Originally posted at Wayward Strategist

Strategy games, in some ways, are all about limitations. You have limited resources to spend on units and structures at any given time, limited time to react to enemy attacks and tactics, limited attention and reaction speed to manage as you try to eke the most out of your limited supply of units, each with its own constrained functionality.

There is a huge element of skill in strategy games which revolves around mitigating your limitations: ramping up your economy quickly to build (or rebuild) as large an army as quickly as you can (or on striking with an unexpectedly quick army), maximizing your efficiency in combat so that each unit does as much damage as possible to the enemy, paying for itself multiple times and forcing your enemy into a resource deficit so they need to spend resources on rebuilding while you spend them on getting farther ahead. Pure, brual efficiency is a core watchword of RTS, and generally centers around dealing as much damage as possible as quickly and with the least damage and cost to yourself that you can manage.

This is fine, this is well and good, and this is how the game (no matter if it's StarCraft or Age of Empires or Command and Conquer or a hypothetical My Little Pony RTS) is played.

But as the genre has matured, designers have experimented with different types of efficiency. Brute forcing DPS can only get you so far, you see. We'll talk about that, it's important to the conversation.

So, bottom line, what is this article about? What is the point I'm trying to articulate? First, it's that strategy games are best when they include roughly 3 or 4 somewhat independent systems for players to pursue success. And second, that at least some of these systems should provide temporary or recoverable advantages for a player over another. And how giving units ammunition can help with all this.

Binary Is Bad: Gradations Keep Things Interesting

Tooth and Tail, while it has a lot to recommend, tends to have really binary combat outcomes which leads to few quick, explosive battles that decide the game in one fell swoop. This happens in Grey Goo as well, where resource efficiency is often the primary determining factor in match outcome.

Tooth and Tail, while it has a lot to recommend, tends to have really binary combat outcomes which leads to few quick, explosive battles that decide the game in one fell swoop. This happens in Grey Goo as well, where resource efficiency is often the primary determining factor in match outcome.

Fundamentally, I see strategy game design as a delicate balance between 3 primary and somewhat oppositional driving mindets. First, quality RTS design dictates that every system in the game should provide players increasing incremental benefits for skillful handling: the more attention and control you execute on a system, the more you should benefit from it, even though there may be decreasing returns from doing so. Some examples of this include mineral line management in StarCraft 2 including knowing when to expand and some of the little tricks you can pull to eke a slightly higher income out of mineral mining in the early game, Marine splitting to counter Banelings, or strategically selling structures in C&C games. Most combat 'micro' falls into this category, though economics management is important here as well.

Secondly, strategy games are most interesting when they present multiple success and failure states for any given action. If combat encounters are prone to ending with one player's force entirely decimated while the other player has a substantial army left, the game will mostly likely feature many situations where matches are decided after a very few encounters: this is common in StarCraft 2 matches, where a single successful attack can and often does irrevocably decide the match. Tooth and Tail features an even more binary system, leaving a player almost without options or recourse if their opponent gets solidly ahead of them in production or income, especially in the early game.

While WarCraft 3's battles can be strongly decisive, its supporting systems such as worker protection mechanisms, hero leveling and mana pools, and the difficulty of forcing combat encounters to promote tactical combat encounters with a wide variety of outcome states

While WarCraft 3's battles can be strongly decisive, its supporting systems such as worker protection mechanisms, hero leveling and mana pools, and the difficulty of forcing combat encounters to promote tactical combat encounters with a wide variety of outcome states

Creating situations where combat is able to resolve in a partially successful or partially unsuccessful state, allowing players to avoid total and catastrophic failure across the broadest subset of combat and harass encounters, allows the game to continue and a player who might have been temporarily set at a disadvantage through sloppy play or a momentary inattention to redeem themselves, while still putting the player with the better performance at the advantage. For instance, in the Company of Heroes and Dawn of War games, being able to retreat squads back to your base allows you to retain combat ability despite the loss of whatever point of ground those units were striving to hold or gain.

Or in WarCraft 3, where unit health pools tend to be large enough to allow constant poke-and-prodding while players jockey for the stun or body block that allows them to whittle away their opponent's army. Or, to also use WarCraft 3 as an example, where each faction has options regarding base defense: Burrows for Orcs, Ancients for Night Elves, that allow a player to minimize their losses while their army runs or Town Portals back to defend their buildings and units.

There can be tremendous nuance in these systems: in Relic's retreat mechanic, knowing where and when to retreat, as well as knowing the fleeing squad's path back to base is critical: it is possible for a player line up a high damage squads along retreat paths to snipe fleeing units, making the system still one where skill is involved.

Taking A Look At Skill

Relic victories and Wonders in games like Dawn of War and Age of Empires allow different types of play to be successful and different types of efficiency to drive a win than in "destroy your opponent's stuff" games like StarCraft. And the extra method to drive a win can enable a player who's fallen behind the opportunity to still try and pull off success along a different avenue.

Relic victories and Wonders in games like Dawn of War and Age of Empires allow different types of play to be successful and different types of efficiency to drive a win than in "destroy your opponent's stuff" games like StarCraft. And the extra method to drive a win can enable a player who's fallen behind the opportunity to still try and pull off success along a different avenue.

Why does this matter? Clearly, in strategy games, the player who is better should win, so why prolong the agony of the other player's defeat? Why give the worse player more chances to accidentally (or via dumb luck) defeat their superior opponent? This comes down to the nature, and the fun, of strategy games. It comes down to creating interesting competitive experieinces for people, and participating in those experiences yourself.

Fundamentally and frankly, I'm basing this assessment on overall game feel and what I see as an effort to keep matches fun and interesting for as long as possible and across the widest possible subset of matches; I see specific mechanical paths towards making that a reality. Please understand that I am advocating for a personal preference in game design and that I'm pushing for a slightly different definition of 'skillful play' and even of 'winning' than you might see in most strategy games. What I'm looking to do is advocate for game designs that allow players to feel like they're still able to act and participate in the game even when they're losing. I am advocating for empowering players, and trying to acknowledge the drawbacks of my recommendations as I put them forward.

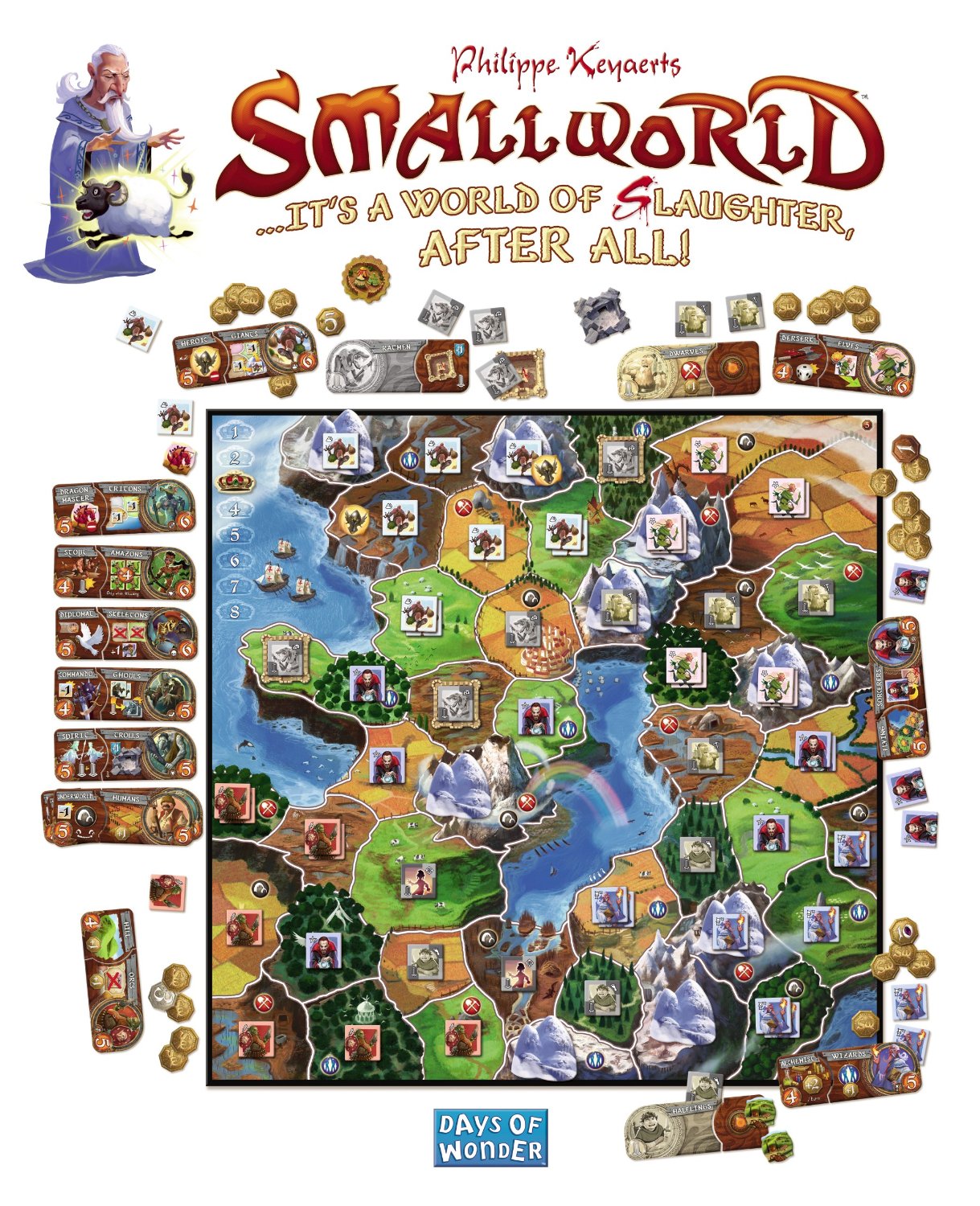

In strategy games, as in all competitive games, the player with the better strategy and execution deserves to win. But consider a game like SmallWorld, or like tabletop Warhammer 40,000, where the winner is almost always determined by the end state of the game upon its end condition being met, or in Dawn of War with its Relic win, or in Age of Empires where one can achieve an economic and defensive victory via a Wonder, allows win states at least somewhat independent of either player's overall ability to wage war.

The board game SmallWorld, where victory is determined by total funds amongst all the races you controlled during the game's duration. I'm not a huge board game aficionado, but I've had tons of fun with it[

The board game SmallWorld, where victory is determined by total funds amongst all the races you controlled during the game's duration. I'm not a huge board game aficionado, but I've had tons of fun with it[

Skill-based victory is still skill-based victory. There will always be situations in skill-based competitive games where a crushing victory happens, and that's fine and good. What I'm interested in is strategy games which force the better player to have more consistency in establishing dominance, or in having them win while still allowing the losing player access to all or most of their ability to act on the game. What I am also interested in is systems which encourage players to master and demonstrate skill along multiple avenues in order to achieve success.

Multiple Avenues For Success

Despite my appreciation for many of its mechanics, victory in Steel Division is still highly correlated with your ability to keep your army units alive, with few 'levers' to pull to reverse your fortune if your opponent gains the lead in this regarw

Despite my appreciation for many of its mechanics, victory in Steel Division is still highly correlated with your ability to keep your army units alive, with few 'levers' to pull to reverse your fortune if your opponent gains the lead in this regarw

It is my contention that competitive games are most interesting when all players feel like they have some option to continue and succeed for as long as possible. Clearly, there will come a moment when success, and more importantly the feeling of being able to succeed, will be lost for one player or team, but that moment can and should be pushed back as much as possible. When a player feels they are unable to act on the game in meaningful ways, when it feels like they have no options or control, they are frustrated.

And just what does this have to do with ammo, mana, morale, and other similar systems in strategy games? I'm getting to that. Bear with me.

Above, I have tried to lay out my position that a state of homeostasis or equilibrium (analogous to the midgame phase of most RTS) creates the most interesting game state for both players, and that tipping the game from this state towards a win should require, in most cases, repeated successes by a dominant player in order to insure a win. Further, this should be facilitated via systems like:

Multiple systems that drive player success, each being at least partially independent from one another. This allows players to still go for a win if their opponent hampers their effectiveness in another area. An easy example is in StarCraft 2 early to mid-game, when players can choose a combination of economic expansion, army size, harassment options, or tech to attempt to overpower their opponent.

Win conditions that are divorced from a player's ability to play the game. For instance, in StarCraft you win by removing your opponent's ability to fight back, while in Dawn of War 2 you win by reducing your opponent's Victory Point total to 0 by holding more VPs than your opponent for longer.

Creating systems where players can recoup or reatreat from a loss, or where combat outcomes tend to be less binary. One example is the Retreat mechanic found in the Dawn of War and Company of Heroes games.

So here's where we get to efficiency. The fewer vectors for success there are, the more success is driven by efficiency along those vectors. In StarCraft 2, for example: the core resources of Minerals and Vespene are the primary mechanism for expanding the player's options and acting on the game state, and expanding a player's income with both of these is vitally important. But the number and position of each unit factory type also affects a player's ability to produce units, and having too many or too few of a given factory type can itself cause problems. Likewise, while upgrades in StarCraft can sometimes be subtle, sometimes having additional armor or damage can tip a type in your favor: overall, managing all of these things provides each player with a number of interesting choices for how to develop and implement their strategy... in ways that often are completely undone by players' (especially those in Platinum league and below) to deathball their massive armies around, where victory often devolves into who can kill the other player's army more often and rebuild theirs more often.

While a large part of combat in Company of Heroes 2 still comes down to the 'gordian knot' of DPS, systems like Suppression, vehicle damage states, smoke, and the interlocking infantry counter system gives players plenty of ways to derail an opponent, and widely spaced control points make it possible to attempt to strike where your opponent might be weaker

While a large part of combat in Company of Heroes 2 still comes down to the 'gordian knot' of DPS, systems like Suppression, vehicle damage states, smoke, and the interlocking infantry counter system gives players plenty of ways to derail an opponent, and widely spaced control points make it possible to attempt to strike where your opponent might be weaker

So all of those interesting choices, except at the higher levels of play, can definitely be bypassed or subsumed under the weight of income and DPS. Obviously, this is a bit reductive: abilities, positioning, and other tactical and strategic considerations (force field, observers, roots, psy storm, etc) can and do come into play.

Breaking it down, StarCraft 2 has a lot of factors in play, many of which are at least partially avoidable or ignorable, until high levels of play. I mean, it's a pretty flexible and robust system. There's a reason it's so popular.

Let's contrast this with Tooth and Tail, though. In Tooth and Tail, there is only one resource: food. And it's used to build structures, build units, build farms (economy) and take new bases/territory. So ultimately, everything in Tooth and Tail comes down to food. And that's the point of the game. It's incredibly focused, and I think that's praiseworthy. But in multiplayer, it can be merciless. Once things start going badly for you in Tooth and Tail, especially in that pernicious early game before you've expanded, losing, well, anything can put you into the kind of tailspin that happens in Zerg v Zerg matches in StarCraft 2: that is, you'll never be able to catch up economically. Economy growth curves make it increasingly statistically likely that food 'wasted' on units you have to rebuild will allow your opponent to get that much farther ahead, have more resources to spend on units, and so on rolls the snowball.

In Tooth and Tail, it all comes down to food.

In Tooth and Tail, it all comes down to food.

Combat in Tooth and Tail is much more linear than StarCraft 2, since you basically only have the 'levers' of combat skill, unit choice/positioning (there is an interesting element here where you're able to choose between lower level and higher level/more powerful units, but that strongly correlates to income), and income to pull, and they've been somewhat dulled by passing all orders through the imprecise sieve of your Leader unit.

To further belabor the point, Company of Heroes 2 gives players a good variety of levers to pull: Manpower is largely fixed income, which inflates or decreases based on how many extant units you have. Fuel is scarce and punishes poor play with vehicle units. Munitions start out scarce but become plentiful in the mid-to-late game, where armies are larger and dealing wide damage with Napalm is a little easier to come back from. Add to this a really dynamic infantry combat system with cover, morale and the suppression system, smoke and grenades and indirect fire weapons. This expands to include light vehicles, which interact differently with indirect fire and MG weapons and regular infantry, then expands again with heavier vehicles and AT guns, and expands again in the late game with super-heavy tanks. Each phase of the game increases the number and nuance of interactions, while expanding Munitions income allows more consistent use of game-changing abilities.

So, in Company of Heroes 2 you have those 3 resources (4, really, if you count VPs as a resource), each with its own purpose, that players can spend in various ways, then there's the interlocking unit dynamics that has little, but some, leeway built into it - like how