“Putting into play” originates from the site Narrative Construction, and is part of a project whose goal is to offer a hands-on approach to the design of an engaging and dynamic game system from a narrative and cognitive perspective. The series illuminates how our thinking, learning, and emotions interplay when the designer proceeds from scratch to reach the desired goal of a meaningful and motivating experience.

Before initiating the hands-on process of organizing thoughts and feelings at the start of the design process, I will explain the dynamic forces behind your prime tool as a narrative constructor. The tool is more of an advantage derived from the rapid pace by how our mind is processing information that you employ in the same manner as a magician engages the receiver's perception, attention, and awareness.

Your opportunity to engage the receiver’s sense- and meaning making can be found in the drive behind our desire to understand. The dynamic forces behind this drive are so strong that we even sacrifice logic in favor to retain or retrieve the satisfying feeling of understanding. I refer to these forces as the motivating engine of learning that invites you to control the pacing of engagement through the blocking and triggering of the receivers' meaning making.

To access the motivating engine of learning and how you control the pacing of the receivers' engagement, I would like to describe the dynamic forces using a horse, and where our innate desire to understand (learn) functions as a carrot.

By presenting the carrot before the horse’s senses (touch, hearing, sight, taste, smell) you are triggering the desire to reach the carrot which motivates the horse to move towards the carrot.

To avoid making the horse lose control by not letting it get the carrot...

… you are carrying several carrots in your pocket that you arrange in a manner, so the horse’s motivation to retain or retrieve composure from the feeling of control is maintained (balanced).

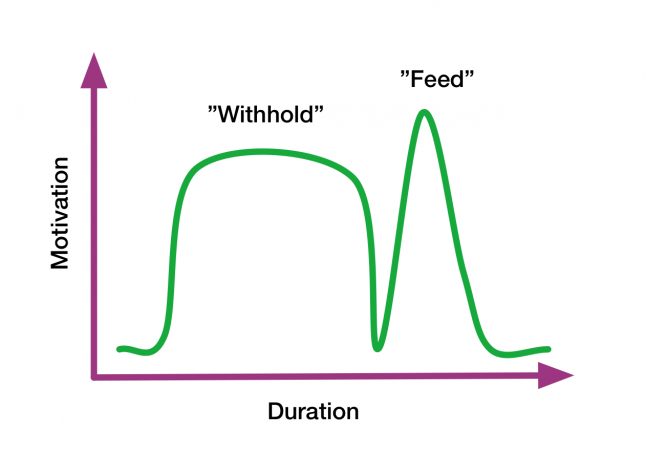

By alternating between feeding and withholding the carrots, you control the duration by tuning and balance the grades of engagement (intensity) and its effects on the emotions and motivation.

In everyday language, we call the narrative techniques employed when triggering and blocking the receiver’s meaning making surprise, suspense, and foreshadowing.

The techniques and their effects are commonly associated with theories explained by the ancestors of the media. Still, in the design of engaging and dynamic game experiences, there is much more to be explored within these narrative techniques. Above all, it is the sense of touch added to sight and hearing and the perception to “interpret” the data from the senses that requires rethinking the possibilities of the narrative as a cognitive process.

To access the unseen activities of emotions and thoughts which you are targeting when arranging (composing, tuning and balancing) the pace of your narrative with the help of a “carrot”, try replacing the “horse” with the following description of how our mind is processing information:

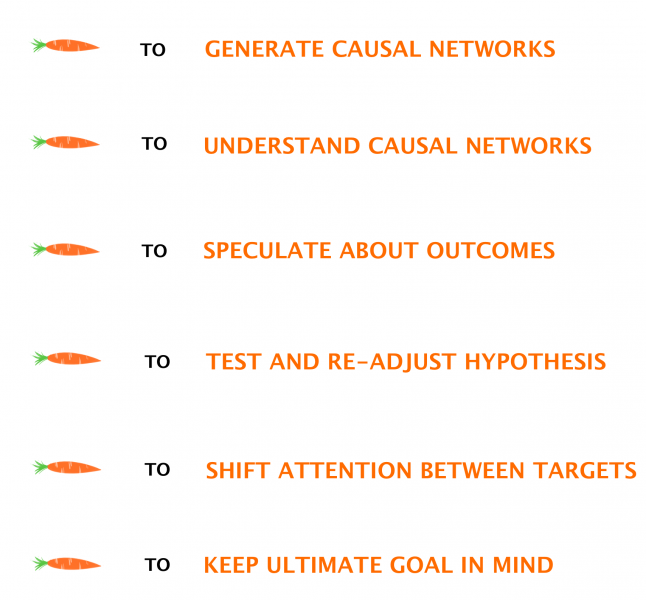

"The ability to generate inter-domain causal networks, use network understanding to speculate about potential outcomes, test and re-adjust our imaginative hypotheses, and to shift attention from one target to another, while keeping in mind the ultimate goal (e.g., subsistence) over an extended period is unique to the human mind of today."

Gärdenfors, Lombard, 2017

As explained by Gärdenfors and Lombard above, our core cognitive activities can be broken into components, thus illuminating how the “carrots” constitute the parts that will be reflected later with the help of stylistic elements of sound, graphics, effects, levels, interface, control devices, physics, systems, mechanics, etc.

You can look at each cognitive component separately to get an idea of how the parts contribute to the building of a narrative and cognitive core to a system that activates the motivating engine of learning. The diagram below illustrates how each “carrot” contributes to your intention of what you would like the receiver to do on a cognitive level.

How you can recognize the dynamic forces from the motivating engine of learning, I will give an example from the other day when I gave in to the desire to solve a crossword by using Google. If you recognize the experience of

- looking up an answer that you are supposed to figure out by yourself (as I did) or

- unlocking something in a game that (from what you know) isn’t supposed to be available

…then you have also experienced how the dynamic forces of the motivating engine of learning are translated into actions that reflect how our core cognitive activities are processing information.

Whether you are playing a game or solving a crossword puzzle, the activities generated from the forces actually invite the building of a blueprint for a dynamic space. This can be of help if you haven’t yet found a place for the stylistic elements to convey the experiences and feelings into a form.

The diagram below can be used to imagine any context where the components of the core cognitive activities are applied. It illustrates how actions are evoked, whether you are solving a crossword puzzle or feeding a gigantic ancient creature in a video game:

Back to the crossword which didn’t only engage my cognitive activities but others as well, who discussed if using Google was the right way to solve a crossword puzzle. Obviously, we have agreed on meanings that imprint our every day with rules and behaviors. These activities, in reality, share the same narrative and cognitive forces that a narrative constructor employs in the creation of an engaging and dynamic space in fiction. This is why I suggested earlier that you need to become your own narrative constructor to enhance the capacity to discern cognitive and narrative forces in reality.

Presumably, we all recognize the discussions about the “do’s and don’ts” and the expectations enforced from others and ourselves. However, the essential part of your prime tool as a narrative constructor is recognizing the narrative and cognitive forces behind the desire to understand as a possibility. For example: if a player finds an alternative way that you haven’t considered as a possibility in your design of a space. Instead of feeling that you did something wrong, give yourself a pat on the back for triggering the players’ exploratory curiosity.

The possibilities provided by the motivating engine of learning allow you to utilize the dynamic forces behind the feeling of “doing something that you aren’t supposed to do” to increase the emotional experience. For example, if you ever entered a space in a game that appeared forbidden or made you feel exclusive, as though no one else but you could have found this place, it was most likely the design of a narrative constructor who had explored the possibilities of this particular space.

Another example with less emotional impact compared to the feeling of exclusiveness is the Easter egg. Under specific circumstances, the Easter egg is an expected element, which means that if there aren't any in a particular place, a surprise is created from the fact that something expected didn’t happen. When comparing the forces behind the two effects of a surprise, you get an idea of how the emotional effects and their duration can be graded. The longer you engage the receiver's meaning making, the stronger the emotional impact of the experience, which could even linger in memory for the rest of the player’s life. The shorter the exposure, the greater the likelihood of an experience being stored at the back of our minds, making us believe it was unimportant enough to be forgotten - until the moment that we are exposed to the experience/feeling again. Depending on what you want the receiver to experience or feel, by handling the causal, spatial and temporal links you are timing the "right moment" to remind the player. If handled well, the result will be considered a spoiler if it's mentioned before others have experienced it.

How to utilize causal, spatial and temporal links to create effects by arranging the “carrots" are details that I will return to later in the series. Right now, before moving on to the hands-on part, I would like to emphasize the importance of recognizing the narrative and cognitive forces behind the prime tool in the control of motivation and pacing of engagement.

Knowing that it can feel a bit strange to see what we usually do in a millisecond depicted using the bullet-time effect, I recommend reading the previous chapter to get an insight into how our causal thinking and understanding work (see links below). As I advocate a cognitive approach to the narrative in the building of engaging and dynamic game experience, it is thanks to the game designer Fumito Ueda's transparency when sharing his thoughts on the design I have been able to introduce the 7-grades model of reasoning (Gärdenfors, Lombard, 2017).

In particular, it is the higher grades of the 7-grades model you employ as a narrative constructor to which you add the narrative keys of perspective and position. This allows you to navigate through a space to test and re-adjust the hypothesis to meet the desired goal. Regarding our desire to understand it is depicted in the 4th grade, which shows how we like to speculate about the past, present, and future by putting together pieces of what is presented before our senses. The 6th grade gives you an idea of how to move mechanics, systems, physics, effects, beliefs, feelings and desires of characters to test and re-adjust the outcome (s), which we will get to in the next section.

If you choose to read the links later, I would like to clarify that the term narrative constructor is an umbrella term I use to refer to the joint activity of giving meaning to experiences. No matter what part you are in charge of in the design process the term narrative constructor helps to focus on the narrative and cognitive activities when building an engaging and dynamic game system.

Part 1 Putting into play - A model of causal cognition on game design

Part 2, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective I

Part 3, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective II

Part 4, Putting into play - How to trigger the narrative vehicle

Part 5, Putting into play - On organizing thoughts and feelings

A short guide to the 7-grade model of reasoning

Discern the possibilities

If I were to nominate the core of cores in game development, it would be our thinking. Without it, we wouldn’t have a process, and without a process, we couldn’t build mechanics that meet the activities of our thoughts and feelings.

To create core mechanics that meet the dynamic forces of our core cognitive activities, the behavior, rules, and goal (state) of the mechanics would need to match how we test, re-adjust and shift our attention, which is pretty much what mechanics do. What to discover, though, is how our thinking and feelings from a cognitive and narrative perspective come into play when you are giving meaning to the mechanics.

Based on the simple principle that if you can discern the possibilities, you can also distinguish the constraints I will initiate the process by turning the minds-on activities into hands-on practice. This allows us to recognize what we are doing with the help of the narrative and cognition-based method: Narrative bridging.

To lower the abstraction level, I will introduce a virtual team that symbolizes our peers in the exploration of the possibilities. Please meet our co-workers whose thoughts we are going to organize in order to start the design process.