This article is only the first part of the study I have recently written about how Reed Hook developers used the player’s emotional engagement on Darkest Dungeon. If the subject seems to catch your eye, I encourage you to read the rest of the article.

This article is only the first part of the study I have recently written about how Reed Hook developers used the player’s emotional engagement on Darkest Dungeon. If the subject seems to catch your eye, I encourage you to read the rest of the article.

Disempowering fantasies in videogames

With the launch of the new console generation, Sony has decided to make Demon Souls (remake of an original title of the same name made in 2009 for the PS3) one of the most important releases for the PS5. For any veteran to the medium, the soulslike genre may not be the best decision in terms of accessibility for casual players.

Convoluted plot, rough gameplay demanding of reflexes and patience, and many deaths ensured to those who try to progress on enigmatic history are the main ingredients of Demon Souls, a game globally known for its difficulty. In which moment have the harshness and difficult comprehension of a game turn into unique selling points? What kind of player is attracted to titles with these characteristics?

The number of players has exponentially grown in recent times thanks to the uprising popularity of videogames, so developers have been preparing themselves to create a broad number of experiences enjoyable for the bast majority of players. This phenomenon known as casualization (Sarazin, 2011), has been enhanced due to the increasing division between players and how they choose the difficulty of their experiences. One clear example of this trend is the difficulty options Modern and Retro in the new Crash Bandicoot 4: It’s About Time (Toys for Bob, 2020) (Fig.1), that let the player choose between two gameplay configurations: Modern, a more casual approach to the game made for new and casual players; and Retro, which maintains the old life system reminiscent from the arcade era.

Fig 1. The different playstyles available to choose in the last entry of the Crash Bandicoot franchise are one of the latest examples of how games are adapted to different audiences.

When players perceived how the medium was changing towards the game experiences more accessible demanded by the masses, they began searching for different approaches to games. Indie games had just recently begun selling in the most important platforms, so the new potential buyers got there what they wanted, games not made for the typical player. Titles in which the metaphor or the mechanics are usually related to the phenomenon known as disempowerment.

Johan Huizinga, Dutch philosopher and historian, defines disempowering fantasies in his book Homo Ludens (1938) as game fantasies in which, voluntarily, the user has his power restricted in a safe and limited place with the objective of being entertained.

These restrictions are typical components found in a lot of indie and AAA titles. Disempowerment elements are usually seen in horror games, particularly in the Survival Horror genre, though it isn’t exclusive for them. Different videogames acclaimed for the critics such as Death Stranding (Kojima Productions, 2019), Alien Isolation (Sega, 2014) or Darkest Dungeon (Red Hook, 2015) have all in common their try to make the player feel vulnerable or weak against the game world that defies the user. These titles use various design tools in order to create the disempowerment, such as having limited survival resources for the player, making him or her see the power disbalance between their avatar and the enemies, or face harsh situations with bad outcomes.

Many times, game metaphors from this type of titles put the player under pressure in situations where our acts are morally grey, so the outcome of our own decisions falls under our own conscience. For example, Frostpunk (11 Bit Studios, 2018) (Fig.2) is a videogame where the player has to manage a small village in extreme winter conditions, having to choose many times about the disposal of villager’s corpses, child labor, food rationing, medicine and other resources.

Fig 2. Frostpunk faces the player with different extreme situations where the survival of the group is more important that the morality of our acts.

Fig 2. Frostpunk faces the player with different extreme situations where the survival of the group is more important that the morality of our acts.

Now that we understand how the market has adapted to offer this type of experiences, and that there is a audience large enough to maintain them we should ask, What is about these games that make them enjoyable for the player, even if they are defined by design to make us feel bad?

Defining the player: empathy and agency

When we talk about how games are an art form, we defend the interactivity and immersion of these experiences as the defining element that distinguish themselves from other cultural products. Nicole Lazzaro explains in her academic paper Why We Play Games: Four Keys to More Emotion Without Story that the immersion component seen in videogames is created by the moment-to-moment experiences inside them, only when the player comprehends the available actions (mechanics), objectives, capacities and limitations of the title.

It’s here where the role of the videogame designer comes in place, being his duty to search and create the phenomenon known as meaningful play. Defined by David Kirschner y J. Patrick Williams in Measuring Video Game Engagement Through Gameplay Reviews, the research explains how this technic helps the player incarnate their avatar with the most fidelity possible. To help create the desired experience, a game has to offer these 5 components:

- Challenge: knowledge and abilities necessary to accomplish our objectives.

- Control: different stages of decision making and impact over our surroundings

- Immersion: different grades in which the player is absorbed by the activity

- Interest: level of desire that the player has in order to do something

- Motive: perceived value of the activity, which requires effort.

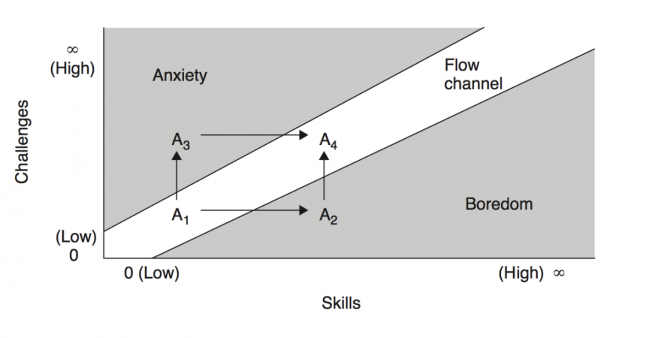

Among these 5 elements, challenge and control are the most important of the list, because those two generate the immersion, interest, and motive in the player. About how challenge works, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi writes his famous flow theory, which not only applies to videogames. Flow is defined as a state of concentration or complete abstraction produced by the activity that is taking place. The most efficient way of creating this effect on the player is introducing a challenge that grows in difficulty at the same time as the player skills do.

Fig 3. This chart from “Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience” shows how the Flow channel works. If the challenge is much bigger for the player, we will generate anxiety on him/her. But if it is perceived as simple for the user skills, he/her will get bored.

Fig 3. This chart from “Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience” shows how the Flow channel works. If the challenge is much bigger for the player, we will generate anxiety on him/her. But if it is perceived as simple for the user skills, he/her will get bored.

Then, when the connection between player and game is positive, the subject will have the time and motivation needed to understand the remaining game elements, thanks to him/her being fully immersed in the gameplay. When we are in the flow channel, the actions and relations of our avatars feel like if they were real to us. As Harrison Pink says in his GDC 2017 talk called Snap to Character: Building Strong Player Attachment Through Narrative: as the player and his/her avatar progress together and spend time with other characters of the same game world, the user will start to create emotional bonds with them.

Those emotional bonds can’t be imposed to the player, because they require time and adaptation to the game universe, including all the presented characters. Empathy and other emotions that the user may feel can affect how him/her faces different game situations, because the human factor can make us act different towards situations where our friends/foes are involved. This phenomenon is called Emotional Inertia and it is one of the most valuable signs that show a high level of immersion.

At the same time, a player that feels empathy for the other characters trigger’s that all our actions regarding their future or wellness are transformed into moral decisions, due to the moral implications that they have on the user. We feel then that our actions and abilities have consequences that can influence the game world and plot, creating the sense of agency.

Making an impact in a fictitious world

The Player Agency, defined by Karen and Simon Tanenbaum in their paper Commitment to Meaning: A Reframing of Agency in Games as the satisfactory sensation of being able to take important decisions and see the results of their actions.

As we commented before, immersion through the use of player emotions is a clear example of how significative this experience is for him/her, so emotional inertia is a phenomenon that designers look forward to. In order to improve those emotional bindings we know that the player needs an adaption time, but as Meg Jayanath explains in her GDC 2016 talk Forget Protagonists: Writing NPCs with Agency for 80 Days and Beyond, that empathy flourishes in the player not only when the characters have the same objectives as we do, but when they show human traits that makes them feel real. It is accomplished by letting us share moments with them where we see how these characters are affected by the positive and negative parts of the adventure, remarking the bad side of it. That’s because the effort and loss suffered from those characters makes us see them as our true companions.

Immersion, agency and empathy are fundamental components for the design tool responsible for this behaviour, known as emotional engagement, defined by Kiel Mark Gilleade and Jen Allanson in their academic paper Affective Videogames and Modes of Affective Gaming: Assist Me, Challenge Me, Emote Me (2005) as using player emotions as an element that is going to influence his/her actions.

A clear example of the use of this design tool can be seen in titles that build their gameplay and progress around how the player connects with characters from the game world, who will help us progress and upgrade our town. Those kinds of games offer almost complete freedom to the player. Animal crossing: New horizons (Nintendo, 2020), The Sims (Maxis, 2000) or Stardew Valley (Eric Barone, 2016) are examples that have the mentioned characteristics in which the objectives in our gameplay are influenced by the relations with other characters (Fig.4).

Fig 4. In Animal crossing: New Horizons, our relations with our neighbors will be upgraded if we accomplish some missions or tasks for them, such as bringing them gifts based on their likes, asking them about their day, or bringing them their lost objects.

Fig 4. In Animal crossing: New Horizons, our relations with our neighbors will be upgraded if we accomplish some missions or tasks for them, such as bringing them gifts based on their likes, asking them about their day, or bringing them their lost objects.

So, when a videogame fulfills all the basic requisites (challenge, control, immersion, interest, and motive) needed for it to create a significant experience in the player, he/her will be more inclined to generate emotional bonds with the game world and their characters. Then, designers use the emotional engagement created in the users to create significative experiences that resonates with them.