This April, the War Robots project turns 10 years old. While a lot has changed over the years, our love for robots, combat mechs, exoskeletons, titanic fighting machines, and the like has remained the same. Just look at a snapshot of how many unique and cool robots and guns we’ve created during this time:

83 beautiful robots

15 amazing Titans

149 guns of an incredible assortment

Plus, a huge number of skins, remodels, modules, pilots, drones, ships, turrets, and “ultimate” versions of our content and maps

Hello! My name is Erik Paramonov, and I’m the Lead Game Designer at War Robots. In this article, I'll share a retrospective look at how our approach to robot design has evolved.

Of course, beyond robot design, there are many other different content layers in the project, but it’s the robots that are the soul of the game – and I can share a lot about them. Further, the other game content is developed in parallel, and in many ways along a similar path. So, in any case, the development of robot design will present the most complete representation of this path. Let’s kick things off by talking about visual design.

Our approach to visual design: the beginnings

A long time ago, our project was actually called “Walking War Robots”. It’s a good thing that we eventually abandoned that first word because it would be really difficult to explain why our “walking robots” can now run, fly, levitate (and even teleport).

If you were to look up old documentation, ancient GDDs, and already forgotten drafts, you would find several simple commandments for War Robot’s visual design during those times. We’ve already moved away from some of those, but back then, the gist was this:

Our robots are gigantic – 10 to 20 meters tall.

Since they are so enormous, they are also slow; this is logical, considering that they weigh hundreds and thousands of tons.

Our robots are military machines, and this should be conveyed by every detail: starting with references to real-life military equipment in the design of the models and ending with the fact that it cannot be painted in bright, cheerful colors.

War Robots takes place in the near future: by this time, military equipment has become more powerful, and new resources and energy carriers have appeared. This makes it possible to manufacture huge robots as a convenient and effective combat unit.

That said, now, ten years later, we’ve since reconsidered each of these rules, and content design has long moved away from old approaches – for good reason.

Experimenting with style

In the beginning, we had some restrictions regarding the overall design of robots (militarism, references to military equipment, a tendency towards realism), now we just try to comply with the framework established by technical restrictions, plus certain stylistic guidelines.

In the design of our first robots, you can easily notice the outlines of real military equipment. For example, the Griffin robot is clearly inspired by the British HP.80 Victor bomber, and the Leo robot, in both name and appearance, is a clear reference to the German Leopard tank.

HP.80 Victor bomber and Griffin

HP.80 Victor bomber and Griffin

Leopard tank and Leo

Leopard tank and Leo

Over time, we tried to move away from one particular style and look for something new. One of the first of these experiments was the “Knights of Camelot”: their body design already had anthropomorphic forms, but at the same time there were still touches of harsh militarism and realism.

Then, we gradually started trying new and completely non-standard solutions for the WR universe. Among these: experiments with color, body shapes, chassis types, both anthropomorphic and animalistic vibes, and the use of images from the culture and mythology of different regions and countries. Here are just a few examples of how robot design has changed over time:

These are the robots from 2016 to 2021. With just 4 examples, we see influences ranging from Battletech, to animalism, and even alien designs

These are the robots from 2016 to 2021. With just 4 examples, we see influences ranging from Battletech, to animalism, and even alien designs

Of course, you might wonder why we did all this and if we were concerned about losing our identity. After all, some players were probably attracted by the robots that look like military equipment in the first place – were they even going to be OK with these experiments? The answer is pretty simple: the design was adjusted to the gameplay, and was finally consolidated only after we saw that the players reacted positively, with growing metrics.

As time progressed, the new robots became faster and faster, and their abilities were much more complex than just jumping or activating a shield. The old design was rethought and adapted to the new gameplay, and the successful performance of these new robots (this success was measured by player interest and high marks within our in-studio content popularity charts) confirmed that we had chosen the right direction.

Maintaining our identity

As for the question of identity, our artists (and designers) do an excellent job of ensuring that, despite the uniqueness of each new piece of content, we maintain some kind of continuity. For example, in the picture below, there are robots from the same “family”, but which were created in different time periods; each looks unique, but still conveys some kind of relationship:

Cerberus (early 2020), Typhon (end of 2020) and Erebus (end of 2021)

Cerberus (early 2020), Typhon (end of 2020) and Erebus (end of 2021)

Upon adding the “Pilots” feature to the game in 2019, the lore of the WR universe began to develop: factions appeared — five megacorporations competing with each other, and these factions also help us maintain a sense of identity with our robots. Each of them has its own history, degree of influence on the world and, most importantly, style.

We collected five different styles, integrated them into the WR universe and formulated a set of guidelines: with these, we can make robots of various styles, while at the same time, maintaining the overall WR identity. For example, while robots from the DSC faction may look different when compared to one another, players will not confuse them with machines from the EvoLife faction.

As a result, the game does not suffer from visual stagnation, and we can also please both fans of militaristic Battletech, Gundam, or Evangelion, as well as other robots and mechs from popular universes – all while maintaining the visual identity of War Robots.

Image, name and gameplay synergy

We also have to keep in mind the context that this image lives within: War Robots is primarily a mobile midcore shooter, and our target audience, for the most part, doesn’t like overly complicated mechanics – they also value their time: make the user wait too long, or introduce an entry threshold for content that is too high, and you’ll quickly lose retention.

The same goes for ease of navigation. The player must understand what content they see even before they start playing with it — this is exactly where the synergy of image, naming and gameplay comes in. If you see a snow-white robot called Seraph, with pointed and aggressive design elements on the body, large cannons on the shoulders and wings with jet engines on the back – it’s not difficult to assume that, at a minimum, this robot can fly and probably has an aggressive nature.

Seraph

Seraph

Therefore, robot kinship can be clearly traced not only by their visual appearances (as demonstrated in the example above), but also by their names, and even their abilities. This is an important point that we always keep in mind when designing any piece of content: it seems obvious that image, abilities and naming should be in sync, but it is very easy to forget about it.

Further, selling an image is much easier than selling an idea. The latter still needs to be conveyed, explained and presented. But it’s enough to see the image, and the more holistic it is, the easier it is to interest the player with it.

As another note, over time, we have adopted the “Combo” system, kind of like a meal combo at a restaurant: this is when the robot always comes with the appropriate guns, a pilot and a drone. These additions not only support gameplay, they also perfectly complement the image. More on this a little later.

The general principles of interaction between art and design teams

We started with the fact that the art and game design departments were separate and interacted only as a performer with the customer. Game designers (GDs) prepared the documentation, collected references, finalized the image of the robot within the department, and transferred the documentation to the art department.

From there, the art department would read the documentation, prepare everything necessary for it, put the content through internal review, and after a few months, return to the game designers with a completely finished model with textures and animations. At this stage, the GDs could still ask to change something, but not radically, since the work was already considered completed.

This system was sorely lacking in flexibility, not to mention that closer collaboration between departments is always helpful. An idea or concept could be created by one person, then implemented by another, depending on workload – but this created inconsistencies.

Thus, over time we changed the pipeline. Now, each piece of content has its own GD, whose task is to work on this content from idea to release.

The first thing GD starts with is the concept; usually this is “cooked” within the GD department, but even at this stage the game designer begins to consult with the art department.

While the GD is thinking through the subtleties, a general description of the idea is transferred to the art department and work begins there. Throughout the process, everyone is constantly sharing their work with each other. Then, when the concept documentation is completed, the art department already has its own, which can be easily applied when writing full-fledged game design documentation (GDD). At this stage, the game designer tries to apply the ideas that the art department managed to translate in drafts.

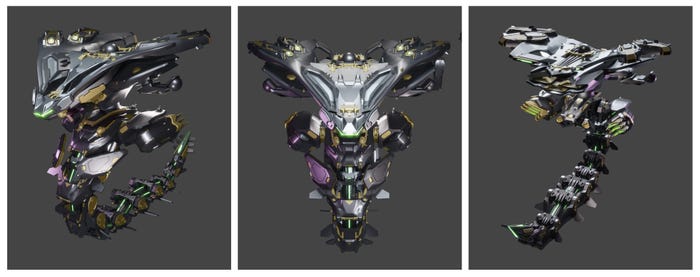

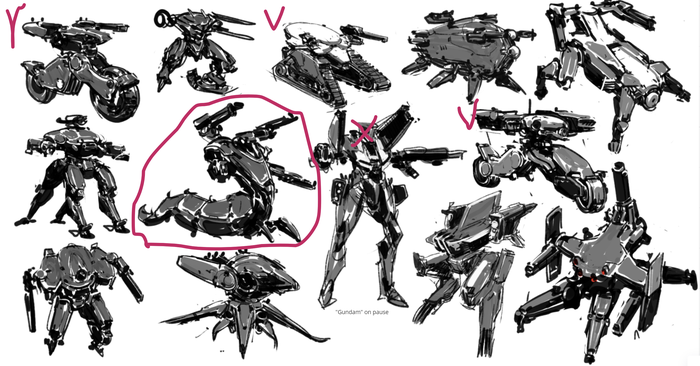

After writing the GDD, the departments start interacting more closely – the GD and art department constantly discuss developments and create the final image of the content. Here is an example of the process of working on one of the content units:

Stage 1. The art department generated ideas and forms, and GD identified the most interesting