This is the fourth of six articles about the process of publishing PC games. We’ve already discussed in detail how Steam and third-party distribution work, whether or not there’s still life left in other open platforms, and how bundles and crowdfunding work. In this article we’re going to focus on an extremely narrow field: localization.

I feel like I should probably give you a brief explanation of why I consider myself qualified to write about localization. I first encountered commercial video game localization and adaptation in 2006. Since then, as a developer, I’ve had to integrate translations into PC, browser, and mobile games.

I’ve developed localization tools as a member of a publishing team (and as someone hell-bent on finding an alternative to Trados, which is crazy expensive). Two years ago I took a wrong turn and went down the rabbit hole of community-driven translation. Localizing large projects doesn’t instill horror in me, but it does make me shiver and grind my teeth.

What is localization?

The localization process is about a lot more than just translating a game’s text. It also involves quality assurance, testing the integration of the translated text into the game, and adapting the text to the requirements of specific regions. Here’s a rundown of the most important aspects of the localization process.

Translation: the translation of the game’s text and assets from one language into another. It can be performed by one or more people.

Editing: correcting stylistic and semantic errors, checking translation consistency, and making sure the terminology is correct and consistent.

Proofreading: correcting spelling errors and other typos. This step often involves working with the text alone rather than within the game.

Integration: integrating translated materials into the game, changing and adjusting the UI/UX to make sure everything displays correctly, and tweaking the code a little to add the translated materials to the game.

Regional adaptation: in China, for example, you can’t show blood, skulls, or any religious symbolism in games. Korea frowns on playing around with religious themes. In Australia you need to remove all alcohol and drugs from your game.

Linguistic quality assurance (LQA): testing the quality of the translation and its integration into the game.

And don’t forget about marketing materials. This is just one more aspect of localization that will have to be performed for every market the game will be released in.

Processes

Before we whip out our calculators, let’s take a couple of paragraphs to deal with the localization process itself and the aspects of it that you need to pay attention to regardless of whether you’re a developer or a project manager.

I had to write and do all the calculations sober this time, so the article came out super-serious.

If we’re talking about a game with 10,000 words, localization isn’t going to be all that big a deal, but if you’ve got a big game with 100,000–300,000 words, failing to understand processes and tools properly will result in a huge headache. Translators often don’t know how the text they’re translating is going to look once it’s in the game.

If the translator can’t understand the logical connection between certain parts of the lockit (localization kit) such as, say, an item’s name and its description or the name of a quest and its explanation, this can lead to a plethora of errors. The result is a huge expenditure of time and resources (time spent finding, reporting, fixing, and verifying mistakes).

Engine readiness. You need to be able to display UTF-8/16 characters, use sprite sheets for fonts, and have the tools to create character kits for sprite sheets (especially for languages that use logograms—you’ll need at least an 8K texture for every 12 point character just to cram all those Chinese guys in there).

Once you’ve used Google Sheets to export text and import it back into the engine it can be very hard to force yourself to switch to other formats. Some localization platforms can update the text in real time. This is very convenient, especially if you’re working on a mobile project. It’s a very important and useful feature.

Fonts. Licensing aside, you have to ask yourself whether the fonts you’ve chosen can display all the characters you need, including Latin and Cyrillic letters, umlauts for Romance and Germanic languages, etc. You’ll probably have to start using separate groups of fonts for Chinese, Korean, and Japanese.

Decide how you’re going to deliver the translation to the user. Will you include all available languages in the game or use separate language packs as DLC for every specific language?

Start by breaking any groups of visual elements into subgroups. This includes headings and subheadings, basic and additional blocks of text, navigation elements, and so on. At the very least you’ll need to be able to flexibly configure font sizes, adjust line and character intervals, and change the baseline font.

Make sure you have the necessary tools or understand how non-textual assets (images, sounds, models) will be localized. You want your tools, engine, or library to be able to do this without any additional effort on your part.

You’ll also need to decide if you’re ready and willing to deal with recording dialogue and phrases in other languages. The price will be sky-high, at least when compared to the cost of translation alone, and there will be a heap of new technical problems. However, it will also immediately bring the quality of your localization to the next level.

How are we gonna do this?

Keep in mind that the translation you’re doing isn’t static. Your game will evolve. You’ll release DLC, change things, add things, etc. Some parts will end up being translated again. Think about how you’re going to do all of this at the very beginning of the development process. There are at least three approaches, each with its own pros and cons. The diagrams below show examples of each of them.

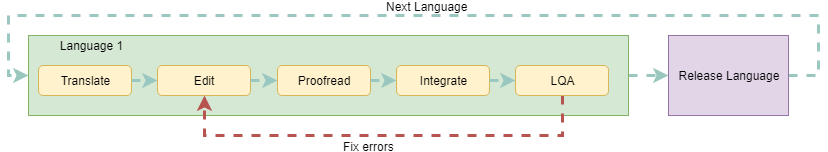

Successive. As long as the number of words in your lockit doesn’t exceed 10,000 you can safely ignore any difficulties and localize the game one language at a time. The downside to this approach is that it takes longer. The more languages there are, the more time you’ll spend translating. The upside is its simplicity.

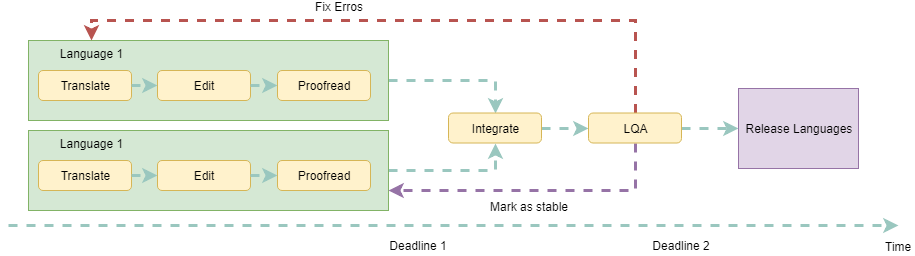

Parallel. This approach is typical for larger projects that require a large number of languages to be ready by a specific date. It involves translating the game’s text from one primary language into many others. Once the primary language is finalized, you start translating the text into all the other languages at the same time. This is followed by general integration and LQA. The downside of this approach is that LQA and making changes are very expensive. The upside is speed, which is achieved at the cost of increasing the complexity of your workflow, especially if you have multiple contractors.

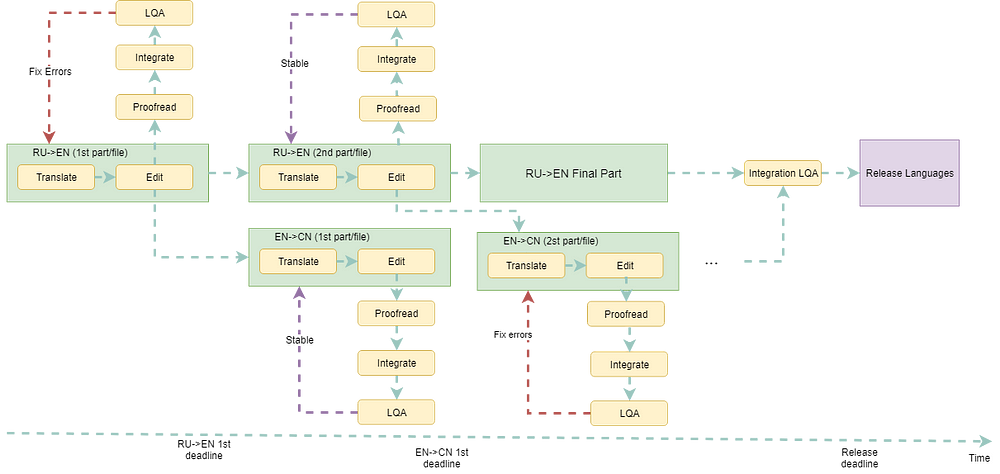

Cascade. This is a hybrid of the first two methods. As soon as the individual parts of the text (chapters or UI categories, for example) are ready and stabilized, you send them out for translation one by one. Individual blocks of text can be translated and integrated more quickly than the entire game in toto. This approach is ideal if you use several primary languages or if you’re translating consecutively between language pairs—for example, from Russian into English, then from English into Spanish and Italian, and then from Spanish into Portuguese. The upside is speed and only slightly higher cost. The downside is that it makes project management more complicated.

Tools

The right translation management tool (Computer-Assisted Translation or CAT) will save you a bunch of stress, time, and money. In addition to helping you work efficiently and correctly, it will also allow you to understand the performance of the individuals or team working on the project and correctly estimate its timeframe.

Translation memory (TM). This is a key technology for modern translation projects. The purpose of TM software isn’t so much to save time as it is to reduce cost and improve quality. Neither you nor your translators should waste time translating identical bits of text over and over again. The same source text in the same context should always be translated the same way. The need to change translation keys (but not the text) shouldn’t be a problem. We’ll talk about fuzzy matches a little later—this is something you just can’t do with without a TM. My latest localization experience shows a 5.1% savings thanks to our use of a TM. Localization managers I know personally have told me that TM software could save you up to 25%—30% on large MMOs.

Repetitions. The number of repetitions can easily reach 30%—40% in a large game. With proper text processing prior to translation this can be increased to 50%—60% of the entire text. Case in point: we’re currently translating an MMO into English, and the original word count was about 300,000 words. Proper memoQ settings reduced the word count to about 245,000 words after factoring out repetitions. That’s a savings of about 20%, or $6,500.

Proofreading tools. These tools can help you perform simple filtering, tagging, and analysis of text and keys that have already been validated. Knowing which keys are validated is critically important if several people are working on the translation.

Change management (fuzzy). These tools mark and filter text and keys that have been changed in the source language and let you make changes to the target language. Imagine that a line has been changed just a little or that a word has been added to a sentence. You don’t want to pay to have the entire sentence re-translated, do you? Moreover, small stylistic changes in the source language often don’t require retranslation in other lang