Mike Stout (@MikeDodgerStout) is a veteran video game designer.

Whenever I try to write about training in video games, some kind of firestorm erupts around it. Inevitably every bad training segment, every inelegant technique, and every failed experiment is brought up as an example of why "training is bad, and I prefer to have my games with NO training, thank you very much!"

If you search tvtropes.org (a database of clichés found in pop-culture media) for the word "tutorial" it returns more than 10 different tropes surrounding things people hate about video game training. By comparison, I only found two articles about how much people hate downloadable content.

The saddest thing is this: That's not what I'm talking about when I write about training.

I can't have the conversations on training that I want to have with people because of this misperception.

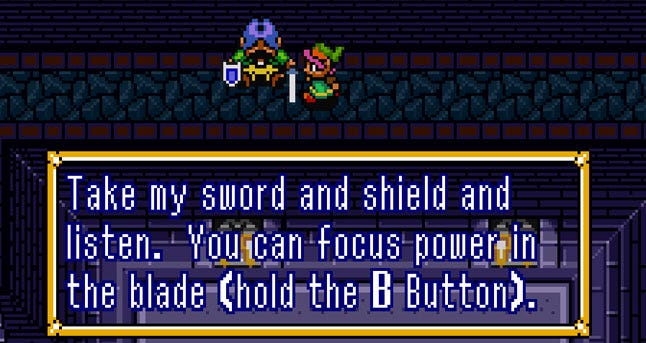

What I mean when I talk about video game training boils down to a really simple idea that I'm sure almost everyone has seen executed well in one or more great games: If you are very clever with your level design, you can train players on how to play the game by having them... play the game.

As I hope to show, this is not a particularly new or revolutionary way of looking at training. It's also not sexy and exciting, and when it is done well, a designer's best hope is that the player will not even notice that the training is there -- which is why you don't see a lot of people trying to talk about it.

However, when done poorly, training can be one of the worst things in a game.

RTFM?

Before I move on, I have to mention one of the oldest game training methods there is: The Manual. For those of you too young to remember, manuals were tiny paper booklets that came with a video game. These booklets were filled with pictures, seizure warnings, and (perhaps most importantly) how to play the game.

Manuals are a pretty good way of teaching people how to play your game, but they have some obvious downsides:

They rely on the ability to read, which isn't appropriate for all types of games or all audiences.

They can be easily lost (or not sold with a used game), which leaves your players without training at all.

They can fall victim to all the same problems that in-game training can. I elaborate on those problems a little later in this article.

They add a bunch of time from the point players buys your game to the point they actually start playing. Whether in a manual or in software form, this is not desirable.

Because of these and other weaknesses with instruction booklets, game designers started trying to put training directly into the game -- sometimes with more success than others.

Why do games even need training?

One thing that most games have in common is that they have rules; rules which define the bounds of the game, how it's scored, when it ends, and how the players all interact with the game and each other. If you gather a group of players to play hide-and-seek, you can't play until everyone knows who will be "IT," what the legal hiding locations are, how long the "IT" player has to count, and so forth.

If two players whip out a chess set, there can be no play unless both players know how the pieces move and what the winning conditions are. (Or whether or not you're using the "En passant" rule.)

What it comes down to is this: Somehow, the game's designer (the kid who comes up with the rules) has to explain those rules to players (the other kids).

If the first kid (the game designer) can't explain the rules, there will be no game. The first kid must train the others.

If the player doesn't know how to play your game, they CAN'T play your game.

Why do so many people think they hate training in video games?

The trail blazed by early designers is littered with the corpses of failed training experiments. Given how completely necessary it is for players to understand the rules of a game, a lot has to go wrong before teaching players how to play a game becomes intolerable to the players.

Here are a few very common (and completely reasonable) reasons I hear for why people hate training:

"Training wastes the player's time!"

Players are usually referring to incredibly long tutorials (some longer than six freaking hours), or that mandatory firing-range segment tacked onto the beginning of their favorite first person shooter. This is an immensely hate-able convention, so hating it is understandable -- it's just not what mean when I say "training."

"Training is forced on the player!"

This usually comes up when players describe a long list of un-skippable or otherwise incredibly annoying "help" that you must experience before you're allowed to play the game. This kind of thing isn't elegant or particularly player-friendly -- and it's also not what I'm talking about when I say "training."

"Training is boring!"

This exclamation usually precedes a list of forced tutorials that hold your hand step-by-step, not allowing you to learn anything on your own, explore the world outlined by the game's rules, or generally to… you know… play the game! It's even worse the second time you play, because you already know this crap and want to get to the good stuff! This is also not what I'm talking about.

"Training is insulting!"

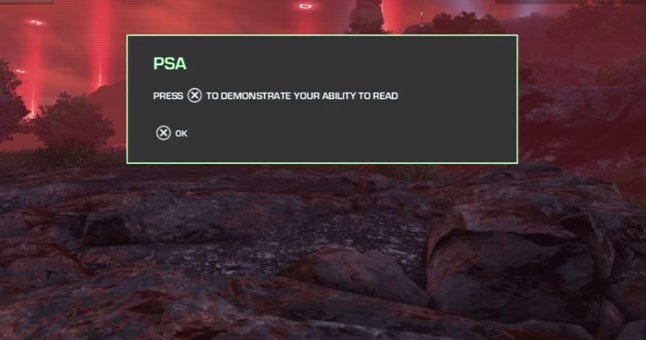

This is usually some kind of "do you want to switch to easy mode" BS. The tone of these kinds of tutorials is condescending or otherwise assumes the player is not a reasonable human being with a mind capable of discovery. The other common occurrence is the help text that arrives after you've already been doing something for a long time. For example: "Press A to jump!" for the 50th time.

This isn't what I'm talking about either.

Ah, the shooting range – where heroes are made, not born.

"Training is aesthetically inappropriate!"

Sometimes this is really obviously inappropriate -- like when your character is a bullet-spewing power fantasy and you have to start the game learning how to point and shoot a gun at a target. Sometimes it's less obvious, and only slows the game down or breaks the flow during a part of the game where the pace should be accelerating (a.k.a. the first level).

Nope, that's not what I mean either.

"Most of the time, training doesn't even work!"

This is usually in reference to a quick "flash up the controls screen one time and never again" sort of tutorial. Other times it's about how a game will train you on something in level 1, then not make you use it again until you've forgotten how it works.

"Wait… how do I do a long-jump again?"

As you probably guessed, this is also not what I'm talking about.

"I like exploring and discovering things for myself. I prefer games that leave me alone and give me space to do that."

This feeling of exploration and space to experiment is the end result of exactly what I mean when I talk about training. If you design your levels (or content) with training in mind, you can train players by letting them play the game.

“Are you sure you have a brain? Press X to confirm” (Tutorial Parody from Far Cry 3: Blood Dragon)

A very famous example

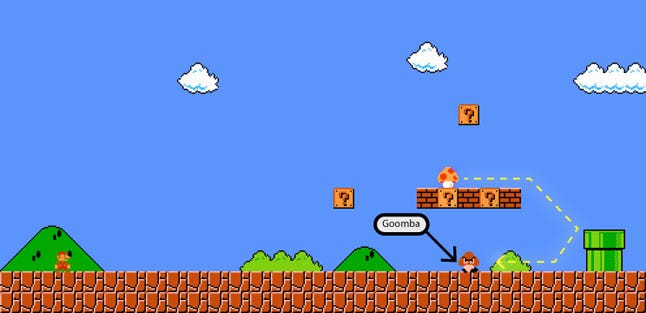

I want to share one of the most famous examples of this "in-gameplay" type of training: The first two screens of the original Super Mario Bros., for the NES.

In an episode of Iwata Asks, Nintendo CEO Satoru Iwata talks with Super Mario Bros.' designer, Shigeru Miyamoto about this first screen and all the "hidden" training built into its seemingly simple design:

On goombas:

No tags.