2019 was a groundbreaking year for accessibility awareness in the games industry.

We saw some of gaming’s biggest franchises leap to the front page of news publications (such as Forza, Gears of War, Spiderman & Tom Clancy) when their studios promised to take on improved accessibility. We saw platform owners get in on the action too, with Microsoft cementing it’s mantra of “When everybody plays, we all win” into it’s business strategy, as well as Nintendo thinking seriously about accessibility on the Switch with their magnification update.

This is seriously impressive because if you rewind further back to 2018 and asked us game developers about accessibility, we would probably say, “Don’t worry, we have subtitles”. It’s not that we didn’t care, but most of us didn’t understand the other issues or grasp the scale of the problem in modern games.

For me, the Game UX Summit Europe 2018 in April of that year was a turning point. One of my favorite experiences at the conference was understanding that UX designers have a solid role in helping our studios with accessible design, because nobody else had the time to think about it.

I had a bunch of discussions with people about this problem. One such discussion was with the amazing Ian Hamilton; a video game accessibility consultant and advocate. Ian gave a talk at the conference too, about the latest advances for accessibility in game releases of 2017 which included some interesting stats about how accessible game design benefits all players, not just those who need it. (If you would like to see this talk for yourself, I highly recommend you check out the YouTube video below)

<iframe title="Game UX Summit Europe 18 – Ian Hamilton" src="//www.youtube.com/embed/yGgCI0jhIQk?wmode=transparent&jqoemcache=6qXJF&enablejsapi=1&origin=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.gamedeveloper.com" height="482px" width="100%" data-testid="iframe" loading="lazy" scrolling="auto" class="optanon-category-C0004 ot-vscat-C0004 " data-gtm-yt-inspected-91172384_163="true" id="804166957" data-gtm-yt-inspected-91172384_165="true" data-gtm-yt-inspected-113="true"></iframe>In his talk, Ian also informed us about some impending legislation referred to as CVAA which was slated to take effect for all games featuring online communications in the USA at the beginning of 2019.

What is CVAA?

CVAA stands for 21st Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act, and was signed into Law in 2010 by President Obama. CVAA requires communication functionality (which it defines as text/voice/video chat) to be made as accessible as reasonably possible to people with disabilities, including the path to navigate to these features (regarded as “the ramp” to communication features).

Whilst the legislation was not specifically written for the gaming industry; when CVAA was proposed the FCC (Federal Communications Commission) did not anticipate the impact the law would have on games, and industry bodies fought for an extension to allow developers more time to create systems for accessibility in communications.

In our case at Splash Damage (making multiplayer shooters that utilize both text and voice chat), we need to be compliant, as almost all of our games encourage strategic team play and require good communication with teammates. This is a big deal for us to get right.

Because we need to make “the ramp” accessible, I want to discuss the high-level design for menu screens that are accessible by players without sight or with strong visual impairments. This then allows our engineers to create an interface that anybody can use to get to the features they wish. (For the purposes of this article, all example imagery will be game agnostic).

The Problem

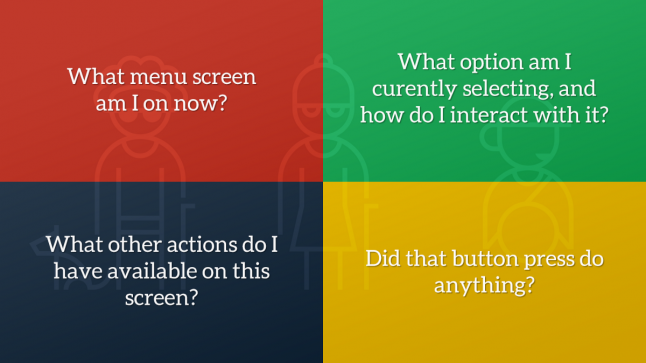

After conducting some initial research into gamers without sight, we learnt that when a visually impaired gamer interacts with menu screens, they are confronted with a number of challenges:

What menu screen am I on now?

What option am I currently selecting, and how do I interact with it?

What other actions do I have available on this screen?

Did that button press do anything?

Traditionally, users with visual impairments resort to relying on a sighted partner to help them through menus, utilize OCR (Optical Character Recognition) software to read text from screen captures, listen for audio cues to guide them or just brute force their way through the experience and use muscle memory to guide them in future sessions.

Whatever solution we designed had to remove this friction where possible, so they can comfortably navigate without the need for sighted assistance or guesswork.

The Solution

We chose to build a “narration system”, to read aloud menu text to the player as audio based on current screen information and the currently selected item. This concept is not new, as the web, desktop and mobile apps have championed this for some time, but doing it properly for games where not all needed information is available using focus is a challenge, and can often lead to overwhelming the player with all information at once.

In UX, Progressive Disclosure is a concept described when a feature that is used less frequently by users is pushed back in visual hierarchy, or to a secondary screen, to ensure that primary features are front and centre. We can take this concept and apply it to our narration system design; we plan to reveal all the simplest and most crucial information first, then layer on additional context if the player is still waiting for the right information. Let’s look at this in action…

Entering a New Screen

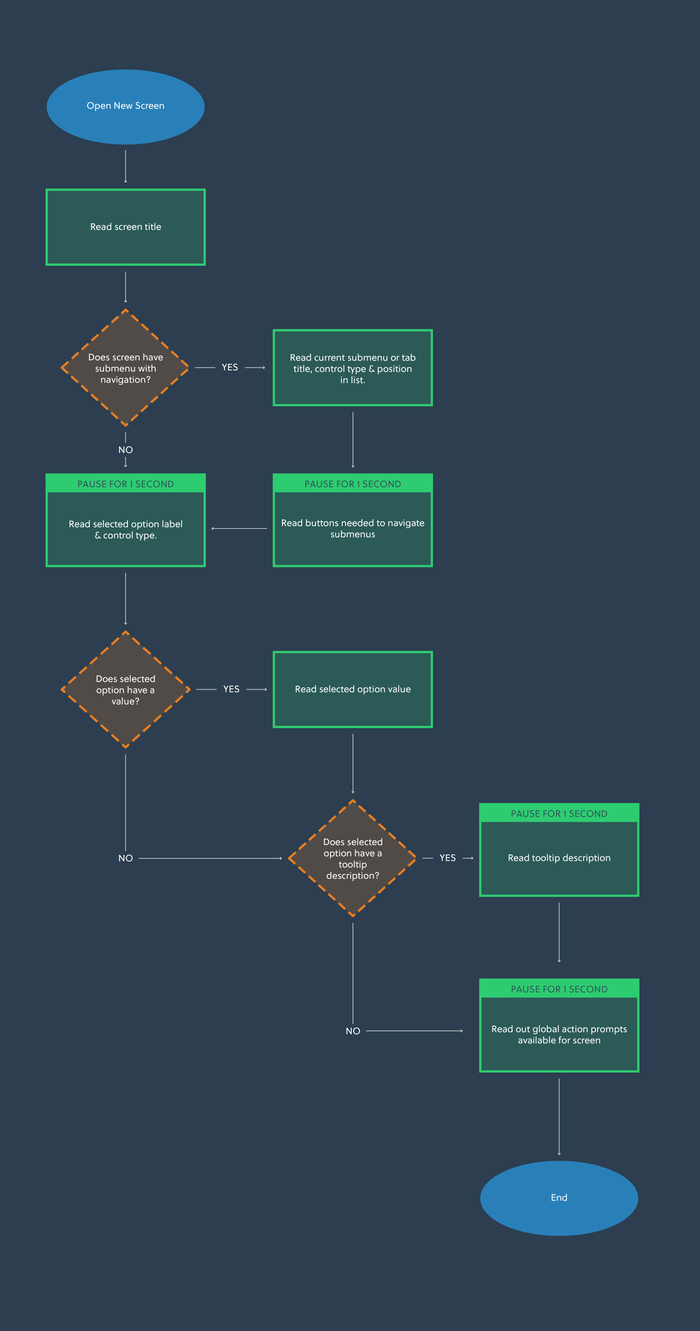

When a player enters a new screen, they need to know what screen they are on, what options they have to navigate or interact with and what buttons they need to press. They also need validation that their previous action got them to the right place.

With progressive disclosure in mind, a new player can take their time when they enter the screen as more contextual information is revealed to them, whereas an experienced one can quickly interrupt the narration and speed through the menus by taking an action early. So what does this mean for a menu screen?

Let’s take a look at an imaginary Settings screen:

<iframe title="Embedded content" src="https://giphy.com/embed/cMh8KEYztbHuJdWBII" height="360px" width="100%" data-testid="iframe" loading="lazy" scrolling="auto" data-gtm-yt-inspected-91172384_163="true" data-gtm-yt-inspected-91172384_165="true" data-gtm-yt-inspected-113="true"></iframe>If there is a submenu or tab system in place, it should read the selected tab category label and how to change it, so that the player knows there is more content on this screen than simple navigation will reveal.

In our UI, the first element in the list becomes focused by default. This means that default focused interactive element will narrate the text label, UI control type, value and tooltip description if available.

Once all focused narration is complete, we finish by appending narration for any global contextual actions available on this screen, so the player knows how to proceed when they have all the information at hand.

Global contextual actions are presented in a container of button prompts, often called an Action Bar, in the bottom of the screen. This tells the player which button to press to interact with the currently focused item, or how to access an entirely new submenu. For example, how to change the value of a selected setting, or how to open the global text chat overlay.

Here is a system diagram for how this might work:

For the example Settings screen we showed earlier, a new player may hear the following:

Settings Screen.

Controls - Tab - 1 of 5. Press Q or E to change tabs.

Controller Preset. Stepper - Standard.

Change the controller preset used in gameplay.