This post originates from the site Narrative Construction, whose goal is to offer a hands-on approach to designing an engaging and dynamic game system from a narrative and cognitive perspective.

In response to the comments I received on the series Putting into play I have produced a set of patterns showing the hands-on structuring of narrative and cognitive elements. Additionally, it keeps my time restraints from holding back curiosity.

At the end of the last chapter on pacing, I linked a talk with the Witcher 3: Wild Hunt lead quest designer Pawel Sasko explaining an "interpretation-hypothesizing" model helping the team set the gameplay's core based on how the player thinks, learns, and creates meaning.

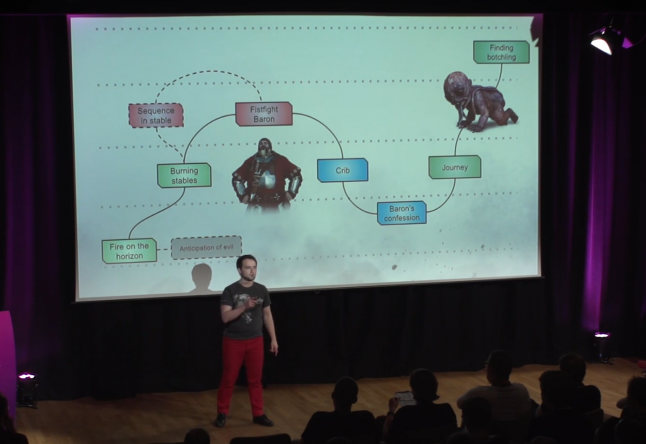

Below you can see Sasko illustrating how the team predicted and controlled the player's thinking by making the player anticipate evil (see the gray-colored box) and where the desired outcome was to make the player feel guilt at the end of the quest sequence.

Pawel Sasko explaining an "interpretation-hypothesizing" model

Pawel Sasko explaining an "interpretation-hypothesizing" model

It is unique to find examples where a team so outspokenly proceeds from a cognitive model. Mostly, the predictions (mind-reading) of the players' cognitive activities are handled on an intuitive level, making the overview of the player's process of causal, spatial, and temporal links tricky to discern.

To visualize how to predict a player's thinking, I will use the narrative and cognitive elements below and highlight the goal to show how the differentiation of cognitive and behavioral goals helps you control the player's meaning-making in sequencing a motivating space.

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale) Narrative and cognitive elements

Narrative and cognitive elements

The elements are a part of the cognitive modeling method, Narrative bridging, which I use in various forms to depict how you create meanings that engage and motivate the player.

I will proceed from Sasko's quest example in the Witcher 3: Wild Hunt where the player plays a monster slayer looking for his missing adopted daughter. In addition to Sasko's example, I will show Lucas Pope's game Papers, Please, where the player works as an immigration inspector at a border control station, controlling travelers' documents and permitting those whose documents are in order to enter the country of Arstotzka.

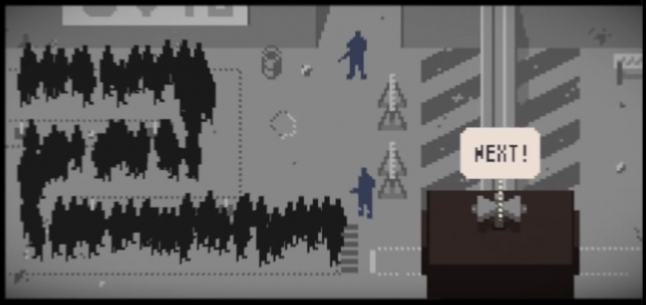

Lucas Pope's game Papers, Please

Lucas Pope's game Papers, Please

To follow the designer's predictions, I will use green color, and to depict the player's thinking, I will use the purple color.

I recommend reading the series Putting into play to learn more about the theories and principles behind the narrative and cognitive elements. You can find the links at the end.

Cognitive - and behavioral goals

The key to predicting and controlling the player's meaning-making is differentiating between cognitive- and behavioral goals when sequencing time and space.

Cognitive goals concern our understanding, learning, and meaning-making. What is important to consider from a designer's perspective is that we are goal-oriented and can keep numerous goals in mind, which we organize by ranking and categorizing them. So when the player is processing information and comes to a conclusion, assumption, inference, hypothesis, or decision, the player isolates a goal to achieve an objective.

From a designer's perspective, the player's isolation of a goal is always considered to affect the player's behavior. The control of the player's isolation of a goal can either be strictly held by the designer or the player. By thinking in terms of goals to be controlled (isolated) by the designer or the player, broadens the understanding of the concepts of emergent (open) and embedded (closed) game spaces. The latter commonly refers to the canonical story structure's impact on the player's freedom to make choices and where the open space is considered to provide more freedom. But as we go, you will see more factors driving the experience that makes the space feel restricted or open.

From a cognitive perspective on the design of engaging and motivating experiences, a choice can be an internal or external activity. Meaning, the choice doesn't have to lead to a physical output and could stay in the player's mind (memory). So when you structure a game space, you consider the behavioral goal to be an internal or external activity.

Internal activities

expecting, anticipating, hypothesizing, interpreting, imagining, predicting, forecasting, estimating, planning, comparing, distinguishing, etc.

External activities

gathering, collecting, collaborating, finding, searching, surviving, harvesting, crafting, building, etc.

The control (isolation) of the player's internal and external activities is made by sequencing space and time to create dynamic gameplay. The control you gain from sequencing the space also explains why I removed the acts, turning points, etc., in Putting into play. The removal of the familiar elements of the canonical story structure helps you sequence directly for the game's media-specific elements and systems the player's internal and external activities in creating a motivating core loop.

Sequencing external and internal activities

To show how you organize the cognitive and behavioral goals, I will create a graph showing a learning-curve (1) and a timeline (2).

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale) Figure 1 Showing a timeline and a learning-curve

Figure 1 Showing a timeline and a learning-curve

The learning curve (1) visualizes the space by how the player's understanding, learning, and meaning-making arrives at states of cognitive goals that affect actions and behavior.

The timeline (2) assists in overviewing behavioral goals' sequencing to be internal or external activities.

Sequencing external activities

Starting with Sasko's quest sequence, let's look at the timeline (2) and the sequencing of external activities as they are the easiest to discern.

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale) Figure 2 Sequencing external activities by breaking up the timeline

Figure 2 Sequencing external activities by breaking up the timeline

The sequencing of the timeline (2) is broken up into quests based on a canonical story structure. Each quest encompasses the external activity of finding (5), meaning the sequence isolates the behavioral goal of achieving an objective.

The start (3) and end (4) of the quest to find (5) the Baron is a part of a causal network of quests, whose overall goal is on finding (5) the adopted daughter at the end of the timeline.

In Papers, Please, Lucas Pope has broken up the timeline (2) into days and where the start (3) and end (4) of each day encompasses the external activity of permitting or denying (5) travelers entry.

But before we take a closer look at the cognitive goal of choice by how each sequence captures the dynamic interplay between permitting or denying (5), let's return to Sasko's quest sequence to see how the external activity of finding (5) merge with the player's internal activities.

Sequencing internal activities - Sasko example

To understand how you make the player anticipate evil at the start of the quest (3) and feel guilt at the end (4), I will illustrate how the player's thinking works from the position of a present when entering the quest sequence (3).

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale) Figure 3 Player’s thinking from a present position

Figure 3 Player’s thinking from a present position

By setting the position of the player at the start of the quest sequence (3), you can survey how the player is processing objectives from the past (6) to understand the future (7) from its present position (3).

The drive-state of anticipating evil from the player’s position (3) is a processing of the experiences learned in the past (6), which influence the internal activities of the player’s expectations on the future (7). Making the player feel guilt at the end of the sequence (4) concerns altering the experiences the player has learned in the past (6) that will change the expectations when the player arrives at the end state of the sequence. Meaning, the expectations of evil will change.

To make the player expect evil, it means there must be good, or at least some lesser evil, so you can alter the experiences and expectations. In the chapters on pacing in Putting into play, I explained how you engage the player’s meaning-making by employing causal contrasts. Creating a motivating core that engages the player’s meaning-making (learning) contrasts work as triggers. Applied to the timeline (2), contrasts turn cause (past, 6) and effect (future, 7) into a motivating propeller forming a dynamic core loop.

Through the causal contrasts, you control the player’s behavior by switching between the cognitive and behavioral goals over time.

When defining the premise of what you want the player to experience or feel, the causal contrasts capture the core of the overall goal of the learning curve (1).

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale) Figure 4 Transforming experiences into expectations

Figure 4 Transforming experiences into expectations

The experiences and expectations (meanings) you want the player to learn (build) along the timeline (2) comprises the internal and external activities to form the dynamics of the overall experience (1).

When the player is undertaking the external activity of finding (5) the Baron, the internal activity of