March of 1996. It was a turbulent time for Nintendo. After a huge rift in partnership, Sony had released its PlayStation six months prior. With the advent of new hardware, 3D polygon games had taken the world by storm. To catch up, Nintendo was ramping up to release its new 64-bit console in June of that year. Major game developers were preparing as well, opting to build games for the bigger, better Nintendo 64 over the now-aging Super Famicom.

It was already way past the golden age of 16-bit gaming, and the 3D era was knocking at the door:

Above: This is what Kirby Super Star was going up against. All of the listed dates are the initial Japanese launch dates for the games/hardware.

Above: This is what Kirby Super Star was going up against. All of the listed dates are the initial Japanese launch dates for the games/hardware.

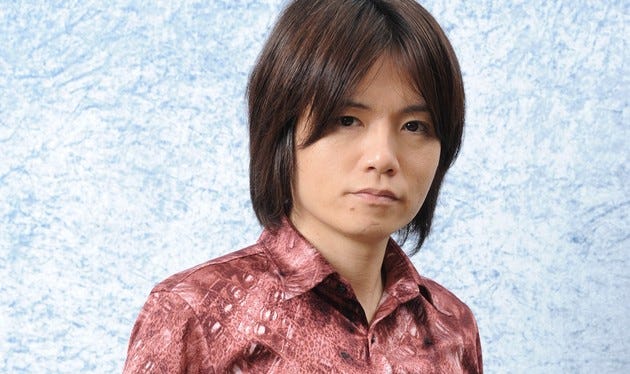

Knowing this, a young game designer at HAL Laboratory, decided to release a Super Famicom game named Kirby Super Star. And as if it were some miracle, amidst all the turbulence, uncertainty and increasing pressure, he managed to create one of the best Super Famicom games ever made. [1] [2]

Bounded Creativity

Kirby. Super Smash Bros.

What do these two video game series have in common? Other than being household names within the Nintendo-brand, they also happen to be the brainchild of game designer Masahiro Sakurai.

Having joined HAL Laboratory as a game designer straight out of high school, Sakurai’s first project was directing Kirby’s Dreamland for the Game Boy, released in 1992. Intended to be a placeholder character, Kirby ended up being loved by the designers to the point where they decided to keep him in the final version. On top of the unusual design, the game boasted a new style of gameplay not seen in the past, and it became an instant classic and was HAL’s most successful game at the time. Sakurai followed up with Kirby’s Adventure for the Famicom in 1993 [3], and it was met with even greater acclaim. Only in his 20s, he was already working with other industry greats such as Shigeru Miyamoto and the late Satoru Iwata.

But even at an early part of his career, he felt shackled by previous successes and the looming pressure of creating sequels over trying out original ideas. Quoting a translated interview with him from Nintendo Dream in 2003:

“It was tough for me to see that every time I made a new game, people automatically assumed that a sequel was coming. Even if it’s a sequel, lots of people have to give their all to make a game, but some people think the sequel process happens naturally.”

Although the quote was from long after the release of Kirby Super Star, you could have guessed his frustrations starting after the release of Kirby’s Adventure: many games in the Kirby series were beginning to be distributed among HAL Laboratory. While he was working on Kirby’s Pinball Land (1993) and Kirby’s Block Ball (1995), Sakurai was completely hands-off with Kirby’s Dream Course (1994), Kirby’s Avalanche (1995), and Kirby’s Dreamland 2 (1995). Even with a reduced workload, he still had no creative outlet to try something else.

Even before Kirby turned five years old, he had an impressive seven games under his name. I believe that Sakurai was getting sick of directing Kirby games at this point, and intended Kirby Super Star to be his swan song from the series [4]. And oh, what a swan song it was.

Back to the Basics

The Kirby series had already been turned into an experimental ground for HAL [5], with the pink puff-ball exploring a diverse genre of games: Pinball, Golf, Puyo-Puyo, and Breakout. But with his (presumed) finale for the series, Sakurai wanted to bring the game back to its roots: a charming, eccentric platformer.

Sakurai has mentioned the importance of a “fun core” in games [6]:

“There are all kinds of game genres, like fighting games and puzzle games, and each one has its own ‘fun core.’ First, I try taking away everything unnecessary around that core. Then, it’s like I place the fun core somewhere else and build around it again.”

And by taking the reins back for his creation, he was able to accomplish what he set out to do.

Above: Box arts for North America, Japan, and Europe, respectively. Kirby has always had a tradition of having distinct artwork between regions [7]

Above: Box arts for North America, Japan, and Europe, respectively. Kirby has always had a tradition of having distinct artwork between regions [7]

Kirby Super Star (renamed as Kirby’s Fun Pak in Europe) released on March 21, 1996, in Japan to once again, a critical success. In North America and Europe, the box art had a large banner boasting the cartridge contained “8 games in one!”. Although it is debatable whether or not all the games could be classified as “games,” it brought something that we haven’t seen before along with its “Sakurai-feel” that we all know and love today.

As soon as you booted up the game and got past the file selection screen, you were presented with a corkboard with an almost postcard-like selection of the games. Five of these were distinct platforming adventures, while the remaining three served as short mini-games that provided a break. A stark contrast to the games of that time that preferred narrative, theatrical experiences (look at the games that were released before on the timeline), Kirby Super Star presented itself through jam-packed, bite-sized sessions.

The game isn’t without a story; each sub-game has an optional intro cutscene that provides the minimal backstory of how Kirby got himself into the situation. It’s not much, but enough to give it the Nintendo-vibe.

It should be noted that some of the games are locked, only becoming available once you beat previous games. Although this gives the impression that the player can play in any order they want, there is a free ordering that most players follow based on the difficulty of the games. On top of the difficulty ramp-ups, each game chains together to create a coherent “meta-story” for the collection itself.

The Original HD Remaster

It feels like we’re in an era where remasters/ports/re-releases of games are prevalent, but it’s interesting to note that this is not a new thing. Nintendo has been doing this since the Gameboy era, and the Kirby series, in particular, has seen many remasters in its lifetime. [8]

Above: All intro cut scenes were faithfully recreated.

Above: All intro cut scenes were faithfully recreated.

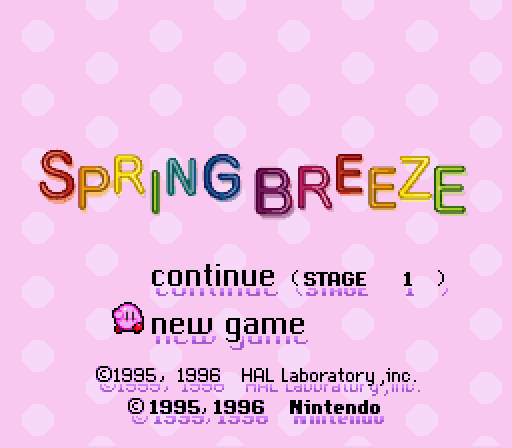

The reason I bring this up is that of Spring Breeze, the easiest sub-game happens to be a complete remaster of Sakurai’s debut, Kirby’s Dreamland. [9] Now featuring full-color graphics and a revamped soundtrack, it also serves as an educational ground for some of the new gameplay features that were added in Kirby Super Star. [10]

The most significant change was the fact Kirby’s Dreamland didn’t have copy abilities (that was introduced in Kirby’s Adventure), and Spring Breeze did. This fundamentally changed the core game. Even graphically, this was the first time that Kirby looked different in-game depending on which ability he possessed (through the use of ability hats); in the past, there would only be a visual indication in the UI.

Above: The sprite set collection used for the UI in Kirby Super Star. These comprise of the abilities you can obtain along with the helper for each (explained below)… And King Dedede

Above: The sprite set collection used for the UI in Kirby Super Star. These comprise of the abilities you can obtain along with the helper for each (explained below)… And King Dedede

There were other differences as well. Some of the changes served as quality-of-life tweaks: such as the jump button now allowing you to float instead of having to press up. The physics were tweaked a bit to make the controls feel tighter and less floaty.