This is an updated version of a post from 2013 by the same title. You can read more on my blog Game Make World.

From April 2010 to May 2011, I had the opportunity to study manga (Japanese comics) and video game design at Kyoto Seika University, an art school in Japan. In total, I lived, worked, and studied in Japan for about four years, and here I would like to share what I learned about Japanese developers' approach to game design.

It all started in high school when a friend introduced me to anime through Studio Ghibli's Princess Mononoke. The characters and creatures were unlike anything I'd seen before, and soon I was borrowing more. From there I started playing Japanese video games, especially Super Nintendo-era role-playing games.

The first one I happened to play, chosen at random, was the oddly titled Chrono Trigger. Little did I know I was picking up one of the most revered games of all time, and, of course, I loved it. Similar to my response to Ghibli's movies, I was enchanted by the amount of imagination I saw in Japanese RPGs.

An Overlooked Treasure

Eventually I stumbled upon Paladin's Quest, a lesser-known SNES RPG released in the US in 1993. I almost skipped the game entirely due to its generic name; I don't know how translators settled on it since the game has nothing to do with paladins. In Japan it goes by the exciting and mysterious Lennus: Memory of the Ancient Machine.

Paladin's Quest turned out to be, in my opinion, the most original and memorable game from an era that was already brimming with new ideas. The pastel colors and simple visual style turned off many players, but their novelty, together with the haunting music, alien plant-life, and unusual control scheme, only added to the appeal for me.

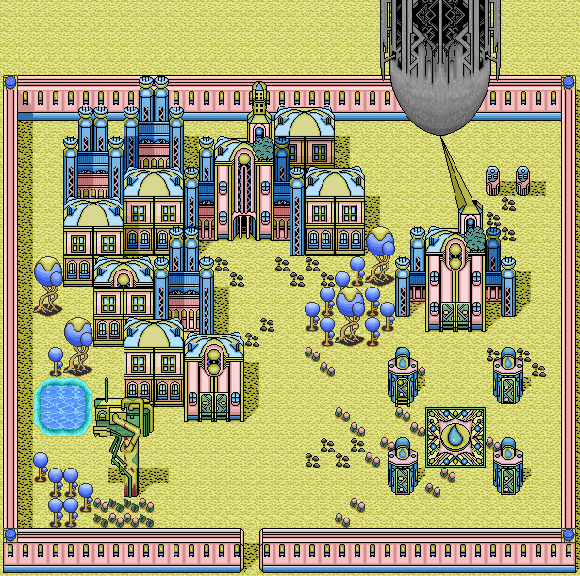

"The Magic School," the first area of Paladin's Quest

"The Magic School," the first area of Paladin's Quest

For the Love of the Game

When I found out that Paladin's Quest had a sequel, Lennus II: The Apostles of the Seals, I was eager to play; however, the game had never been released in English, and with zero knowledge of Japanese, I couldn't even make my way out of the first area.

That's why I enrolled in an "Intensive Japanese" class in college that culminated in a four-week trip to Kyoto Seika University. At the time, Kyoto Seika had just made news for being the first school in Japan to offer a major in manga.

The experiences I had there led me to transfer to Stanford University to major in East Asian Studies and continue studying Japanese. After graduating I moved to Japan to teach English with the Japan Exchange Teaching (JET) Program.

That was when I discovered the blog of Hidenori Shibao, the director of the Lennus series, who also worked on Legend of Legaia, a PlayStation RPG. I commented on his blog, and we ended up exchanging a few emails about the Lennus series and game design in general.

Back To Kyoto Seika

After two years with JET, I wanted to return to what drew me to Japan in the first place: popular culture like video games and anime. I had always loved drawing, and I remembered Kyoto Seika and its manga program from my study abroad trip. That's how I ended up going back in 2010 as a research student in the Story Manga Department. (As a "research student" I took classes like a regular student but didn't get any grades or diploma.)

Although Japanese schools tend to be strict about taking classes outside your department, I was able to attend some lectures in a game design class with Kenichi Nishi, the director of the cult-hit Chibi-Robo! (He was involved in Chrono Trigger as a "field planner," too.) Nishi walked us through development from idea to execution, and students formed groups to create their own games over the course of the semester.

Through all of this, I learned a lot about the Japanese approach to creating popular culture like manga and video games, but I want to focus on two major points: Japanese-style characters and their function in video games, and sekaikan, a term used frequently in reference to video games and other media.

Japanese Characters: More than Just "Cute"

Anyone who's been to Japan can tell you that cute characters appear everywhere: billboards, TV, clothes, trains, food (and not just the packaging, but often the food inside, too) -- anywhere you can imagine.

You can even find them in situations that in America might be considered slightly inappropriate, such as a flyer I saw that proclaimed something along the lines of "Let's reduce the number of suicides!" with a boy and a cute green creature raising their fists in smiling determination.

In Japan, the huge demand for and production of characters constitutes what is essentially a character industry; video game, anime, manga, and merchandise companies work together in close coordination to create spin-offs, crossovers, and various products based around popular characters. This is referred to as "media mix," and through these media mix collaborations, a character from a successful manga series, for example, can end up bringing in far more money than what's genrated by sales of the original manga itself.

The Pokémon Train

The Pokémon Train

Hello Kitty rice balls

At Kyoto Seika, my classmates were very much aware that creating popular characters was a crucial part of the manga-making process, and, as you can imagine, skilled character designers in Japan are highly valued. There are artists like Kosuke Fujishima of the Tales series of RPGs and Metal Gear's Yoji Shinkawa (a Kyoto Seika alumnus whose iconic art is seen to the left), who have achieved great fame and recognition thanks in large part to their work designing characters. Artists such as these have their work featured in exhibitions, and can sell expensive art books of their sketches and designs.

At Kyoto Seika, my classmates were very much aware that creating popular characters was a crucial part of the manga-making process, and, as you can imagine, skilled character designers in Japan are highly valued. There are artists like Kosuke Fujishima of the Tales series of RPGs and Metal Gear's Yoji Shinkawa (a Kyoto Seika alumnus whose iconic art is seen to the left), who have achieved great fame and recognition thanks in large part to their work designing characters. Artists such as these have their work featured in exhibitions, and can sell expensive art books of their sketches and designs.

The Making of Japanese Characters

Some people may be familiar with the term kawaii, which is usually rendered in English as "cute." However, I think it is not as simple as just being "cute"; my understanding of kawaii characters is that they are expressive, endearing, and easy-to-read, with large heads and eyes, simple, colorful designs, and exaggerated emotional reactions.

A term less well known outside Japan is sonzaikan, which literally translates to "the feeling that something exists." In terms of characters, it means that they seem real -- not necessarily that they are just like real people with complex personalities, but more that they feel full of life and provoke an emotional response from the viewer.

But in practice, how do designers make these kinds of characters? Ian Condry, a cultural anthropologist and professor at MIT, describes one example in his paper, Anime Creativity: Characters and Premises in the Quest for Cool Japan. There, he interviews m&k, the design team who created the characters for a popular animated show called Dekoboko and Friends.

[T]hey developed the characters by "auditioning" about 60 of them, that is, drawing up a wide range and selecting from them. "We avoided average characters, and aimed instead for those who were in some way unbalanced," he explained... The creators also didn't start with the visual image of the character, but instead thought in terms of a character's distinctive flavor (mochiaji) or special skill (tokugi)... "[T]he personality (kyara) precedes the character itself, evoking the feeling of some kind of existence (sonzaikan) or life force (seimeikan)"... When m&k selected characters from among the many they auditioned, they emphasized the extreme: one character is extremely shy, another extremely speedy, another is an elegant older woman who sings traditional sounding songs, another is so big he can't fit through the door.

In other words, each character is defined by a simple concept, which in turn determines both their behavior and appearance. The result is that, though simplistic, each character feels likable and real.

Dekoboko and Friends

Dekoboko and Friends

What Characters Are: Characters in Games

In his game design blog "What Games Are," Tadhg Kelly explains characters' role and function in video games, and his description seems to me to be especially true in relation to Japanese character.

First, it helps to understand his view on the role of story in video games. In his post On Player Characters and Self Expression, Kelly explains what he calls "storysense":

"Storysense" is an approach to narrative which relies on the creation of an interesting world, a discoverable set of threads and bits of story, a minimalist approach to goal direction, but dispenses with dramatic plot and character development. It treats story as a backing track to the play of the game, and so the player can participate or not as he likes. There is no time given over to extrinsically rewarding the player for being in-character, and the only rewards are literal -- just as the game is. There is no elaborate characterization, no attempt to insert unnecessary meaning, and no emoting at the player to try and make him or her feel.

That's why, he explains in Character Establishment, characters in games don't need traditional development through a story:

Establishing character is not the same thing as character development. Character development in a dramatic arc is a long and complex process, but in a game it's completely at odds with what a world needs to achieve. The art of establishing characters is conveying an impression of who they are in totality, because they are just a part of a portrait.

A game character needs to be established with a light touch, so that it's the player's choice to like or loathe at their own pace. Take that away, or foist exposition on the player, and intended feelings of sympathy quickly turn to antipathy or boredom.

As he sums it up in his post on Character Development, "the world is what develops and characters are (for the most part) just resources within it."

Japanese characters, with their impression of being real (sonzaikan), and simple but engaging personalities (like the Dekoboko characters), seem well-suited for this kind of role. More so than physically and emotionally realistic characters, simplified and stylized kawaii characters help bring the gameworld to life for the "art brain" without distracting the "play brain."

Taking Care of Characters

Given characters' importance in terms of gameplay and companies' success, it should come as no surprise that great care is taken in handling famous characters. I was personally surprised, however, to discover that there is an entire company, called Warpstar, devoted to managing Kirby. Warpstar collaborated with HAL Laboratory, for example, in the making of Kirby's Epic Yarn for the Wii, and in that case, designers spent an incredible three months perfecting Kirby's appearance.

This careful attention to characters can also be seen in interviews with the team who made Zelda: Skyward Sword. The designers discuss working to make even the enemies kawaii, to give them "a touch of humanity" that makes you like them even as you defeat them.