This blog was originally published on my website. It is the essay version of a talk I gave at the GDC 2018 Narrative Summit. You can view the video recording here (subscription required).

My entire career I have been in and around simulations, the military and war.

I started off as an amateur modder for Bohemia Interactive’s first game, Operation Flashpoint. I then got a job at their new Australian studio where we started making Virtual Battlespace 2 (VBS2). That product completely changed the simulations industry and established games as serious training tools for the military. I moved to Orlando when we first opened an office there.

At the time I was also in the USMC reserve. I left Bohemia and volunteered for a 7 month deployment to Afghanistan in 2011 as a Civil Affairs specialist. After that I went back to Afghanistan for a year as a civilian trainer working on a DARPA project that made smartphone apps for soldiers to use in combat. I returned to Bohemia Interactive Simulations (BISim) in 2013, now in their Prague office, and have been there ever since.

Expectation vs Reality

Over the years I’ve found a huge disconnect between the reality of war, and how it is portrayed in TV, films, and games. Here’s an example of what it can feel like talking to civilians about war:

A typical conversation about war with a civilian

In general people appreciate the military, but they have an extremely shallow understanding of what exactly it does, and what war is like.

In 2011 I was deployed to Sangin district, Afghanistan. For years this was the bloodiest battleground of the entire war, with units taking 10-20% casualties during their tours there. It was basically a low-density minefield that we were walking in every day. We would walk single file — following the footprints of the guy in front of you–because if you stepped off the path where someone else had walked you might step on an IED and get blown up. Or sometimes one guy would step over an IED, and the next guy would step a little different and get blown up. Before I got there, the insurgents would set up ambushes where they put IEDs behind good cover. Then when they shot at the Marines, the Marines would run to cover, lay down on an IED and get blown up. By the time I arrived, we were told to just squat down in place and shoot back if we took enemy fire.

So from what I just described, you might imagine a typical day looked something like this:

A typical day in Afghanistan?

In fact, a typical day usually looked more like this:

A typical day in Afghanistan

A typical day of walking around in a minefield, talking to farmers about their donkeys, or their house that got blown up. This is what modern warfare looks like today. You know what I heard one of the younger Marines say in the middle of this deployment?

“This isn’t what I expected. I thought I’d be doing hero shit like in Call of Duty.”

What you may not realize is that your work as writers and game creators really matters. It helps set society’s expectation about war and the military. That’s because humans are built to learn through stories and emotions and play. You are the best teachers. So what lessons are you teaching?

Let’s write about… relationships!

Let’s say we want to write a movie about relationships. This is something most people have first-hand experience with. We might brainstorm all the themes related to this topic, like dating, marriage, friendship, love, romance, heartbreak, etc. We have a massive canvas of narrative themes we could choose from for our writing.

Now what if some studio executive came in and said, “we did some market research, and found out what excites our audience the most. So I want you to only focus on this one theme: sex”.

What kind of movie would we end up writing?

Obviously that’s porn. It may be exciting but it’s a bit shallow. And although relationships can include sex, nobody would really say that porn is about relationships.

Let’s write about… war!

So back to war. How big is the narrative space we use to talk about it? Often it’s also very shallow. In this talk I’ll give you a few real-life examples of how to deepen it.

Narrative #1: Less killing, more war

One of the things I’ve found interesting from working on Virtual Battlespace over the years is the difference between what gamers think must be in a military FPS, vs what is actually there. In general video games are much more violent than actual military operations. Literally orders of magnitude more violent.

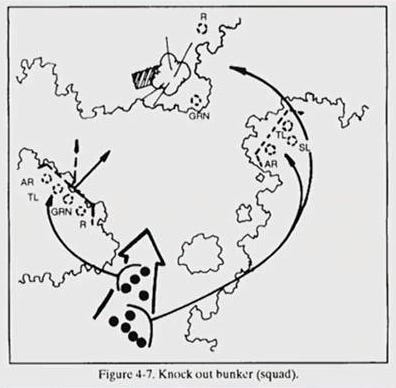

For example, the military generally want to attack with 3 times as many people as the defenders have. So if there are 30 defenders, you attack with 90 soldiers.

Imagine a level in a game where the player attacks an enemy base alone, and the level has 30 enemies. The player would single-handedly be doing the killing that 90 soldiers would do in real life. In effect that level would be 90 times more violent than a military simulator.

This makes sense if all your gameplay mechanics revolve around aiming and shooting. You really have no other design tool besides throwing bodies at the player to kill every few seconds.

Some games like Arma 3 are a bit more realistic. It uses simple tweaks to mechanics like “bullets can kill you easily” or “no healing, no respawn”, which force players to be more cautious about getting into fights. By letting you work with dozens of friendly troops–not just a few–its levels can look more like real life military operations. And by having massive terrain areas, part of combat becomes about positioning yourself long before you get into a fight. So the game gives you something to do in combat other than just shooting your gun.

But even in milsim games like Arma, there is still a focus on the most violent parts of war. You may be surprised to find the military often uses VBS to train less violent things, which you would never expect to find in an FPS.

For example, during the Iraq war, VBS was used for a lot of convoy training. In the picture below you can see a key feature, critical to this training. When we created VBS2 we actually forgot to port this feature from VBS1. The USMC refused to upgrade to the latest version until we added it back in, because they couldn’t do convoy training without it.

Turn signals: a key feature for military simulations

The feature: turn signals. Basically, the lead vehicle would use its turn signal to tell all the vehicles behind it that the convoy was supposed to make a turn ahead. They were training how to communicate and work together as a team. This is the kind of feature you normally find only in games like Eurotruck simulator. And it’s a critical feature a military simulator.

Below is another feature that prevented the New Zealand Army from upgrading until we patched it back in. They were training for peacekeeping operations in East Timor at the time, which was in the middle of a low-level civil war. What you see here is a checkpoint manned by Kiwi soldiers, a pretty common operation even in Iraq.

![]()

Weapons on the back: another key feature for military simulations

The feature: being able to put a weapon on your back. Why? Basically their rules of engagement at the time said: “if you see a guerrilla fighter with a rifle on their back, you leave them alone. If they have a rifle in their hand, you should shoot them.” This is basically an “emote” in an MMO, and it’s a critical feature in a military simulator.

We have literally thousands of features in VBS, to train for all kinds of things that happen in war. And many of them, like these examples, are not directly about killing people. There’s a lot more to war than just killing. It’s a really complex thing to win a war. Part of it’s because there’s just so many different things to do in a war.

Part of it’s also because it’s hard to even define what you’re trying to win. Which leads me to my next narrative.

Narrative #2: One war, many conflicts

One of the reasons I wanted to go to Afghanistan was to bring peace by helping to end the conflict there. As a Civil Affairs specialist, I had an interpreter and a bag of money for development projects. I would go talk to village elders, religious leaders, farmers, and try to win them over to support the Afghan. government. One thing I quickly discovered is that we weren’t in the middle of one simple conflict of “Taliban vs the Government”.

For example, the government troops were mostly ethnic Tajiks, Hazaras and Uzbeks from the north, but we were in the ethnic Pashtun region in the south of the country. There were centuries old rivalries between these groups. One time an Afghan army soldier told my interpreter–who was Tajik–that all Tajiks should be killed and then there would be peace. He was serious.

The Afghan army didn’t even speak the same language as the local civilians — they had to use our interpreters. The police in the other hand were all Pashtun, but were from different districts. They were fun guys to hang out with, but boy were they corrupt. They generally knew who and where the Taliban were… but instead of going after them, they preferred to arrest random locals and demand bribes from their families to release them.

Revenge is a very important concept in Pashtun culture. It’s one part of Pashtunwali, a deep cultural honor code. We always had to be careful not to get caught up in somebody’s feud.

Locally in Sangin district, there were two different tribes of Pashtuns, who also had been rivals with each other for centuries. Their members wanted to use the Taliban, NATO, and the Afghan government to extract revenge on the other tribe. For example, guy from tribe A might tell our intelligence that guy from tribe B is working for the Taliban, hoping we’ll go kick down his door and arrest him — or worse.

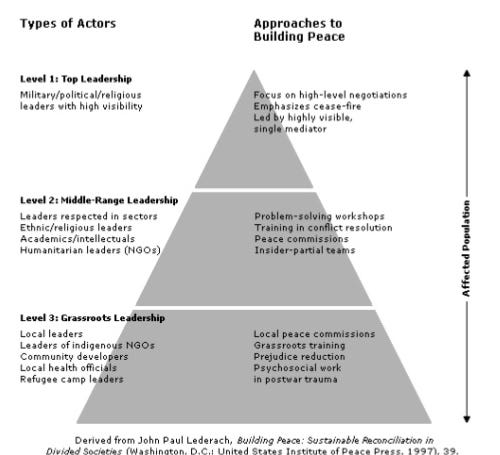

Eventually I came to realize there were many different conflicts, all mixed together inside this one war. You can imagine this as a pyramid. At the top there are just a few, high-level conflicts and actors. As you go down the layers, you get more conflicts between smaller groups. And because it is all happening in the same place and time, you end up with groups taking advantage of other conflicts, with shifting alliances, with backstabbing, and intrigue.

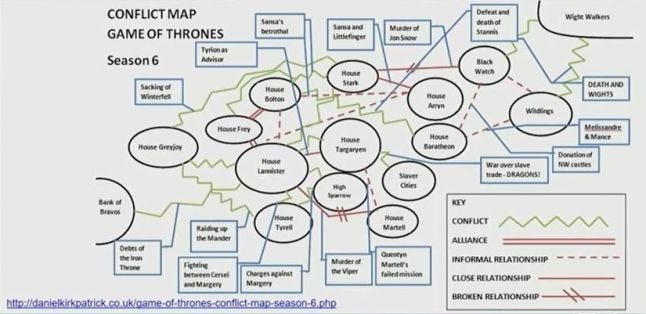

Game of Thrones is a perfect example of this in dramatic form. As you may know, the early books were inspired by a real war from English medieval history. There are so many conflicts, it’s hard to keep track of them all in the TV series, let alone in the books. Yet audiences love this stuff. Why?

I’d argue it makes for an engaging narrative loop. You start off with this sense of discovery as you first enter the world. You start naive, like Ned Stark: unable to see the game being played in the world around you. Once you finally start to understand the game, who’s playing it, and what their goals are, something changes everything. A new player enters the game, or someone switches sides, or some intrigue like the Red Wedding is revealed. And then you have to discover the game all over again. That’s an incredibly engaging core loop.

But is there enough room in video games for it?

Take