In honor of the 13th anniversary of the release of the one of the best-selling PC games of all time, we present this classic postmortem, which first appeared in the January 2005 issue of Game Developer magazine. This in-depth look at what went right and what went wrong during development was written by Lucy Bradshaw with contributions from fellow Maxis devs Matt Brown, Tim LeTouneau, and Paul Boyle.

Sequels to successful games may seem obvious—maybe even too obvious. And with The Sims, we at Maxis had a lot of content to work with and many leaps in technology to take advantage of since the first game was shipped back in 2000.

Even so, sequels pose a unique challenge. The Sims 2 team had to understand what led to the success of the original and devise a way to evolve (and ultimately how to innovate) while juggling colossal expectations from fans, critics, and the company.

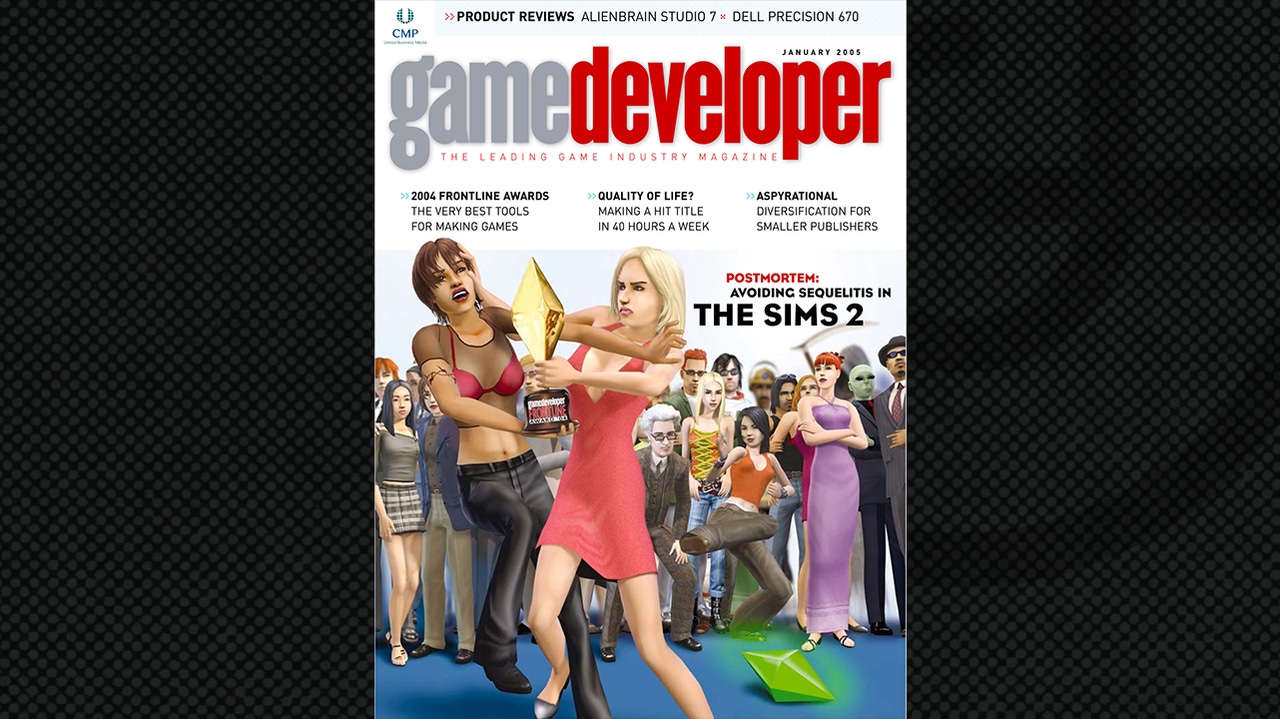

Image via Game Developer Magazine, January 2005.

What went right

1. Prototyping

Maxis has always been a major proponent of rapid prototyping when kicking off a new game. We used early prototypes to resolve look and feel issues, to help understand the key emotional connection, and most importantly, to test out the new gameplay concepts. Building these prototypes during the concept and pre-production phases instead of during the full steam production phase just makes sense.

Many of these prototypes significantly affected the final design of the game. The look-and-feel prototype, for example, established how The Sims look, particularly in the adult and teen years, and set the tone for the new 3D environments.

The HeadToy prototype helped evolve the Create A Sim tool. Later in the project, the "aspiration, wants, and fears" prototype guided the way we created the new gameplay. All of these prototypes were done as separate applications, using existing tools, such as Maya and .Net, and executed by one or two engineers or artists.

Our key to success is being rapid, staying focused on what we're trying to solve and moving quickly. We aim to show progress and iterate frequently. If someone working on a prototype has not shown us something each day of the week, it's probably going sideways.

Each of these prototypes was different in its implementation. The visual look-and-feel prototype was simply a movie, but it set the bar for the lighting, camera, environment, and characters.

The HeadToy prototype gave us a chance to explore some rather extreme possibilities in the new Sims's appearances. It also inspired Sim DNA, the virtual genes that are passed along to Sim descendants. One of the core design concepts that came out of this stage of the project was that The Sims 2 would grow up in The Sims 2.

The prototype not only nailed the various ages and the creative possibilities, but also validated the Sim DNA concept. This influenced the user interface, changed the way we talked about the game, and ultimately became part of the marketing campaign: "Genes, Dreams & Extremes."

We used the "wants and fears" prototype later in the project, but it was critical in providing the major innovation in regard to player focus and gameplay pacing. The prototype, built by Matt Brown and his team, let the designers and the engineers play through the wants and fears trees and establish the logic involved.

Situational humor helps to create an emotional bond for the player. Image and caption via Game Developer Magazine, January 2005.

2. Understanding the audience

Our challenges in making a sequel to The Sims was to intrigue the currently active players as well as recapture players who had uninstalled long ago. The audience of The Sims has changed rather dramatically since the original—they've evolved from hardcore players to ones who are very casual or new to games all together.

We focused on what we felt were some of the key factors of success in The Sims. We worked with our publishing partners to get a picture of our player base.

We also spent a lot of time on the forums in our website, as well as other fan-sites and bulletin boards. We came to several conclusions. One was on the topic of The Sims: a game about people is something that most folks can connect with.

Other factors that we felt were critical were the creativity, the open-ended nature of the experience, and the sense of irreverent humor. We spent a lot of time brainstorming ways to improve these aspects of the game. We enhanced the creativity by improving the Create A Sim module, refining the building and designing options, and by creating a new means of storytelling via moviemaking.

We bolstered the open-ended nature of the game by keeping the same depth and breadth, and by making the lives of the Sims feel richer through additions to the social landscape. Finally, the key to this audience was the addition of growing Sims and playing through the generations of their families.

We recognized that we needed to attract our previous players through innovation. A major lure for these lapsed Sims players was the move to full 3D. This gave us an instant leg-up on the original, but we also parsed a lot of feedback from reviews, player suggestions, and focus groups.

From these outlets, we heard that players were tired of managing the mundane aspects of their Sims' lives—they wanted a new focus and pacing. Another thing we identified from listening to focus groups and player testimonials is that a great many players had not discovered some of the crazy things that could happen in The Sims and its expansions. Players had simply not put together the right combinations of actions and objects to discover these bits.

We boiled this down to the need for new pacing and rewards as well as a need to refine and maintain the open-ended gameplay. We had to find a better way to guide players and expose them to more of the possibilities that we had created.

The entirety of these observations drove much of our brainstorming about features and rewards, and led to the composition of features that we eventually included.

3. Kleenex testing

Use once, throw away. Kleenex testing, in our vocabulary, means using disposable testers throughout the design process—from alpha to release candidate. The key to fresh feedback is using each tester only once: just like Kleenex. Since so much of our game hinges on players immediately understanding the gameplay and the interface, and that the rewards hit with good pacing, we elicited feedback and acted upon it regularly throughout the development process.

The most important part of Kleenex testing is finding people who can play a game with someone looking over their shoulders and while voicing the thoughts that go through their heads. Not everyone is cut out to be a piece of Kleenex.

We completely iterated the Create A Sim interface three times because of feedback received during Kleenex testing. This testing allowed us to better categorize the steps and make the flow of Sim design more natural and clear to players. There's quite a bit of depth to creating a Sim, and since a Sim's appearance can be very important to the player, this is an area in which we had to supply both complexity and simplicity (ease of use).

4. Custom content and community

At Maxis, we believe that a great deal of the success of The Sims came from the wealth of content and characters created by our user-base and enthusiast communities. When we initially shipped The Sims in February 2000, we had already created and released tools that enabled fans to create Sim skins. We continued to foster this community by adding more tools to a frequently updated and community oriented web site.

When we embarked upon The Sims 2, our philosophy was: If you could see it on the screen, you should be able to customize it. We also wanted to integrate this capability more seamlessly into the game, making it easier for players to manage the content they gathered or created.

We designed the user interface for data management to realize this goal. We also integrated our web site directly into the game through an in-game browser that allows players to download skins or objects and use them immediately.

In addition to this, we continued to keep an open dialog with the fans and webmasters supporting The Sims. We asked their opinions, got their feedback, and even kept up a weekly mailing on the progress of The Sims 2. We maintained this mailing list for a full year before we shipped.

One very successful event was the launch of The Sims 2 Body Shop, our tool for creating The Sims 2 skins. We made this available to the community on the opening day of E3 2004, when we premiered the game on the show floor. We had more than 80,000 skins on the site by the time we shipped the game.

One problem we encountered with this simple-to-use tool, however, was that we made it easy for users to brand the work of others as their own. We built some solutions into the shipping product and web site to make sure the creator identity is seen (if desired) and made sure we created strong community ethics for our site.

Today, the community is thriving, and player-created content made with The Sims 2 Movie Maker is something we are very proud of.

5. SWAT teams

SWATs are small, cross-discipline teams within the larger development team that tackle key features and technical issues. SWATs (some call them pods or cells) helped The Sims 2 team focus on several fronts, thanks to strong leadership in each group responsible for decisions, communication, and tasks, such as pushing for the completion of their team's projects. On a large team such as ours, this requires an essential tactic. These SWATs evolved over the course of the project, coming together and disbanding as their objectives were initiated or met.

We had a neighborhood SWAT, which was responsible for all the visual features in the neighborhood: everything from the on-the-fly creation of house imposters to the landscape and effects. There was also a neighborhood story SWAT, which built all the finished neighborhoods. This team created all the prebuilt content, relationships, and ephemera so players could jump right in and experience the game.

The Create A Sim SWAT was the team that created the workflow and technology behind the Create A Sim module. The Sims 2 Body Shop SWAT shipped a "product" twice during the production of The Sims 2. The Body Shop had to go through Q/A, CQC, localization, and all the other processes a stand-alone product must weather. This was an amazing team of people.

There are more than 11,000 animations in The Sims 2. Image and caption via Game Developer Magazine, January 2005.

One of the most distinctive teams on the project was the believe SWAT. They were saddled with the duty of changing the behavior of our Sims to match the new, more detailed aesthetic.

This team worked together to really put our animation engine, which was designed by David Miller, through its paces. Human beings know how human beings behave.

One of the major challenges we faced in The Sims 2 was matching the motion to the meat. We had to experiment with using the animation engine to its fullest, which extended all the way to adding a breath channel and a very subtle but effective facial movement channel (before we put this in, Sims just looked too noticeably mechanical and creepy—see Steve Theodore's "Uncanny Valley," December 2004).

As for behavior, the challenge was to create new routing, awareness, moods, and personalities which would work autonomously, be eminently interruptible by the player, and provide clear feedback about what was going on with the Sim in question. We knew we had it right when our testers didn't notice it. When we got to that point, we figured we had believable Sims.

There were many other excellent SWAT teams on our project, and they all contributed to the final feature set in ways that could not have occurred without this specific compartmentalization.

What went wrong

1. Noisy feedback

Players need to be able to read how their actions affect the game structure. Feedback, therefore, must be simple and intuitive. The believe SWAT team had to experiment a great deal with the behavior and movements of the new Sims in order strike a successful balance. One of these experiments was a bust, which ate up a lot of time and effort.

We were experimenting with bringing the personality dimensions of each Sim to the forefront by enabling players to affect this area to a greater degree. We experimented with animations and behaviors that were intended to show off the extremes of the five pe

No tags.