Deep Dive is an ongoing Gamasutra series with the goal of shedding light on specific design, art, or technical features within a video game, in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren't really that simple at all.

Check out earlier installments, including using a real human skull for the audio of Inside, and the challenge of creating a VR FPS in Space Pirate Trainer.

Who: Owen McCarthy, Principal Programmer at Frontier

My name is Owen Mc Carthy. I am a principal programmer for Frontier. I studied Computer Science and Theoretical Physics at University and did an MSc in Game Development at the University of Hull before joining Frontier nine years ago. I usually end up working on something physics or simulation related.

I worked on reactive water simulation and the physics in Kinectimals. I’ve worked with some really fun signal processing on Kinect Disneyland Adventures so we could map the player’s movements to their in-game avatar with as little jitter and lag as possible. I then worked on building destruction and ragdolls for Screamride.

Most recently I worked on the crowd simulation in Planet Coaster. I really love building believable worlds, and game development is definitely the place to be to make that happen.

What: Building Believable Crowds in Planet Coaster

For Planet Coaster, we wanted to make the best-ever crowds in the SIM genre. That meant huge numbers, few intersections, and novel approaches to sound, art and animation.

In Planet Coaster’s voxel-based sandbox we wanted to simulate 10,000 park guests at once and we wanted them to look like a real crowd. We also wanted them to be able to handle curved paths, which had proven a challenging task in crowd simulations from our previous games but something we considered essential to Planet Coaster.

Traditional pathfinding methods aren’t suitable for simulating huge numbers of characters in real time. Usually each agent would compute a path separately and then move along it, but this tends to be very expensive and doesn’t scale well. Trying to add collision avoidance afterward becomes a mess of edge case handling.

We use potential/flow fields to simulate the crowd in Planet Coaster. We have parallelized the computation across CPU cores and frame boundaries to minimize impact on the frame rate. We also had to implement non-standard approaches for sound, art and animation systems.

Why?

At the beginning of Planet Coaster’s development we knew we wanted to move the genre forward. One thing I was particularly invested in was bringing the atmosphere of a real crowd into our virtual world, and in making each park guest aware of their surroundings. I wanted to capture little moments like walking by an entertainer doing silly things and seeing other guests watching and reacting.

We reviewed the state of the art in relation to crowd simulation and navigation. That involved reading lots of research papers, studying techniques and analyzing the feasibility of each one, taking into account scalability, memory usage and CPU performance. We watched hours of footage of crowds moving around theme parks, and we captured footage of our own.

10,000 guests was the number that we targeted right from the beginning, and simulating each one individually seemed like a real challenge, so we focused on a smaller number. There are fewer goals in a theme park than guests; rides, coasters, shops and facilities are all goals. This was where the technique of using flow/potential fields became very appealing.

Instead of computing a path from A to B for each person, a path from each goal to all possible positions is computed. The question was, ‘can we simulate a few hundred goals in a flow simulation more cheaply than we could simulate 10,000 individual paths with something like the A* algorithm?’

Crowd flow

We had prototypes of several different Planet Coaster technologies in development in parallel. We started development on a voxel based landscape system, and we really wanted to break out of the traditional grid-based path system. Ultimately the crowd system would need to be integrated with the voxel terrain and path systems, but early in development they were still unknowns so the crowd system had to be robust enough to fit whatever these systems became. It was easier to develop this crowd prototype in isolation, but to be constantly aware of making it amenable to changes elsewhere.

The crowd system was much more robust as a result of this separation. Requests for changes to the path system throughout development were little to no work to integrate with the crowd system. The crowd system just deals with shapes to add to its flow simulation and it doesn't really can about the source of them. For example: During the first alpha we could only have straight elevating paths. It would have been possible to exploit this fact for ease of implementation of overlapping paths, but later on the designers wanted to have curving elevating paths and they implemented them they just worked fine with the crowd system and became a feature for the second alpha release!

I started creating a flow simulation on a flat grid-based system to begin with, but flow fields for each goal don’t interact with each other directly. The interaction happens indirectly by resolving around a density and velocity field generated from all of the guests in the simulation. These flow fields exhibit many of the properties found in high density real crowds. They interact with each other and flow around each other and form emergent structures like lanes and congestion, and they allow agents to flow around congestion.

I think the best way to imagine how a flow simulation works is to picture a table with raised edges. Inside this table is your park and its network of paths, and each goal point has a different water tap connected to it. Scattered across the table are marbles which will flow with the water. When you want to solve a particular goal, you turn on that tap and watch the water flow through the path network and push the marbles around. Each tap can only move its set of marbles and other taps’ marbles are frozen in place as obstacles.

We record the velocity of the ‘water’ every time it flows into a new cell on the table. Once the entire table is filled with water, you’ve effectively ‘solved’ the flow field away from that goal. Now you can reverse the direction of the flow, pick any point on that table and inspect the velocity of it, and it is now directing the particle to the goal!

You can now put as many agents as you like anywhere on that grid and you instantly know which way they need to move to get to that goal. You can keep this velocity field in memory until a new one is computed and continue to flow agents on the existing data.

Figure 1: In essence, you’re propagating a wave through a grid and recording the velocity of a wave the first time it enters every cell.

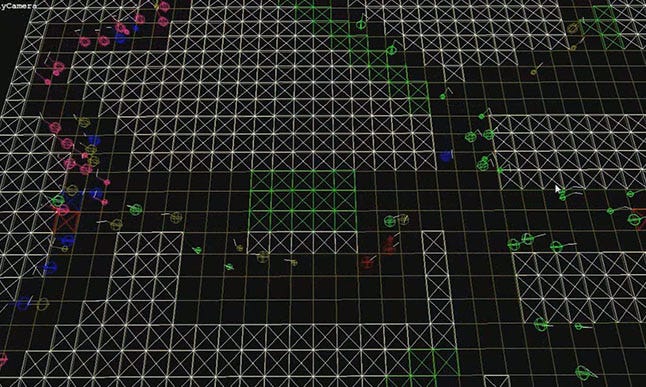

When this prototype was up and running with really simple debug rendering and spheres for each guest, we needed to test the CPU and memory performance to see if this technique was viable at the scale we were aiming for. We built a stress test map with the same dimensions as the target map size. This map had a few hundred goals and about 10,000 agents on it. While memory usage was a little bit over budget, we were confident that eventually we could drastically reduce it. The CPU usage was heavy but the system was single-threaded at this point. We already had a vision to parallelize the simulation so that it wouldn’t be a limiting factor.

Figure 2

Animation

It was now time to get rid of the debug rendering. The art team had already started taking the concept art and turning it into models we could use. Each guest was planned to have interchangeable body parts with lots of texture and skintone variation. We have a great animation team at Frontier, with lots of experience making quality animations, but due to the number of guests we needed to limit the animation blending that could take place.

Front-facing characters in game animations typically use bone space blending with many layered animations, which makes it expensive to compute the non linear final bone transformation. Instead of this we store the bone transformations from every frame (not keyframe) of the animation in memory and use a simple linear interpolation of the nearest two frames. This leads to simpler-looking animations, but we felt we could do better and still be efficient with clever authoring and cross-fading.

Crossfading is a much cheaper model-space linear blend between two different transforms, but can cause skeleton constraints to be broken, so we have to be very careful when we cross fade. We authored a lot of the animations with the legs in lockstep with each other so the upper body was free to do other things, and we could crossfade at any point in the walk cycle animation to another reaction animation without the legs crossing, losing momentum or sliding. This allowed us to benefit from bone-space blending quality transitions, without all the computation expense that goes with it.

We also wanted to have lots of variation in the animations and didn’t want the guests to look repetitive, which is harder to do when blending is limited. The animators were already busy recording footage of how people move as individuals and in groups, so we analyzed this footage and were able to break down the animation cycle into a very modular system. We settled for four or five variants of the base walk cycle, each under two seconds long. Every time one of these animations was finished, we were able to transition to another without blending, and build up a very dynamic and long walk cycle.

We also had a suite of animations for awareness, needs and feelings – tired, fed up, pointing, laughing, needing the toilet etcetera – that we could plug into the animation timeline when the guests are reacting to things in the park. By the time Planet Coaster shipped I think we had upwards of eight minutes of animations per skeleton type we could plug into this system.

Figure 3:

We also spent some time looking at how the guests would behave in a group or family. Due to the nature of flow fields, you can’t easily ensure different particles will stay together even if they are going to the same goal, as the flow dictates where each individual particle moves. The solution was to put groups into a single particle in the simulation and move them as one unit. Each group has a radius within which members can move without affecting the flow simulation. Originally the family members were locked in formation but this looked very odd, especially when they turned corners, so we programmed in more freedom so they could rotate individually inside the particle so the relative positions of family members would move and shift over time for a more convincing look.

For more details on animation, take a look at https://www.google.com/url?q=https://medium.com/@nicholasRodgers/applied-matrix-maths-for-complex-locomotion-scenarios-in-planet-coaster-9b5743bd805c%23.b7oebz2ju&source=gmail&ust=1483618494398000&usg=AFQjCNEVPEOn_0XnJN7B11uU-BhHqNowHw" href="https://medium.com/@nicholasRodgers/applied-matrix-maths-for-complex-locomotion-scenarios-in-planet-coaster-9b5743bd805c#.b7oebz2ju"; target="_blank">this blog post by Frontier’s Head of Animation, Nick Rodgers.

Audio

At this point we could see our prototype was going to be the way forward. The large number of guests was becoming a reality so we had to think about how things were going to sound. Traditionally with video game sounds, you usually put a sound emitter on each object/guest that would make a sound, but with 10,000 guests it would sound chaotic and would be prohibitively expensive.

We wanted to get a very accurate representation of the crowd ambience, and Frontier’s sound designers were already thinking of building a coarse representation of the density of a crowd and their emotions for this purpose. With the flow simulation we already had crowd density data available for the general crowd ambiance. We could then layer ‘fine detail’ audio on top of the crowd ambience so the members of the crowd nearest to the camera would have distinct sounds and conversations, which really brought the guests to life.

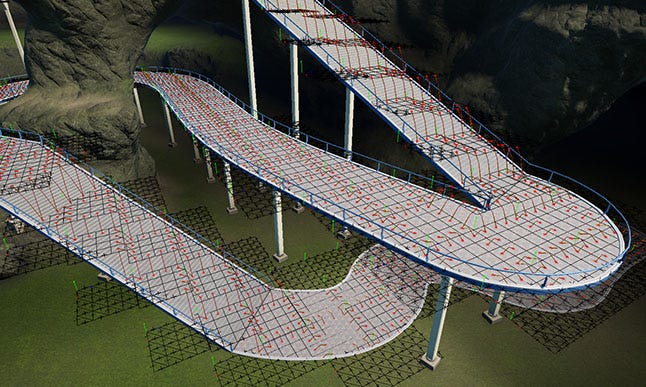

Further challenges

By this time the path system prototype’s development had finished and we had chosen a crowd system to go with. The next big challenge was how this crowd prototype would work with the voxel-based terrain and the curved/elevated paths instead of a traditional heightmap. With Planet Coaster’s voxel terrain and free path system, you can overlap paths and terrain on top of one another, making it more complicated than the simple ‘table’ prototype.

To combat this we decided to break up the grids into much smaller chunks and connect them with virtual connections. The large grid in the prototype image in Figure 2 would be broken up into smaller 4m x 4m grids. To make the entire terrain traversable would require enormous amounts of memory as each distinct goal needs a persistent record of the velocities of each cell, but by only allowing guests to navigate paths we only need smaller grid segments to exist when there is a path in that area, keeping memory usage down.

Each path section would be rasterized to these smaller grid segments, activating cells in them and creating new segments when necessary. When a cell is activated the height of the path is also computed at that point, so each grid also has a heightmap. This meant that when we needed to set the height of the particles it was a quick lookup into the heightmap, instead of raycasting into the voxel terrain. Doing 10,000 raycasts every frame into the voxel terrain to determine the height of each guest was something we wanted to avoid!

The connections between grid segments were very hard to visualize when dealing with overlapping paths, but hopefully you can understand it after looking at the picture below which shows the debug rendering of the grid segments and virtual connections.

The connections between grid segments were very hard to visualize when dealing with overlapping paths, but hopefully you can understand it after looking at the picture below which shows the debug rendering of the grid segments and virtual connections.

Figure 4: The red lines are connections between cells, and the inactive cells in the grid segments have slashes through them. Each grid segment is a 4x4 block of cells

Figure 4: The red lines are connections between cells, and the inactive cells in the grid segments have slashes through them. Each grid segment is a 4x4 block of cells

The connections were probably the most difficult part of the simulation to get right as it adds a lot of overhead to the data structures that has to be precisely maintained when paths are added and removed. The ‘Undo’ and ‘Redo’ feature of

No tags.