In November of 2016, a small group of veteran game designers got together in a remote portion of Texas for a think tank called Project Horseshoe. Our workgroup dug deep into how design can help build meaningful relationships within games. You can read the other reports here: http://www.projecthorseshoe.com/reports/

Our group consisted of:

Daniel Cook, Spry Fox

Yuri Bialoskursky, Electronic Arts

Bill Fulton, Microsoft

Michael Fitch, Betterrealities.com

Joel Gonzales, Wargaming.net

Introduction

The issue

In many online multiplayer games, players enter as strangers and remain strangers. Due to a variety of unquestioned logistics, economic and social signalling choices, other human beings end up being treated as interchangeable, disposable or abusable. We can do better.

When we throw players into a virtual world without understanding the cascading outcomes of default human psychology, we are little better than an unethical mad scientist replicating Lord of the Flies. As game designers, we’ve been building destructive dehumanizing systems. We should take responsibility for the bullying, harassment and wasted human interactions that inevitably results.

Let’s instead design games that help strangers form positive pro-social relationships.

New tools

There’s a mature body of research going back to the 1950s concerning how to create systems and situations that facilitate positive relationship building between strangers. Given the right context, people will naturally will become acquaintances. And a smaller number will become friends.

Much of this research focuses on describing how friendship forms in observed communities. Or how an individual might go about developing friendships. We propose intentionally using these psychological insights in a highly scalable online game designs to engineer potentially millions of healthy player relationships. Many games accidentally separate players and decrease the chance of meaningful human contact. What if we design our games to be more socially meaningful?

We can’t force two people to become friends, nor should we want to. But we are in a unique position to build systems that create fertile ground for friendships to blossom. And by carefully nurturing positive relationships, we can simultaneously avoid naively birthing poisonous cesspools that actively fosters hate.

This paper cover a simple design checklist based off well supported models of friendship formation. Put it into practice and you will create games that build stronger player relationships and stronger communities. In addition to making the world a better place, your games will likely have better retention and improved monetization because you are creating value for your players that speaks to their deeply human psychological needs.

General Model

To build friendships, your game should facilitate four key factors. When these are present, friendships tend to form.

Proximity: Put players in serendipitous situations where they regularly encounter other players. Allow them to recognize one another across multiple play sessions.

Similarity: Create shared identities, values, contexts, and goals that ease alignment and connection.

Reciprocity: Enable exchanges (not necessarily material) that are bi-directional with benefits to both parties. With repetition, this builds relationships.

Disclosure: Further grow trust in the relationship through disclosing vulnerability, testing boundaries, etc.

What sort of friendships does this model cover?

We define a friend as another person with whom you have a mutually beneficial long term relationship based off trust and shared values.

There’s a spectrum of friendship ranging from acquaintance to best friend. Different cultures have very different definition for what it means to be a ‘friend’. Americans for example, tend to call relatively distant acquaintances ‘friends’ while a country like Germany may reserve the term for two of three closest relationship. In this paper, we treat friendship as a spectrum that ranges from stranger all the way up to deep intimate friendship.

In particular, we focus on the transition from stranger to acquaintance. This is the step that most often falters in modern game designs.

What types of games can use this friendship model?

For the purposes of this paper, we are interested in a specific domain:

Online: Players are not in the same physical space.

Mediated: A computer mediates all interactions between the players. Rich in person channel of communication like one might find in a board game or sport are not available.

Synchronous: Players are interacting in real time via keyboard, mouse, mic, controller, voice, emote, etc.

Other types of games benefit as well, but they have their own complexities that are outside the scope of this essay. Local multiplayer taps into high bandwidth interpersonal communication and often occurs between existing acquaintances. Asynchronous multiplayer relies heavily on a strong reciprocation loop to compensate for a weak sense of proximity.

1. Proximity

What is Proximity

The first factor to consider is Proximity. Social proximity is the likelihood of players seeing and having the opportunity to interact with one another in a game space. This space can be virtual like a chat room. Or it can be spatial like a room in a game match.

Think of proximity in terms of simple logistics. If players can’t see one another they can’t initiate the reciprocation loops and any friendship is impossible. Without proximity, friendship is impossible. In some sense this is an obvious requirement, yet in many games we create strong barriers to simply being together.

Concepts for Proximity

Density

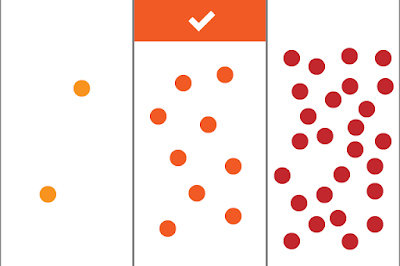

A high density game is one with a low amount of distance between players so they are likely to bump into one another. A low density game is one with a large amount of distance between players. Often we design in terms of ‘number of players’ and independently think about ‘size of map’. However, density, the ratio of these two factors, is often the key attribute to balance.

Frequent serendipitous meetings

Due to high density, people are likely to ‘randomly’ bump into one another repeatedly. This creates exposure and familiarity between strangers. Meeting the same person again and again feels like magical fate, but it is primarily the outcome of well designed statistics and logistics.

Crossing class, race and age boundaries

The single most effective method of creating friends that cross traditional social boundaries is to put two people together in close proximity. People form friendships with those that are nearby and if their choices are limited, they’ll form choices with those that would not be their instinctive (often biased) choice.

Connection to other requirements

Reciprocation: Being the in same space yields parallel play. This eventually leads to low cost reciprocation loops between players

Similarity: Being in the same place lets players observe similarity. Note that in studies of friendship formation, being in close proximity is a stronger predictor of friendship formation than being alike. However, the impact of distance falls off quickly and once players start rarely being close together, they will start forming friendships predominantly based off similarity.

Proximity Patterns

Player Identification

Other players need to be identifiable. If you see someone a second time, would you know it? Names, unique clothing, identifying animation or abilities all help players understand that they are seeing the game person again and again.

Persistent spaces