a lot of “strategy” going on. I’ve had arguments about this from people who say “actually there’s a LOT of strategy”, and they go on to point out some tiny little fringe aspect that involves strategy. Okay, yeah, for any task there will always be different ways of achieving the task. But when we talk about “strategy” as in “strategy games”, I think it’s fair to say that the kinds of different strategies employed in these contests don’t really register.

In fact, if you are designing a contest, you make attempts to reduce the amount of “strategizing” possible. In an arm-wrestling match, there are lots of requirements about how you can sit, where your other arm must be, and various other regulations that ensure that strategy plays as diminished a role as possible. If we wanted more strategy in an arm wrestling match, we could have the players standing, allowed to use the other hand any way they want, maybe add some symbols on the ground that mean different things, and so on.

Generally, the strategy in an arm-wrestling match is “use all your arm power to push the other guy’s arm down”. There are a number of ways this is distinct from strategy-game-strategy, but the most important one for the purposes of this article is the quality of sacrifice.

Strategy in strategy games almost always involves doing things in an indirect way. It’s not just “do X”, it’s “do Y, which will allow me to do Z, which will allow me to do X”. Usually in these kinds of cases, steps like Y and Z are a sacrifice, or an investment. You’re spending some resources now for a benefit later. Most possible investments are risky; you don’t know the solution to the game or what’s coming, so your invest may not pay off when or how you expect it to.

Knowing the structure of the match (how long, roughly it will be) and having a vision of the end goal (me reaching the target) allow the player to build a plan that involves those investments or sacrifices and leads to victory (hopefully). It allows the player to use strategic long arcs.

So let’s go back to our “maximize your points” idea, where you don’t have a binary goal. Now, how do you build strategy? There are two options:

You choose some number of points to “go for”. In this case, yo