If you work in or around some kind of software development, you’ve probably heard “MVP” sputtered in passing conversation, or seen it scribbled in a comment of a Google Doc. “MVP” is an acronym for “Minimum Viable Product.” The definition of an MVP is a loaded one, and changes slightly from Product Person™ to Product Person™. One popular definition is, “What can we build that will give us the most validation?” The school of thought I personally subscribe to (and will be using for the duration of this article) describes an MVP as “the smallest solution you build that will bring the most value to your customers.”

At first, all of this probably sounds straightforward enough, but there’s deceivingly a lot to unpack here; in my experience it’s never just “what’s the smallest solution.” In one of my favorite articles about MVPs, they say, “Starting with a solution is like building a key without a door” (9). It’s easy to fall into a cycle of Build/Measure/Learn (as the first definition I mentioned often teaches), but the issue there can be if you start with a bad idea, all you learn is that your idea is bad. There’s no room for iteration, and you’re essentially stuck.

How do you avoid starting with a bad idea? You start with understanding what problem you want to solve. Once you have an understanding of your customer base and the problem you want to address, you can narrow down on what kind of solution could be the best approach. After sending this solution out into the wild, you gather feedback from your customers, which you can use to iterate on the next version of your product.

In my personal opinion (and I just know somebody is going to start a fight with me about this), arguably the most important word in MVP is the “M”: minimum. The amount of work you put into an MVP is critical for many reasons, some big ones being:

Development costs money

Meetings cost money

Time in general costs money

EVERYTHING COSTS MONEY*

*Product Managers can’t help but see dollar signs attached to everything they see. This is a side effect from the Product Manager Initiation of looking into the mirror of a dark bathroom and saying “prioritize the backlog” three times.

In my experience, in the beginning you have the most control of “minimum”; it’s flexible, it saves you time (and therefore money), and it gives your “viable” room to grow and change as much as you need.

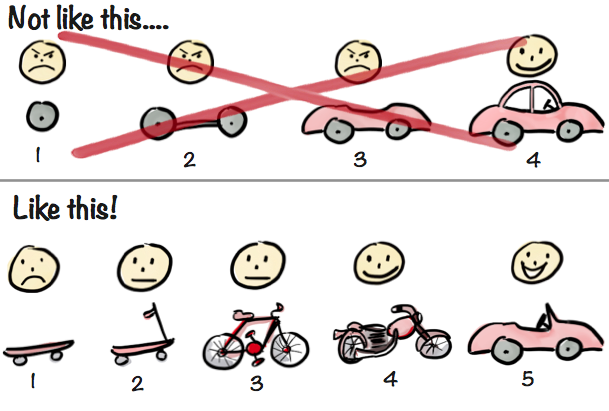

A very popular visualization of the MVP has been scurrying about the internet for a few years now, which you may have seen in passing, or even taped up on a wall somewhere in your office:

Source: “Making Sense of MVP” (which is a great blog I recommend if you just can’t get enough of MVPs)

Source: “Making Sense of MVP” (which is a great blog I recommend if you just can’t get enough of MVPs)

If you want my personal opinion (and I assume you do—otherwise you wouldn’t be here reading an article I wrote), this diagram is fine if you’d like to explain what an MVP is to your drunk uncle at Thanksgiving (or perhaps a drunk stakeholder at the holiday party), but I find it to be slightly confusing and misleading in practice. The spirit of it I agree with—start with a simple solution people like and iterate until they love it. It’s the execution, or rather, the items being used as examples that I severely disagree with.

I’d like to take a moment to explain what I mean. A skateboard, a scooter, a bicycle, a motorcycle and a car may be used for similar things (transportation for example, or perhaps some kind of strange illegal street racing situation), but by different people in different market segments, for very different kindsof transportation (or illegal street racing). Just because all of those things have wheels doesn’t mean they’re iterations of each other. Some of the transitions are more believable—skateboard to scooter? Fine, I’ll buy that. But scooter to bike is a pretty big product shift, as is motorcycle to car (both of which have got to be expensive in terms of manufacturing costs). Keep an eye out if your product starts to pivot that hard—it may be time to have a heart to heart with your team about your vision and alignment, and if you trulyunderstand the problem you are trying to solve and the people you’re solving it for.

Please note: Sometimes pivots are necessary because the market is always changing, but it can also be expensive. (“EVERYTHING IS MONEY!” some poor product manager wails as they flip a table and run into the night, screaming.) If you pour a bunch of time into one product only to chuck it out the window when it doesn’t work and go in a new direction, you just wasted a ton of money on something you probably could have learned through prototyping, the more forgiving cousin of Minimum Viable Products.

Related reading: What’s the difference between a prototype and an MVP?

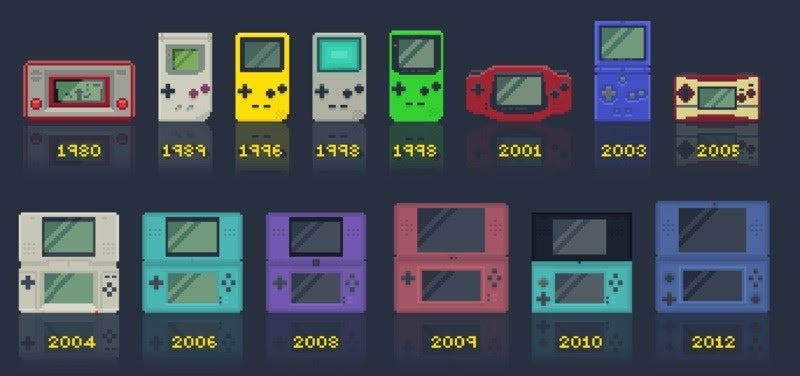

Since the above diagram causes me severe emotional distress, I offer instead an example of MVP progression I think is near perfection in terms of both vision and execution—Nintendo’s handheld gaming timeline:

*Chef kiss*. Source: History of Nintendo Gameboy

*Chef kiss*. Source: History of Nintendo Gameboy

No hard pivots here, folks. Instead when you look at their product progression you’ll see that the iterations are gradual, and if you take time to learn the context behind those iterations you’d learn they were also intentional. Nintendo knows the way to my heart, and it is through intentional design. Also, Pokémon.

In this article, I’m going to focus on the context behind the MVP for Nintendo that started it all for their handheld journey: the Game & Watch system. One can learn a lot from Nintendo in general, but in this article specifically we’ll learn about how they discovered a problem their customers had, the MVP they created to solve that problem, and how they iterated on that MVP through feedback and intentional design. I encourage taking periodic breaks to play your favorite Nintendo handheld, as nostalgia throughout this article is unavoidable (and dare I say it—intentional).

Nintendo, a real MVP of MVPs

It’s safe to say that a vast majority of people on this planet are familiar with the Nintendo Game Boy and its successors, but the same cannot be said about its predecessor, the Game & Watch, for two likely reasons. First, it’s more than 30 years old (and most of us can’t remember what we wore yesterday, let alone what happened 30 years ago), and second, the Game Boy was such a bonkers runaway success it kind of overshadows a lot of things, including much of the mid ’80s to early ’90s, taking a short break when Jurassic Parkwas released.

Mr. Gunpei Yokoi, or as I like to lovingly refer to him: “Papa Nintendo,” the inventor of the Game & Watch and Game Boy. Source: Meiobit

The Problem: It all started with a super bored businessman on a train

The idea for Nintendo’s first handheld came to be when Gunpei Yokoi watched a businessman on a train dink around on his calculator in a desperate attempt to stave off boredom (1). As the businessman slowly died inside, an idea came to Mr. Yokoi—what if he could create a device to help with long commutes such as this?

From this question sprung the Game & Watch beginnings, and Mr. Yokoi took his idea back to the team at Nintendo, where they started the brainstorming process. This also happens to be the beginning of what would become a strong vision for Nintendo’s handheld gaming path. The problem they chose (being boredom), their customer base (almost everyone), and the solution (eliminate boredom that can strike anytime, anyplace).

The Solution: The Game & Watch Is Born

The resulting MVP is a handheld (using a calculator chip as a processor, by the way!) (1), housing one game and a clock in the corner, hence the name “Game & Watch.” (Admittedly, for years I thought it meant “play a game and watch said game,” when it’s quite literally “a game and also there’s a watch so you can tell what time it is.”)

The first game was called “Ball”—where you played a shuffling character (named Mr. Game and Watch, as many of you may have seen in Super Smash Bros.) who is juggling some balls, trying to not drop any. In an interview with the original Game & Watch team, they discuss one of the earliest development decisions, which makes a very interesting hint if you’re looking for traces of this vision Mr. Yokoi established:

Kano: It was important throughout the entire Game & Watch series that when a player messed up, they realized the game wasn’t being unfair.

Izushi: They would think, “I’ll try again!”