Here I share some thoughts on how game design practice has been shaped by business, technology and culture. First published in the book Critical Hits: An Indie Gaming Anthology, edited by Zoe Jellicoe, foreword by Cara Ellison. Available for purchase here.

In 1884, an English man called George Sturt inherited a two-hundred-year-old wheelwright’s shop from his father. A wheelwright was an artisan who made wheels for horse-drawn vehicles — carts and carriages. Sturt had been a schoolteacher, and was entirely new to this business of making wheels. As a man possessed of both a wheelwright’s shop and the enquiring mind of a scholar, Sturt set out to learn not only how wheels were made, but also why they were made that way. Finding people to show him the wheel designs and how they were constructed was not difficult. But he could not find anyone to explain why, for example, cart wheels were a strange, elaborate dish-shape — like saucers. Why were they not flat? At first glance the strange shape seemed to have some clear disadvantages. Not only did it make them more time-consuming to build, they had to be positioned on a cart in such a way as they jutted out from the side at a rather odd angle. And yet they did their job remarkably well.

Sturt developed his own theories to explain the strange design, which he recorded in his 1923 book The Wheelwright’s Shop, and in the decades since then designers and engineers offered their own theories. While Sturt was destined to never truly understand the secret logic encoded in this wheel design, he quite happily continued using it to make wheels over a number of years. In doing so he was following the tradition of generations of wheelwrights before him, whose knowledge and skill were accompanied by that other enduring tradition of the artisan: an almost complete lack of theoretical understanding.

Turn-of-the-century game development

We no longer have wheelwrights and we are no longer making wheels in shapes we don’t understand. This is because design practice (the way designers design) in any discipline — from the creation of wheels, buildings and furniture through to film, music and literature — develops over time. It reaches milestones; it passes through phases. Until around a decade ago videogame design looked as if it was about to begin the evolutionary shift that other design disciplines had made before it. But this did not happen. A confluence of major changes to the world of videogames — technological, industrial and cultural — took place, setting game design on a very different course. To understand what happened, we need to turn the clock back to the late 1990s and early-to-mid 2000s, before these major changes had occurred.

Let’s imagine a console game (for PlayStation or Xbox, for example) being made in an averagely successful game development studio.

Game design would usually kick off with a pitch for a game idea, taking the form of a document, some concept art and perhaps even a video mock-up or prototype. This pitch (and some business due diligence) was usually enough for a publisher to decide whether the game was worth financing. Once the project was green-lit, the first phase of development, ‘pre-production’, would begin, and a small team of designers would produce a several-hundred page game design document. This document was used as a blueprint for the production of the game and project planning; that is, for breaking down the elements of the game so that they could be costed and scheduled, and as a means of communicating all the elements of the design to the publisher so they knew what they were getting. A prototype, or perhaps more than one prototype, was then produced.

Based on this prototype and the, by now hefty, design document the game would go into development for the next year and a half or more, with a team of several to several dozen, or even hundreds, of game developers.

Many months or years into this process, the project reached the milestone known as ‘alpha’, meaning that the game was considered to be ‘feature complete’. All major functionality would have then been implemented, and the game was playable from beginning to end. It was often not until this point that designers could playtest and evaluate their game design. Frequently, the gameplay would require some major changes.

Design changes mid-project could send development into disarray. Project managers were naturally wary of any changes that would result in having to throw away months of production work. Besides, the project may at this point already be running late, and some features were already being cut from the game, leading designers to despair. Programmers were now working weekends and nights, for months on end. Occasionally, after months or even years of work, the now fully-playable game might reveal itself to be so irretrievably bad that the publisher would cancel the project altogether and cut their losses.

This process that I have just described — the process being used for most game development projects at the turn of the 21st century — was beginning to stagger under its own weight. Ploughing significant resources into a game months before you could be fully confident that the game design was not fundamentally flawed was risky. As teams grew and development budgets rose from millions to tens of millions, publishers became wary of backing projects that took creative risks. It was safest to make games with the kind of mechanics that we already knew worked — because we’d already played them in other games. Innovation, many observed, was suffering as a result.

Things going awry in Game Dev Story (2010), a game development studio simulation game.

Things going awry in Game Dev Story (2010), a game development studio simulation game.

Considering the relationship between design and production

At the core of the problem was a conflict of interest between the increasingly demanding needs of production and the needs of design — it was a broken relationship. But game designers were not the first designers to find themselves needing to rethink the relationship between designing and making.

In comparing traditional building design to modern architecture in his 1964 book Notes on the Synthesis of Form, Christopher Alexander makes a distinction between two kinds of design cultures: ‘unselfconscious design’ and ‘self-conscious design’. ‘Unselfconscious design’ (or ‘craft-based’ design) concerns the use of traditional building methods, in which the designer works directly on the form (so, if you were a wheelwright, the wheel) unselfconsciously, through a complex two-directional interaction between the context and the form, in the world itself. The design rules and solutions are largely unwritten, and are learnt informally. The same form is made over and over again with no need to question why; designers need only learn the patterns. They know that a specific design element is good, but they do not need to understand why it is good.

They know that a specific design element is good, but they do not need to understand why it is good.

Igloos are a good example of unselfconscious design.

Igloos are a good example of unselfconscious design.

In unselfconscious design, design traditions and conventions stand in place of design theory. With no understanding of underlying design principles, modifications to, or removal of, a design element can be risky. This means that patterns and rules of design evolve very slowly. And while rules and conventions can develop gradually over time to attain a high level of design sophistication, as it did with the cartwheel, this is not accompanied with a deepening understanding and sophistication in the design principles that govern the patterns and rules.

Modern designers of wheels are not like their unselfconscious designer predecessors, the wheelwrights. They practice what Alexander calls ‘selfconscious design’. In this modern design culture, design thinking is freed from its reliance on making. Thanks to their design thinking methods and tools, an engineer or an architect does not need to build the bridge or house they are designing in order to test whether it will fall down. In the worlds of architecture and design this not only opened up possibilities for bold creativity and innovation, it facilitated the rapid adaptation of designs to changing social, technological and environmental requirements and fashions. Self-conscious design runs right through the arts as well. Consider a composer’s ability to write pages of orchestral music at a desk, without needing to literally hear the music they are writing.

In 2004, game designer Ben Cousins used Alexander’s distinction between traditional and modern design practices to criticise the videogame design and development process of the time. In a short blog post, Cousins suggested that game developers are still operating under an unselfconscious system of design. He described a game design culture that was rife with anti-intellectualism, where the ‘elders of game development’ were intolerant of any deviation from traditional process, and where ‘academic, scientific and analytical techniques are not allowed’, delaying ‘the search for true knowledge’. He argued that the major difference between designers in other media and those in games was the fact that we had not yet progressed to self-conscious design.

The call for game design tools

Cousins was not alone in this observation. It had not gone unnoticed that, despite the rapidly increasing technical sophistication and production values of videogames being produced, game design itself remained relatively under-developed. Back in 1999, designer Doug Church had published an influential piece in the industry’s trade magazine Game Developer, calling for the game design community to develop what he called ‘formal, abstract design tools’. Church warned that our lack of formal design understanding would hinder our ability to pass down and build upon current design knowledge, and that our lack of even a common design vocabulary was ‘the primary inhibitor of design evolution’.

In the years that followed, others joined the call. Designer Raph Koster highlighted the imprecision of natural language as a tool for designing gameplay, and proposed we develop a graphical notation system for game design. Designer Dan Cook went so far as to call past game design achievements ‘accidental successes’. Cook’s observation that ‘we currently build games through habit, guesswork and slavish devotion to pre-existing form’ is an apposite description of how unselfconscious designers work.

As Alexander explained it, an unselfconscious designer has no choice but to think while building — they design by making. But in self-conscious design, a designer has ways to solve their design problems without relying on making, or having to think through all the moving parts of a design problem just in their head.

To some extent, writing down ideas to think them through can help (such as in a game design document), but game designers were finding this process woefully inadequate. What self-conscious designers have that we did not was a means of ‘design drawing’. Design drawing does not literally mean a drawing; it could be a sketch or model of a building, musical notation or indeed any kind of material that gives a useful representation of the current state of your design thinking (your ‘design situation’). Design drawing is not primarily for communicating the design to other people — it is part of the design thinking process. You, the designer, can engage in a private design ‘conversation’ between you and these ‘materials of design’ that you are creating and modifying.

Design drawing is a designer’s superpower. In his book How Designers Think, Bryan Lawson describes how the advent of design drawing liberated designers’ creative imagination ‘in a revolutionary way’. It afforded them a greater perceptual span, enabling them to make more fundamental changes and innovations within one design than was possible in traditional design-by-making style practice.

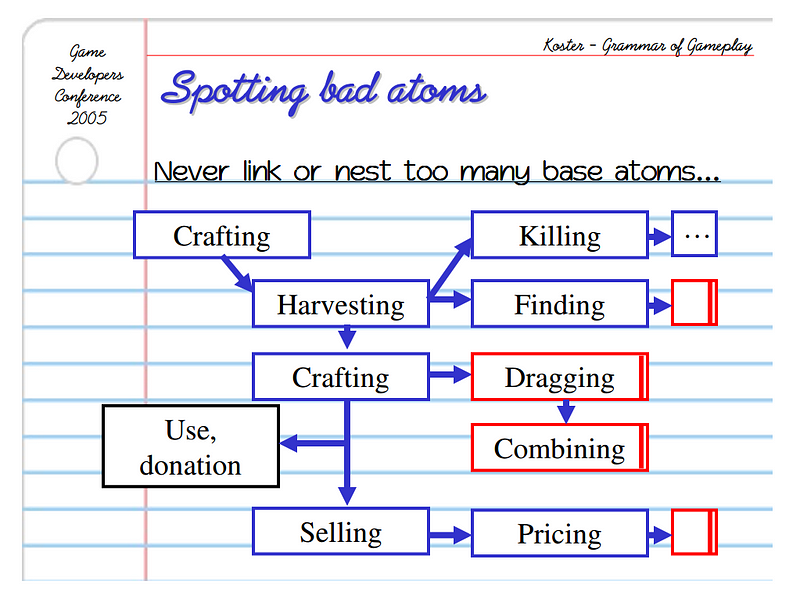

Some game designers and academic researchers began to see if they could answer Church’s call for design tools. They proposed ideas for developing semi-formal, sometimes graphical methods of modelling and describing gameplay. There were game designers who were trying to work out how to devise a kind of ‘grammar’ of gameplay that could help us break it down into basic units (‘verbs’, ‘ludemes’, ‘atoms’, ‘choice molecules’ and ‘skill atoms’). Others were attempting to abstract and formalise cross-genre design concepts, giving design talks with names like Orthogonal Unit Design. Project Horseshoe, an invite-only annual event ‘dedicated to solving current problems in game design’ that gathers some of the community’s most well-known figures, set themselves the task of figuring some of this stuff out.

A slide from Raph Koster’s Game Developers Conference talk from 2005, “A Grammar of Gameplay”

A slide from Raph Koster’s Game Developers Conference talk from 2005, “A Grammar of Gameplay”

Did these early attempts build momentum and grow into an industry-wide shift towards self-conscious design in games?

No, they did not. Game design today is not a self-conscious practice in which designers use design drawing tools to support their design thinking as an alternative to design-by-making. No language of game design, nor anything that could be described as ‘formal, abstract design tools’, has been adopted into mainstream game design practice. In fact, in game design today the make-and-test design approach of unselfconscious design has become even further entrenched. But with no adoption of new ways to better support design thinking that didn’t involve making, how did our increasingly unwieldy and expensive process of design guesswork not eventually fall over from its own weight?

This is because, in the last ten years, some major changes occurred that have, at least temporarily, delayed or masked the need for a shift towards self-conscious design. These changes have allowed us to mitigate some of the inefficiencies and slow-paced evolution of unself-conscious design by driving a huge increase in the speed, volume and sophistication of both making and testing. If we were wheelwrights, this would be akin to having a phenomenal capacity to build wheels and test incremental adjustments to them, on a massive scale at high velocity. In other words, we now engage in a kind of ‘brute-force’ unselfconscious design practice, where our design evolution and innovation has come to rely less upon any advancement in our theoretical understanding and sophistication as designers, and more on our sophistication as makers.

The influence of the software industry

The first major change to the way we make games came from outside the game industry — via the software industry.

Let's once more review the state of the game development as it was in the early years of this century. Many people felt that the way we made games was fundamentally broken. Game development projects were struggling, producing job instability, scheduling blow-outs, a 95% marketplace failure rate and a work culture of long hours so notorious it was making headlines in the mainstream press.

The fact that game industry project managers were usually young and lacking in formal training was undoubtedly a factor. But even the best software development project managers might have struggled with the process being used in game development at the time. This stage-based process that I described earlier took its cue from conventional software development processes that involved comprehensive planning at the beginning stage of the project — the ‘Waterfall’ model. Team members were required to understand and predict how long it would take them to solve a design or engineering problem before they had started working on it.

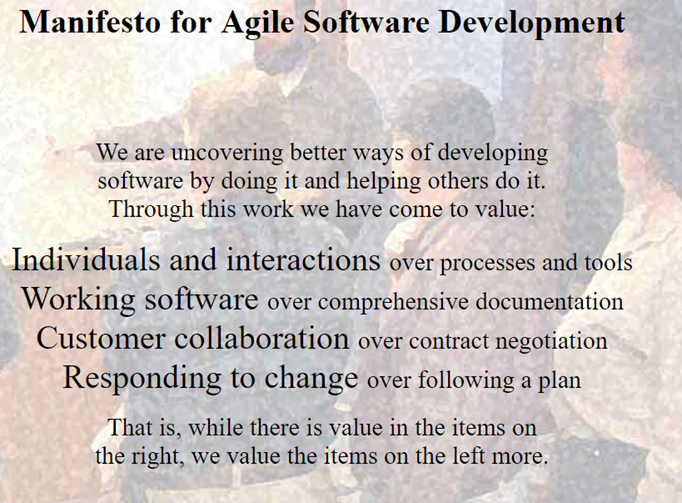

Critics of this process within the wider software industry were beginning to call this absurd and impossible, the cause of scheduling blowouts and other project management issues. Core to the range of new ‘agile’ software development frameworks that emerged in response was to replace elaborate planning and extensive documentation with the rapid, iterative creation of ‘working software’ so that it could be tested as often as possible, modified as needed for a new version, then tested again. This could be distilled into ‘iterate and test’. Make it, test it, change it, repeat.

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that when agile development became fashionable within the software industry, game developers — and designers — were enthused about this new iterative approach. Not only did it offer an escape route out of our development cycle of pain, it put playable versions of the game into the hands of designers right the way through the production cycle — a far cry from having to wait months for the alpha. Some game designers saw this as the salvation they had been waiting for: finally, hands-on creative control over a process they had seen gradually slipping away from them.

The Agile Manifesto (2001). Not only did it teach us to embrace iterative development, it also served as an alarming reminder of why you should never leave a programmer alone in a room with a Photoshop filter.

The Agile Manifesto (2001). Not only did it teach us to embrace iterative development, it also served as an alarming reminder of why you should never leave a programmer alone in a room with a Photoshop filter.

Production is transformed

But this could only partially address the increasing costs and time spent on producing something playable. In the early years of this