It’s been over two years since The Painscreek Killings (TPK) launched on September 27, 2017. Prior to that, it took a little over five years to develop. Looking back, TPK struggled in development and failed in marketing, but sold about 40,000 units as of today and somehow was able to keep us afloat as a startup company. Was it all worth it? We would say yes. But that’s not what this article is only about.

What we hope through this postmortem is that we could share our experience from start to finish with those who are in the same boat as us - indie developers creating mystery investigation games using the walking simulator formula - to take what worked for us and hopefully avoid the pitfalls that we faced.

First, about detective games…

Detective games don't sell. At least that's what we come to realize after releasing TPK and looking at most indie games in the detective genre. Either nobody wants to play them or we failed to create good ones. Unfortunately (or fortunately), we didn't know that. Thus, TPK was born.

As a quick introduction, TPK is a 3D first-person view, mystery investigation where the player plays a journalist investigator in an abandoned town trying to find a story before it gets auctioned off and bulldozed. What starts out as a leisurely search turns into a full-blown cold case investigation.

The concept

A person was killed. Another person is the killer. Your job is to find out who the killer is. Anyone who have seen the anime ‘Detective Conan’ will know right away what it’s about: there is only one truth and it’s about finding it out. We played quite a number of detective investigation games and while they work, none made us feel like a true detective. Either the game handholds us too much, or the game is too linear, or they are impossible to solve without guides. We decided to make an investigation game that we want to play, one that makes us feel like a detective. Since it’s our first time into game development and we did not have a programmer, we decided to keep it simple: it will be a walking simulator, there will be no in-game character models to make, the programming should be kept to a minimum and done through visual scripting, etc. To counter all that limitations, the game had to be immersive. To achieve that, we did the following.

("The truth shall set you free.")

When watching any detective film, all the audience want is to know who the killer is. If we could keep players guessing who the killer is until the end of the game, it could just work. That was one of the core design we embraced right from the start.

Players should be able to decide how they would start their investigation. We did not want a linear game where players are told to progress from point A to point B. To achieve that, we went for an open-world, free roaming experience. Since the goals are player-created and not dictated by the game, it would enhance the overall detective experience.

We also wanted to encourage players to really look around and search for important clues and items rather than having the items highlighted or outlined. In order not to make it too difficult for players, everything was placed in a believable manner, every puzzle was provided with at least one or more clues, and some puzzles can be solved without finding the hint but through logical thinking. An example in TPK was the slim jim. If you grew up in the 90s, you would probably know that it's a tool used by thieves to unlock car doors. Players might also come across an item that do not make sense at the time they found it, but would make perfect sense later on. One such example was the shovel, which was found in Oliver's Photography store but used in the cemetery.

When it comes to the puzzles, they have to be logical and make sense, just like in the real world. We didn't want to pull a lever in room A that unlocked a hidden doorway in room B without being informed. If players have to access twelve locations sprawled across a town, then the clues and hints need to be logical for them to proceed. The game can be hard or challenging, but it should not be illogical.

We also wanted the game to make players find the right clues to proceed. Rather than knocking on every door found in the game, players need to find clues that would lead their investigation in the right direction. Many recent games have players clear one stage before continuing on to the next, knowing that they could not proceed further if they did not clear that particular stage. TPK, on the other hand, introduced the whole town right from the start. Because of that, it’s futile to knock on every door and see which doors can be opened. Instead, what was the first thing that caught their attention while investigating the Sheriff’s outpost? Was it the mansion where Vivian’s body was found? How about the Church where Scott, the suspect, used to work? It’s these kind of clues, whether direct or indirect, that should give the players a nod towards the direction in which to proceed with their investigations.

(Can you unlock the locked stairway that leads to the secret basement?)

(Can you unlock the locked stairway that leads to the secret basement?)

The game had to be in 3d to achieve the level of immersion, which was difficult to achieve in 2d. We also decided to abandon any quest markers, game hints, overhead compass, etc. In short, we decided to make an experience that resembles real life. Anything that does not appear in real life should not be in the game.

One other important factor was getting the atmosphere right. Why do most horror or scary games happen at night? Could a game take place in broad daylight and still make you feel afraid or uneasy? We looked at games, films and TV shows while researching on this topic. There's a movie called The Ring. The American version had a lot of night/dark scenes while the Japanese version had more daytime scenes. The American version had jump scares while the Japanese version didn't employ that technique. When Sadako came out of the television, the American version was scary for that moment, but that moment only. The Japanese version, on the other hand, had me scared for days. So how did the Japanese film have such a stronger impact than the American version? We realize you don't really need jump scares to make a film or game scary. Jump scares are like fluffs with no substance - the impact is there when it happened, but diminishes quickly when it's over. Movies like Sixth Sense and Zodiac created tension and fear in a way that made their audiences remember them long after the movie is over. We wanted to achieve that effect so we focused on building up the tension through music, atmosphere, and most importantly, story hooks. It’s for this reason we decided that TPK will happen during the day.

(The view from the bench behind the mansion shows how TPK tried to incorporate the bleak mysterious atmosphere even though it's in broad daylight.)

(The view from the bench behind the mansion shows how TPK tried to incorporate the bleak mysterious atmosphere even though it's in broad daylight.)

The execution

Before developing the game, we tested the Unreal Development Kit (UDK) and the Unity 4 game engine. Although UDK seemed more powerful at that time, we decided to go with Unity for the following reason: we wanted to know everything under the hood. UDK seemed to have everything right from the get go while Unity forces us to create everything from scratch. Although development will seem longer with Unity, it will make us understand the engine better. In addition, UDK had a 25% royalty fee while Unity was free. So we went with Unity.

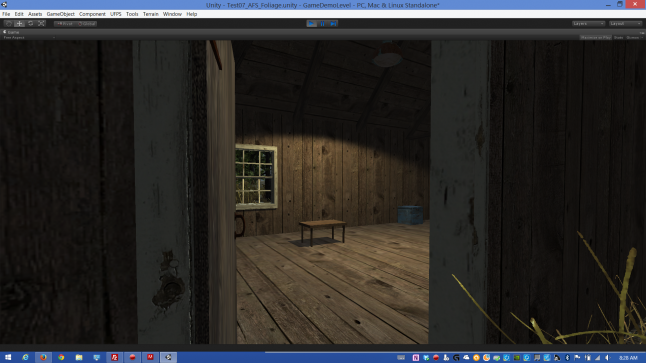

(Early Unity 4 game engine test.)

(Early Unity 4 game engine test.)

We set out to make a detective game right from the start. Instead of coming up with a story first, we structured a mold for it. What would it take to make a detective game that we would want to play? We decided on the following design focuses: (1) it has to hook the players, (2) it has to mimic a real detective experience, and (3) it has to make the players feel smart.

To hook the players, we focused on both story and characters arcs. We layered our story like an onion for players to peel, revealing bits and pieces of information crucial to unraveling the whole storyline. We also structured the story into 3 acts, with 2 plot-points and a mid-point inserted in between the acts to hook the players and remind them of the goal. As for characters, we decided early on that all the important NPCs will have their own character arcs so how they were portrayed at the start and who they really were by the end will be quite different.

To mimic a real detective experience, we thought of how would a police solve a case. What we realized was that progression is determined by clues and leads, being perceptive is necessary and that it wouldn’t be easy at all. Our house/workplace was burglarized twice, with the second one involving numerous police officers and a forensic guy who combed through the place picking up bloodstained samples left by the intruders. Three years later, the case is yet to be solved. Thus, we decided on the following: no handholding, logical puzzles that are solved through hints and clues, and a free-roaming open world game.

To make the players feel smart, we decided on the following: provide multiple but subtle hints for every main ‘puzzle’, a breadcrumb system as opposed to trying to make a Sherlock Holmes out of the player, and let players connect the dots themselves to create their personal ‘Ah-ha!’ moments.

Along the way, we also solidified our design philosophy: (1) focus on our strengths, (2) go from general to details, and (3) story is the priority and if we have to compromise, compromise the graphics. That became the foundation for the next five-and-a-half years of developing our game.

We knew the importance of 3-act story structure and how crucial it was to making a film work, but will it work for a game? Googling this topic yields many thumbed down responses and articles. Yet we still went with it because of the influence from films. We needed to have plot-points throughout in order to hook the players and some form of structure for the story to build up from start to finish. Using the 3-act structure also allowed us to re-affirm that the story‘s design was leading somewhere and not just going anywhere. We were able to envision how players might experience the game the way it’s intended to be. It’s not perfect because it limited the free-roaming aspect to a certain degree, but was a necessary compromise for a game like ours.

Once the story’s structure had been laid out, we moved to design sheets. We decided that the era would be around the late 1990s. There were several reasons for that. First, we were familiar with the 80s and 90s, so it was a no-brainer to go with that era. Second, we could research everything on Google without coming up with new designs. Third, we could implement stories and journals based on our childhood years, which helped to cement the story’s believability and add a certain level of realism to the NPCs’ storylines.

(Early village design that would eventually be scrapped for a better layout.)

(Early village design that would eventually be scrapped for a better layout.)

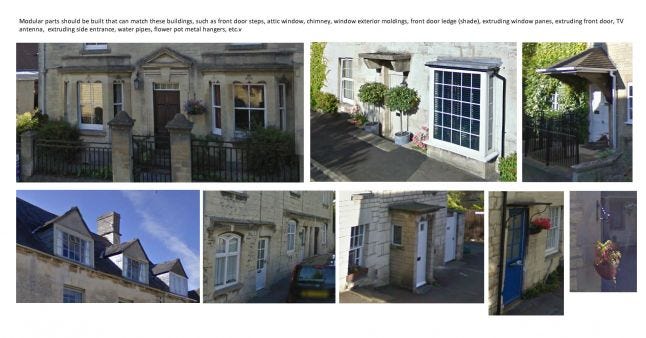

(Research done to break up different parts of a building in order to make them modular.)

(Research done to break up different parts of a building in order to make them modular.)

After the story was done and while the design sheets were still being worked on, the 3D asset creation phase started. That time, a volunteer who came to learn about game development helped us with asset creation. His arrival helped to free my partner to learn programming, something we didn’t know would be crucial in helping TPK come to fruition. We knew all games need programmers to make, but we thought that with the help of Unity’s asset store, we would not require a programmer to pull the game off, especially when it’s a walking simulator game. We were wrong. Having a programmer was indispensable.

The task of a programmer seemed simple at first due to the nature of our game. As time went on, however, the task list grew and the difficulty challenge rose. Over time, our programmer's skill improved and she was able to pull off most of them. Later, she even replaced plugins bought from the Unity asset store with her own custom made scripts. This was one big step for us because towards the end of development, we implemented some crucial game mechanics, one of them being the in-game journal.

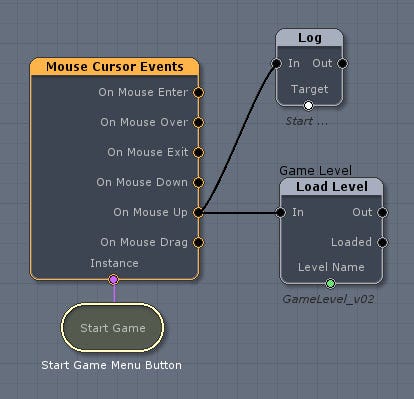

(Testing uScript at an early stage of development.)

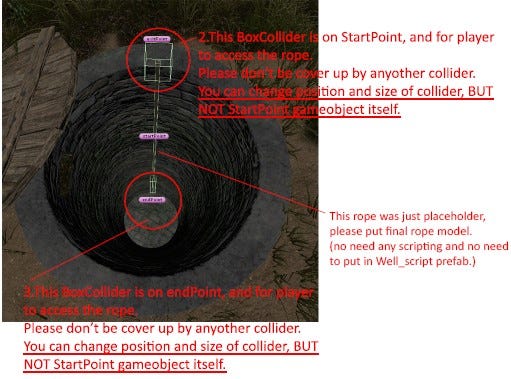

(Notes provided by the programmer on how to use her custom made script.)

A year later, three high school graduates joined our team. Two of them helped with environment/prop asset creation while the third became our level designer. Similar to the first volunteer, the three of them were learning the ropes on game development while helping out at the same time. We also had someone helping out with the design sheets. Now our development team consisted of seven people: one game designer/writer, one programmer, one on design she