The following is an excerpt from a near-complete edition of Stay Awhile and Listen: Book II – Heaven, Hell, and Secret Cow Levels, now funding in ebook and paperback formats on Kickstarter, and is subject to change. Stay Awhile and Listen: Book II chronicles the making of StarCraft and Diablo II, and reveals never-before-known details about cancelled projects and the history of Blizzard Entertainment and Blizzard North.

DAVE BREVIK'S MORNING routine was a critical component of Blizzard North's success, though it was only nominally a "morning" process. He worked late, slept in, and after rolling out of bed, dragged himself into the shower and cranked the hot water to full blast. Closing his eyes as steam curled up around him, he rested his head against the tiled wall and let his mind wander. After a few minutes, his eyes popped open. He scrubbed and dressed quickly, hopped into his sports car of choice, and screamed down the highway to Blizzard North, where his employees watched him stride through the front doors and into the bullpen, face aglow. His arrival was met with a mixture of excitement and trepidation.

"Even though he was a programmer and I was an artist, Dave Brevik is someone I view as a real talent in the industry," Eric Sexton said. "His unique vision really inspired me. At least two or three times a week, he'd come in, like, 'I was taking a shower, and I had this idea.' And he'd tell you the idea, and you were like, 'That's amazing!' Then he'd sit down and do it, and within a day he'd have this amazing idea up and running."

"It wouldn't always be major," Dave Brevik chimed in. "Sometimes there were things like, we really need some extra tests. I'd stand next to somebody's desk and talk to them about this idea I had in the shower."

The biggest of Dave's ideas tended to be double-edged swords. Weeks or months of work could be tossed out in favor of what he preferred to do instead. "Every morning we'd talk about what we were doing, how the bugs are, what we need to do for that day," Jon Morin remembered. "Then Dave would come in and go, 'I was in the shower this morning and I had this idea.' Whenever we heard that, we'd go, 'Aww...'"

Left to right: David Brevik, David L. Craddock, Erich Schaefer, Max Schaefer

Left to right: David Brevik, David L. Craddock, Erich Schaefer, Max Schaefer

Even programmers cut deepest by that sword acknowledged that its other side was just as sharp, albeit sometimes in hindsight: Many of his design elements went on to position Diablo II as the definitive action-RPG. On one late morning, Tyler found himself in Dave's crosshairs. "He said, 'We're not going to load in between levels anymore. Tyler, you can make that happen.' I said, 'Uh... okay.'"

"It was very collaborative. So collaborative that I can't even remember where certain things came from."

Dave's latest proclamation derived from Ultima Online. As much as he liked the game, Dave never shied away from ranting about its flaws. Excessive load times was one of his more frequent complaints. Staggering in its scope, Ultima Online's world was cordoned off into zones out of necessity. Most players still had dial-up modem connections in 1997, and the game's servers could only send and receive data from each player so quickly. When players left a major area, the game briefly paused the action to load in the next zone.

Zoning was slow and cumbersome, Dave Brevik declared, and had no place in the fast-paced world of Diablo. Tyler agreed and got to work on a solution. His approach was to only simulate what players could see on the screen. Terrain beyond the borders of the player's monitor waits to come to life until players come within a certain range. Monsters and items, however, are exceptions. Players can leave fallen trinkets and piles of the gold on the ground, explore and fight elsewhere, and then return to pick up dropped goods. Certain monsters, such as those with ranged attacks, become aware of players before players see them, enabling monsters to lob arrows, spells, or other attacks ahead of time while simultaneously cluing players in to their presence by means of filling the screen with projectiles.

As players move, the game's algorithms sew tiles together faster than players can see it happen so as not to dispel their immersion in the game world. "You can outrun a monster and it would just stop, because we didn't care about it anymore," Tyler explained. "Then what's left behind is cached and made rather small, so we don't have to worry about it. So, levels would be made as you go, and it'd become more and more detailed."

Algorithms weave Ben Boos' tiles into quilts of fields and pastures, caves and temples. Dirt trails connect regions like beads on a necklace, so players can find the way forward once they tire of exploring by venturing back onto the beaten path. Areas are divided by barriers that fit the environment, such as low stone walls in meadows. An area's barriers lead to narrow land bridges that in turn leads to the next zone. The name of the new area pops up on the screen, feeding players' sense of discovery and progress.

Although the team had settled on building Diablo II as a 2D, pixel-art game in the vein of the original, Dave Brevik was determined to tap into the burgeoning graphics card market. Perspective Mode, a pseudo-3D display mode available to players with certain 3D graphics cards, was another of his eureka moments. "As we worked on the project, 3D was really becoming a thing. It seemed like everybody was going 3D. I worried that the game would come out and look dated because it wasn't 3D, because 3D graphics had rapidly advanced over the course of the project."

A 3D graphics card was required to enable Diablo 2's Perspective Mode. (Lord of Destruction expansion shown.)

A solution occurred to him late one morning. Like the original game, Diablo IIunfolds on a grid, with one major difference. Each diamond-shaped tile is composed of several smaller diamond tiles that allow for some overlap. This meant that objects such as player-characters, monsters, treasure chests, and items can occupy the same squares on a grid by standing in smaller squares within each larger square, an impossibility in the first Diablo. A more granular layout facilitated Dave's pseudo-3D solution, which he called Perspective Mode.

His idea was to take the texture stored in every miniature tile and rotate it just a smidge, so that it wasn't quite orthogonal, as players moved around the screen. The game passed those textures to the video card, which painted them onto two polygons and then stretched them vertically and horizontally so that they appeared larger or smaller depending on the player-character's position. Trees and buildings, for example, seemed larger or smaller as players moved closer or further away, and scrolled by at a different speed than other objects in the foreground and background, creating a parallax effect. Objects shimmered slightly, the result of bilinear filtering, a process baked into graphics cards that smooths out textures when objects are rendered larger or smaller than their native resolutions.

Everything, from characters and items to structures such as the cabins and towers in Act I, expanded and shrank in Perspective Mode, an option only available to users running 3D cards that the game supported. "It was doing real, 3D math, and making this grid scale slightly, stretch slightly," Dave explained. "It gave a real sense of depth to the world."

In an impressively short span of time, Perspective Mode was finished and rolled into the latest build of the game. "There were a bunch of things I had to do to make sure walls lined up properly, and the lighting, but I think I wrote that fairly quickly," Dave continued. "I think it only took me a week or two to get it working. People loved the way it looked, and it really was awesome, but the artists weren't super happy they had to go back and chop up things and render them differently. We did feel it was worth it in the end, and added a lot to the game."

Other shower-time epiphanies were of the magnitude of seamless environments. One of the biggest knocks against Diablo was that the game's three character classes were no more than starting points. Players who chose a Warrior could cast spells by boosting his magic attribute, as Sorcerers could swing swords and fire arrows by upgrading strength and dexterity, respectively. That versatility had made Diablomore accessible, while at the same time rendering the player's choice of hero meaningless. Over time, the game's community pinpointed the Sorcerer as the best choice. His fast cast rate and higher maximum Magic attribute gave him access to the game's most advanced spells, especially one that let him use his pool of Mana energy as health. Because players who rolled a Sorcerer were practically guaranteed to have exponentially more Mana than health, they were nigh invincible, robbing the game of much of its tension.

"We wanted to put cooler stuff toward the bottom, so we'd say, 'Oh, yeah, that uh, that seems like a level-15 spell. Yeah."

To diversify Diablo II's heroes, its designers decided that each hero would have dozens of unique skills. The only question was how players should learn skills as they progressed. "I remember the shower where I had the idea," Dave said. "It just dawned on me one day: What if player classes could choose their skills, just choose a path through a tree?"

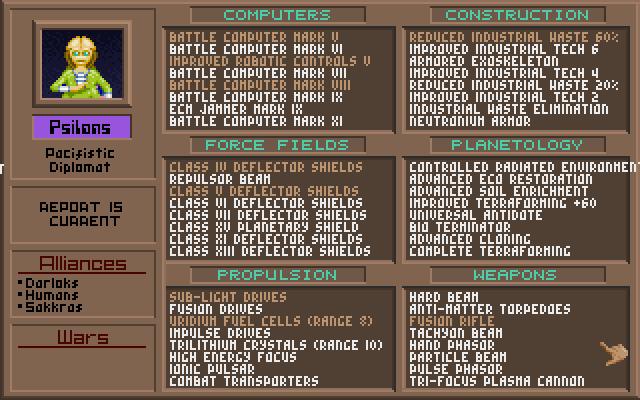

Dave loved to binge on games like Master of Orion, which hailed from the 4X strategy genre: Players eXplore environments, eXpand their influence by building new settlements, eXploit resources to purchase upgrades, and eXterminate any and all opposition. Master of Orionin particular gave players a deep research tree, a mechanic introduced in the board game Civilization by Francis Tresham4, which shares no design relation with Sid Meier's Civilization, the computer game widely credited with popularizing research trees in video and PC games.5The main thrust behind skill trees is organization. Upgrades are arranged in such a way as to communicate cause and effect to players: Buying one upgrade lets them learn a new skill, and unlocks more advanced upgrades that require players to learn earlier ones first.

Likewise,Diablo II's classes could have access to vast subsets of skills, divided into categories across separate skill trees. "I came into work and told it to Erich. I think this all was around the [development of] StarCraft," Dave said.

Research in Master of Orion.

Research in Master of Orion.

Dave wanted to hew close to Master of Orion by giving characters a tree composed of dozens of skills, perhaps as many as seventy. The resultant design would have been less a tree and more a snarl of branches that would have been too complicated for players to follow. Stieg Hedlund sanded down the idea's rough edges. "While I was taking a break from Diablo IIand working on polishing StarCraft, we [both Blizzards] made a tech-tree poster," Stieg recalled. "It was literally a tree in that it started at the bottom and involved the interdependencies of buildings and units."

StarCraft's tree poster was not represented in-game. Clicking a building or combat unit opened an interface consisting of icons, some highlighted, others grayed out. Highlighted icons were usable immediately, often at the cost of resources. Grayed-out icons were disabled, but players cou