Image via Game Developer Magazine, November 2005.

This article originally appeared in the November 2005 issue of Game Developer. It was published on Gamasutra on November 16, 2015 and has been updated in 2024 to restore visuals and formatting.

While building Half-Life, which shipped in November 1998, Valve created a method of decentralized design called the Cabal Process (described in this article on Gamasutra), which used a small cabal of a few people from various disciplines to tackle the design. Needless to say, when design began on Half-Life 2, we had great interest in applying the same structure and principles to its development, too. However, the greater scope of the sequel posed some problems for the Cabal Process, so we had to tweak it until it worked for us again. This article discusses the revised Cabal Process used to make Half-Life 2.

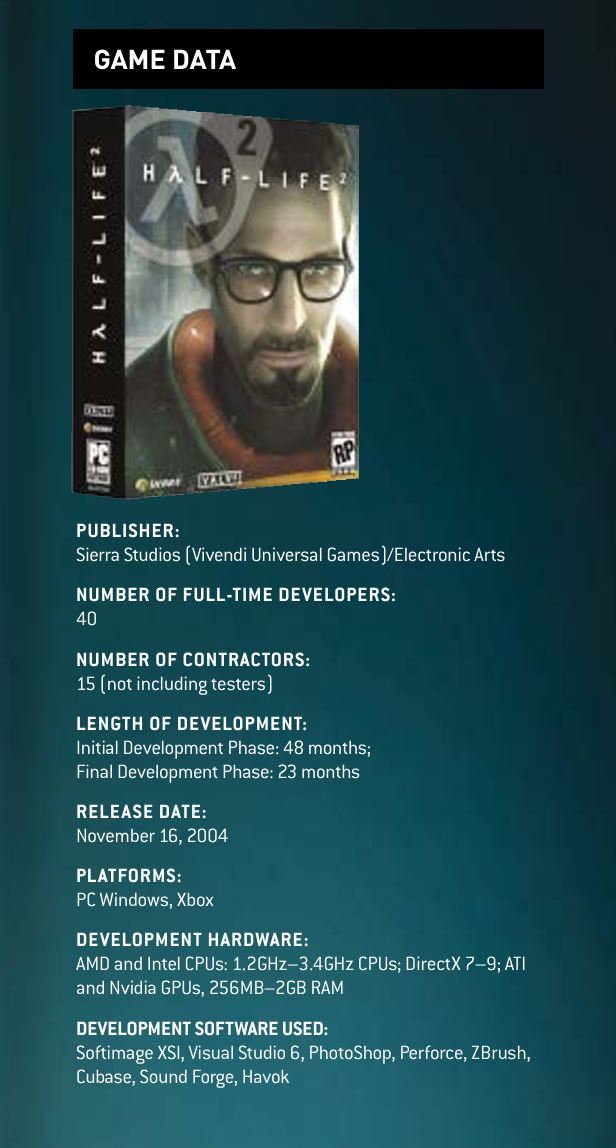

Image via Game Developer Magazine, November 2005.

Project scaling

Half-Life 2 was a project with ambitious goals. We nearly tripled the team size, and embarked on a huge technology push on all fronts. Acting, physics, AI, sound, rendering, and networking systems were all built from scratch. During the technology push, an expanded version of the original Half-Life cabal met for months, attempting to create a complete design document similar to the first one. Design work during the early phase of development progressed very slowly because we found it difficult to predict what kinds of designs our technology would enable once it was finished. To make matters worse, the resulting design relied on many game elements that were purely theoretical.

By the time the Source technology had matured, we found ourselves in a position similar, in some ways, to where we were at the start of the Cabal Process for Half-Life, but very different in others. In terms of design, we were better off. We had a full story timeline, detailed story snippets, all the major character profiles, a set of locations and drawings, and a fairly clear idea of what technology we would have for the final game. In terms of production, though, we only had a bunch of raw material in the bank: some weapons, some cool monsters (and some not-so-cool monsters), and pieces of interesting levels. However, as with Half-Life, at this stage of development, the technology was not being taken advantage of. You couldn’t play the game all the way through, and none of the levels were tied together in a coherent fashion.

Once we knew what our engine could do and had enough raw material in the bank to use as constraints to drive the design, the Cabal Process began to work as efficiently for us as it had during the development of Half-Life.

The problem now was, given the much larger scale of the game and larger number of people working on the project, the Cabal Process itself became a bottleneck. It couldn’t produce content fast enough. As a result, we created three nearly independent design cabals, each responsible for designing and producing roughly one-third of the game, plus dedicated cabals for art, sound, and acting.

Although the concept was born years earlier, the APC was not introduced into the game until the last four months of the project. Image and caption via Game Developer Magazine, November 2005.

Back in the saddle again

Each cabal consisted of four or five people, half level designers and half programmers. While developing Half-Life, we decided that this was the ideal size. Larger cabals resulted in diluted design meetings and smaller ones risked a dearth of ideas. We included both programmers and level designers because most design iteration occurred through changes to AI, game code, or levels. Each cabal also included one engine programmer who would develop new technology required by the designs. For productivity reasons, we wanted each team member to have a “demanding customer” on the same cabal, someone who consumed that person’s work. Level designers were customers of programmers in that they used the gameplay elements and AI created by the programmers. Programmers were customers of level designers in that they needed levels as a venue to refine their code. The members of each cabal shared an office to reduce communications overhead and, as we discovered, improve prioritization. People were far less likely to get sidetracked by non-critical tasks if their teammates sat nearby to serve as instant triage.

The Half-Life cabal included artists and a writer, whereas Half-Life 2’s multi-cabal structure prompted us to treat artists and writers as shared resources. We created an art team, an acting team, and a sound team (actually just a single sound designer). The art team collaborated with the design cabals on the look of the environments, monsters, and characters in the early stages of development and made the levels look great once the gameplay in those levels was stable. The sound team worked with the design cabals to produce stand-in sounds during gameplay prototyping and to create a final sound treatment of the levels after the design stabilized. The acting team collaborated with the design cabals to seed levels with mission goals and story rewards, and they produced any animations the levels required. The acting team also served as an independent fourth design cabal for the story-heavy sections of the game, such as Kleiner’s Lab, Black Mesa East, and Breen’s chamber.

Despite the large structural changes to the Cabal Process, there still were many aspects of the original process (as described in our previous article) that remained intact. The way each cabal generated designs remained largely unchanged. We preserved our edict, “He who designs it, builds it,” in the belief that the best designs are influenced by the realities of production. People who are very cognizant of all the tradeoffs inherent to a given implementation are going to make better design choices. We continued to discourage a sense of sole ownership because we believe that having more hands on a given section of the game ultimately produces higher quality. Our playtesting techniques remained the same, and we continued to use them as a way to settle design arguments. As with Half-Life, the cabals were completely responsible for meeting the quality standards in the levels they owned.

The result was that we had six teams, all of whose work—models, materials, sound, animation, lighting, story, and game design— had to come together in the levels themselves. Clearly, managing this process was going to be tricky but essential for us to succeed.

There were some obvious problems, of course. How would we manage and reduce the cost of the many interdependencies between our six teams? How would we allow every team to apply important constraints to the design? How would we create a consistent design and level of quality in the face of three independent design teams? These problems were eventually solved on a case-by-case basis.

Valve used over three hours of recorded dialogue to bring the HALF-LIFE 2characters to life, compiled from multiple recording sessions with each voice actor. Image and caption via Game Developer Magazine, November 2005.

Keyframing pose

Half-Life 2 contains more than three hours of acting, and recording the dialogue for these scenes wasn’t always easy. In some cases, it required flying to Los Angeles, exploiting a limited window in an actor’s busy schedule, and using a fixed number of studio sessions, after which we would be on our own. In an ideal world, we would have gone through a more traditional screenwriting process, but that would only have been possible if we knew in advance where our game design process was going to take us. We couldn’t leave all the acting until the end because then there wouldn’t be enough time to improve it; so story and gameplay had to develop concurrently.

At first, the two seemed inextricably linked, which presented an interesting challenge: How would we give the gameplay cabals, whose process (and result) was fluid and unpredictable, the freedom to experiment while presenting a stable enough framework on which we could hang a story? We eventually settled into a process whereby story provided keyframes that served to constrain the game design. For example, in designing the Route Kanal and Water Hazard chapters, we knew the player would start on the run from City 17 forces outside Kleiner’s Lab and finish at Black Mesa East, far from City 17. The story elements that fell between those two story keyframes were purposely left vague until later in the process when the gameplay had solidified. As long as the gameplay cabal satisfied the constraints of the story keyframes, the cabal was free to take the gameplay in whatever direction seemed most promising without fear of leaving the story in an untenable position.

The helicopter battle at the end of the Canals sequence was a keyframe moment used to constrain the design of the Canals. Caption and image via Game Developer Magazine, November 2005.

Once a chapter’s gameplay was finalized, the responsible gameplay cabal and the acting cabal met to draw up a list of places within the chapter where story elements could be added. Some were required by the gameplay, such as the delivery of short-term mission goals or the explanation of a game mechanic. Others were important for the story or for player motivation, such as the reinforcement of a larger overarching goal (like reminding the player that they had to get to Eli’s during Route Kanal). Finally, some were story-based rewards that served to enrich the player experience. Even with this process, the story still had to be supple enough to respond to unexpected gameplay demands, such as when Ravenholm moved from before Black Mesa East to after, once the potential of the gravity gun to enhance Ravenholm was realized.

Alyx’s original companion was a ferret-like alien. Somehow Dog seemed like a better friend. Image and caption via Game Developer Magazine, November 2005.

Insider art

The art burden of Half-Life 2 was an order of magnitude greater than that of Half-Life. Half-Life 2 used more than 3,500 models, nearly 10,000 materials, and individual maps as big as 20MB (compared to Half-Life’s 300 models, 4,000 materials, and 3MB map files)—a tremendous investment in visual quality. In order to produce this many art assets with a relatively small team of artists, we had to optimize the art production pipeline and insulate it from gameplay changes as much as possible.

The art production for a chapter began with the creation of concept sketches, which were developed early in the cabal’s design process once the general setting was established. In many cases, the concepts were developed even earlier based on the broad story design, in which case they served to inspire the game design. Once the concepts and gameplay were deemed compatible, the concepts were developed into style guides—maps devoid of gameplay that would serve as a template for building final production maps. The style guides both influenced and were influenced by gameplay prototypes that were developed simultaneously. For example, the buggy’s handling characteristics influenced the scale of the coastal landscapes in which it was used and vice-versa.

Top: Orange maps of the Prison area, used for gameplay prototyping. Bottom: The final Prison map, after input from the orange map tests. Images and captions via Game Developer Magazine, November 2005.

Agent Orange

Initial gameplay prototyping for each chapter took place on orange maps. Orange maps use an orange grid texture for walls and a gray one for floors and ceilings, and using them solved a number of issues we ran into early on.

First, it prevented level designers from investing in the art for an area before the core game mechanics had been validated through playtesting. Effecting this practice dramatically reduced the iteration cost and avoided any early commitment to the look of an area. It also solved the problem of prematurely critiquing art when team members were supposed to be critiquing a gameplay prototype. Finally, it allowed the art team more freedom to experiment with visual themes, since they could do so independent of the gameplay prototypes.

Successful gameplay prototypes and style guides were used as the basis for building the final levels. Once those playtested successfully, they were handed off to the art team for an art pass. During the art pass, all level designer-created stand-in geometry was replaced by final models. Final materials were applied to the level, lighting was adjusted or recreated from scratch, and auxiliary elements, such as fire, fog, and skyboxes, were added.

Through this process, the playable level was made to more closely match the vision of the original concept art without breaking the gameplay. In practice, though, gameplay did sometimes break in unexpected ways, such as when playtesters refused to walk on a large suspension bridge once a realistically thin-framed model replaced the chunkier, level designer-created predecessor. Because of this inherent dependency between visual design and the communication of game mechanics, the design cabals always held playtests after the art pass to verify that gameplay still worked.

Right: This illustration of Gordon Freeman was created by a member of the HALF-LIFE community. Images and caption via Game Developer Magazine, November 2005.

Symbolic links

To allow multiple teams to work simultaneously on a single level without causing stalls, we tried as much as possible to structure our tools around independent files that were connected by a system of symbolic links. Symbolic links are human readable references, resolved at runtime, that both code and content use to refer to another code or content resource. For example, we replaced direct references to raw sound files in our maps with names of entries in a sound script file instead. Each entry in the script file specified such variables as pitch, volume, and random file selection for the sound. This allowed our sound designer to replace or modify sounds without affecting level designers. Before we had symbolic links, level designers had to hand off maps to the sound designer and not work on them until the sounds were finished. Also, by using level-specific sound names for level-specific sounds, the sound designer could change sounds without disturbing other maps.

No tags.