Introduction

In recent years, retrospectives of classic games have been well received at GDC, but there have been very few stories about classic game tools. This series of articles will attempt to fill that gap, by interviewing key people who were instrumental in the history of game development tools.

The first three articles in this series have featured John Romero (about the TEd Editor), Tim Sweeney (about the Unreal Editor), and Chris Norden (on tools for the original Deus Ex).

For the fourth article, I am very excited to speak to Dan Amerson, Mike Daly, John Austin, and Tim Preston about the history of the Gamebryo game engine.

Roundtable

John Austin joined NDL – the company that would go on to produce the Gamebryo engine – in 1998, at a time when they had only four customers. He was brought in as VP of engineering to give structure to the team.

Tim Preston joined NDL in 1999, initially working on the Mac port of the engine. After a short stint in particles and animation, he moved over to rendering, and was lead on the DirectX renderers and PC platform.

Dan Amerson joined in 2001. He worked as a Gamecube lead, Xbox 360 lead, and eventually technical director for rendering and runtime.

Mike Daly joined in 2004, right out of college. He met Dan while he was going to NC State. He started off working on exporters, and then worked on the toolchain.

RayTracing a path to the birth of NDL

The story of Gamebryo starts in the early 1980s.

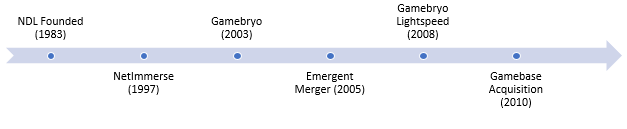

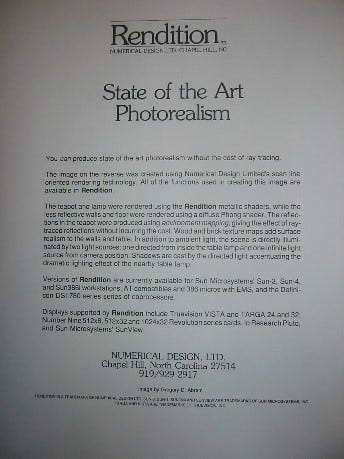

In December of 1983, J. Turner Whitted and Robert Whitton founded Numerical Design Limited, or NDL. The company was based out of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, primarily staffed by grad students from the UNC Computer Graphics program.

Whitted was responsible for introducing recursive ray-tracing to the computer graphics world via a paper that he wrote in 1979, entitled “An improved illumination model for shaded display”.

Turner Whitted and a render from his 1979 paper

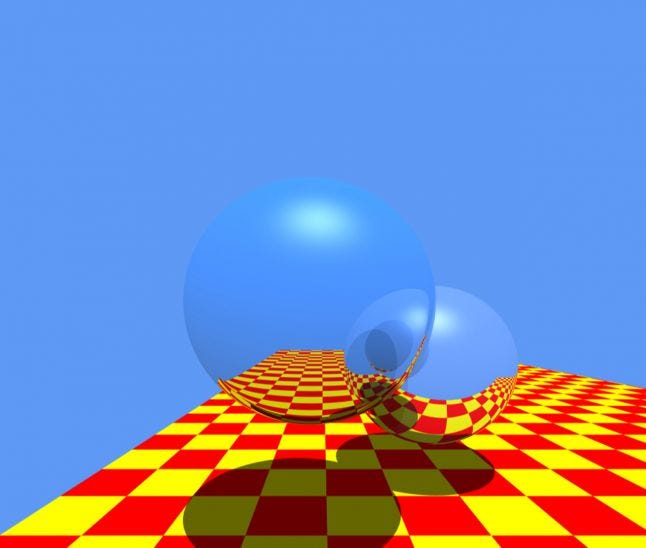

NDL’s first product was an off-line rendering engine called Rendition, and the main customer was AutoCAD. At that time, Autodesk was paying most of the bills.

In the 1990s, the first wave of VR started coming, and Intel had a real-time graphics software called 3D Worlds. They licensed it to NDL and, at the same time, invested in NDL through a convertible note. At that time, the graphics technology was known as NetImmerse.

The first few customers who used the NetImmerse real-time graphics engine were Prince of Persia, released in 1999, and Dark Age of Camelot released in 2001. NetImmerse was only a graphics engine at that time, and so everything else aside from the graphics engine was made by the developers who licensed NetImmerse.

The Bright Age of MMORPGs

Due to the success of Mythic Entertainment’s “Dark Age of Camelot”, NetImmerse started to become associated with real-time MMORPGs, which – with the success of Ultima Online, Everquest, and Asheron’s Call – were very popular at that time.

This is ironic, as NetImmerse was purely a graphics engine, and had nothing to do with the networking code that made massively multiplayer games a reality. In the case of Dark Age of Camelot, Mythic Entertainment wrote all the networking code.

It’s possible that the word “Net” in “NetImmerse” had an influence on this. John says that “we had nothing to do with the multiplayer aspect of [Dark Age of Camelot]. All we were at that point was a graphics engine, but because that game happened to be in that genre, we picked up a bunch of customers in that space.”

Not only was it simply a graphics engine, but there were no editors at that point either. However, NetImmerse did come with a suite of very capable exporters.

We had nothing to do with the multiplayer aspect of [Dark Age of Camelot]. All we were at that point was a graphics engine, but because that game happened to be in that genre, we picked up a bunch of customers in that space

Bringing an exporter to a .NIF fight

NetImmerse used the proprietary NIF file format. NIF files could be created using the exporters that came out of the box. Compared to the competition at the time, the exporters were quite capable. “Our exporters were probably the most fully featured in the industry and they did their best to make sure that what you saw in your 3d tool was exported into the engine”, Dan said.

They also included the ability to mark up your scene with game-specific information, which would allow you to downsize textures, set culling settings, and so on.

One of the factors that contributed to the quality of the exporters was that the team had set up an automated process where the exporters would export assets to PC, Playstation, and Xbox overnight, and then compare the results to test images to make sure that they kept their fidelity as closely as possible.

It’s worth noting how unusual it was to have powerful exporters out of the box in those days. There was no common interchange format, and DCC tools – such as 3ds max, Maya, and Softimage – were not architected to have exporters. “It was a non-trivial task to get data out of them at that time”, Mike added.

The exporters were very appealing to a large number of customers. Being able to use the DCC tools that everyone was already familiar with was one of the strong selling points of NetImmerse

It was worth it, though, because the exporters were very appealing to a large number of customers. Being able to use the DCC tools that everyone was already familiar with was one of the strong selling points of NetImmerse, and that continued to be the case for many years.

ABC, Always Backwards Compatible

Backwards compatibility was also an important consideration for people working on NetImmerse. It did take some people time to come around to the idea, though.

“When I was the young guy in the company, I was the one arguing that we need to just ditch the backwards compatibility and have people re-export.” Dan said. “Then, I got on the ‘we have to be backwards compatible’ train because Tim convinced me that we have to, then Mike joined the company he was like ‘can we just make them backwards compatible?’ [laughs]”

A lot of energy was spent making everything backwards compatible. As a testament to the work that the team put into it, some NIF files from NetImmerse 1 could still be loaded into Gamebryo Lightspeed, over 10 years later.

It didn’t always work, though. Tim said, “We did break it once somewhere on NetImmerse 2 and that made [Mythic Entertainment] very unhappy, because they had a whole bunch of assets that they had already exported, and they didn’t have the master files for them anymore. They went back and wrote a NIF converter for that specifically. After that, we would deprecate features now and again, but we would always make sure that there was a NIF converter”

Dan is fourth from the left, Tim is seventh from the left, and John is third from the right

From Everything-Immerse to Gamebryo

One of the first real tools that was created was an animation tool. It was used to apply animations to different characters, to chain animations together, or even to morph animations from one to another. The other was a viewer for previewing .NIF files that had been exported. “Those were the only real tools we had for a long time”, Mike said.

It became a running joke internally that everything had the suffix “-immerse”: The exporters were called “MaxImmerse” and “MayaImmerse”. The Animation tool was called “AnImmerse”. There were even some other internal tools, such as an Excel plugin called “BizImmerse” and a tool for golf course visualization called “GolfImmerse”.

Most of the team didn’t like the name NetImmerse, or how the word “-immerse” was appended to all the product names. So, they started talking about a re-brand. They discussed names such as Typhoon or Hurricane.

Finally in 2003, with the assistance of the marketing firm CapStrat and Bennett Hazlip, the name “Gamebryo” was chosen. The NetImmerse engine was renamed to Gamebryo, though – under the hood – it was still the same rendering pipeline, runtime, exporters, as well as animation and viewer tools.