Price, funding, revenue, development costs... these are not terms traditionally associated with roguelikes. The situation has changed significantly over the past several years, though. Not only are there many more roguelikes these days, but some of them (*gasp*) even cost real money!

Having made the leap from years of hobbydev to years of commercial roguelikedev, I have some thoughts and experiences to share on the somewhat contentious idea of raising money for a roguelike, and pricing strategies in general. Although I write in terms of roguelikes, most of the same principles can be applied to other genres as well.

In short, Cogmind's approach to pricing has worked out perfectly, initially meeting my expectations, and then before long exceeded them. Repeatedly.

Why Pay for a Roguelike?

Before I get into examples, the short answer is that money makes more things possible. Who doesn't want even more higher quality games from their favorite genre?

As for specifically what money can do for roguelikes, not too long ago on the Cataclysm: Dark Days Ahead forum a relevant thread popped up.

C:DDA Forums: "What needs to be done to compete with Cogmind's UI?"

Excerpts from a discussion on C:DDA UI development.

You see this a lot in roguelike development, where accessibility and UI features are an afterthought. That's not to say they aren't important, nor would many developers make such a claim, but it is widely considered a less enjoyable part of creating a roguelike. Roguelikes are all about adding new mechanics and content--heck, rapid feature development is one of ASCII's strong suits to begin with! UI work requires yet more time (on top of all the other things RL dev entails) in a very different area of expertise.

Kevin (C:DDA developer) at the end there makes the point well: Hobby projects are more about what the dev wants to do. I can say from experience that after having switched from hobby to commercial development, the focus shifts towards a lot of what the dev should/must do. Sure there's still the fun stuff--the new mechanics, new map generators, finding new and exciting ways to killchallenge players... but I also spend plenty of time doing things I don't necessarily feel like doing.

You know, like most any other job that pays :P

A developer charging money for a game has an obligation to serve the player wherever possible, and that means devoting proper attention and resources to usability. Note that this in no way implies sacrificing creative control, it just means treating the project as a proper business--taking feedback, interacting with players (who double as customers), and providing customer service. As such, accessibility features have a much higher priority for me, which a lot of players appreciate.

Players get so much more than that, though. Increased production value and quality make up the bulk of obvious benefits from paid roguelikes. Being able to invest extra time or money means:

Extensive professional tilesets of a consistent quality and style. ADOM currently has over 6,000 tiles; ToME4 has a mind-boggling total north of 20,000; Caves of Qud has upwards of 5,000; Cogmind has 1,165 (plus over a hundred custom font bitmaps, a thousand pieces of ASCII art, and many hundreds of procedural animations). And because they're all in development, these totals are still increasing as time goes by! (It's early yet for DoomRL successor Jupiter Hell, but with all those 3D assets it's in a league of its own and certainly not happening without funding! (already acquired through KS))

Sound effects aren't something that a lot of roguelikes do--that's mostly roguelite territory, but Cogmind has made it a big part of the experience with over a thousand samples and counting (far more than any other roguelike and most other indie games).

Music. Some roguelikes do this, too! (Still to write: my own article on that topic.)

Certainly plenty of perfectly good roguelikes have none of these things, but many of the more widely popular ones do, not to mention the potentially long stretches with no fixes for bugs reported in non-commercial roguelikes.

Optional elements aside, considering the time-intensive nature of roguelike development, simply having more time to dedicate to new features is a big thing. A revenue stream enables continuous development, much more desirable than the sporadic updates endemic to hobbyist gamedev (for which the ARRP was a somewhat successful attempt to remedy, but still can't compare to directly funding the process!).

Development on Ultima Ratio Regum, an amazing free roguelike project started in 2011 but only about half done by now, was unexpectedly halted for some months shortly before a planned release last year. Mark is now back at it again, but a number of other roguelikes have died or faded out over the years before reaching completion. Pure hobby projects tend to progress more slowly, and therefore stand a greater and greater chance of dying as time goes on. It's just a fact of life, in which any number of causes can spell the end of (or at least interrupt) development, be it family, studies, work, a change of interests, or "a bigger better idea!!1" :). From that perspective, means to accelerate progress are a good thing (and of course for their part players won't complain about access to more timely updates!).

Honestly it's a huge amount of pressure to keep up that near-nonstop progress, but the ability to (relatively speaking) quickly and efficiently put together a world that others can enjoy is worth it.

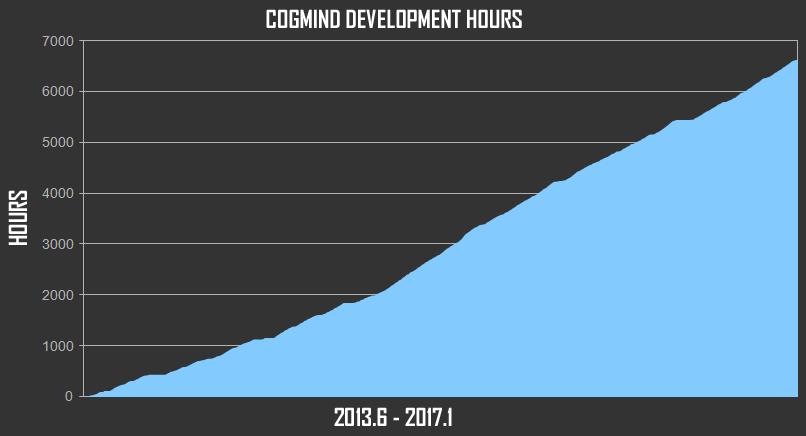

Cogmind Cumulative Development Hours, 2013.6-2017.1

Cogmind cumulative development hours, 2013.6-2017.1.As an experiment, let's look at the hours I've put into Cogmind as of this writing (6,623) in a different light: What if this were a hobby project done in my spare time? Excluding basic needs and all other responsibilities, based on years of data I generally have about 50 hours to spare each week for work (all of which currently goes towards Cogmind). Assuming I use up 40 of that for a different job and develop purely as a hobby instead, and also making the big assumption that doing this other job wouldn't leave me even more exhausted and desiring extra time to relax and get away from brain-draining activities (it would), that leaves 10 hours per week... 6,623 h / 10 h/wk = 662.3 weeks, or 12.7 years!

So rather than Cogmind being what it is today in January 2017, having started as a hobby back at the original date of June 2013 it would not reach its current state until July 2025. Sure we could chop off a year or two because, yes, I might spend vacation time working as well (though we'd also have to cut out the occasional weeks where I'd be too busy with other life stuff)--anyway, it's a generalization, but no matter how you look at it that's still terribly slow.

Then of course there's the fact that it's not done yet :P. I can say for sure that including post-1.0 work it'll easily top 8,000 hours (beyond that I don't really know).

In the end, most roguelikes and features are technically possible without any funding whatsoever, but it's going to take a lot longer (which, again, increases the chance of failure), or a lot of manpower (DCSS is a good, if rare, example there).

Why $30? Balancing Price with Other Factors

Although as I write this alpha access is available for $25, in 2015 Cogmind was introduced at $30, the price at which it remained for the entire first year of public alpha. As you would expect, reactions to this number ran the entire spectrum from "for an alpha?!?!?" to "totally happy to pay that!"

I based the specific number on a couple data points, first and foremost what I'd noticed from video game Kickstarter campaigns, that early access as a "perk" often came with tiers upwards of $30. Even outside KS, I found games like RimWorld, similarly a highly-replayable game under long-term alpha development at a good pace by a very active dev, which priced its alpha access at $30.

Overall it felt like a plausible range was somewhere around $20-$30. I would definitely not claim this approach is good for maximizing revenue potential, or even maximizing players while still bringing in "sufficient" revenue, but that wasn't the goal!

Elastic Demand Graph

Graph demonstrating the concept of elastic demand (source). Video game demand is pretty darned elastic!

It's fairly obvious that a lower price point might very well outsell the current sales model in terms of total revenue, but to me there are more important factors than money to consider in the short term. The point of alpha funding is to keep development humming along until 1.0, before which too many players actually becomes a problem!

While not necessarily true of all devs, I believe in the importance of being active in the community, responding to everyone with a concern, question, or some other need of support, while also putting effort into making resources, extensive progress updates, and other information available outside the game. This requires a significant time investment, the effects of which are even more pronounced as a lone developer where talking to players means I'm not making real progress on the game itself.

Lower prices naturally attract more players, which given this community-oriented model will inevitably slow development as more and more time is spent on community management. But I love having the opportunity to maintain closer relations with a smaller player base, even adding custom options at the request of a single player, while still having plenty of time to work on the next release. So in this regard a higher price is beneficial for both development and the ongoing alpha player experience.

Game development is also incredibly risky, so it's nice to use any knowns to mitigate elements of risk wherever possible. This, too, played a role in the original pricing decisions, which you can see below from my general thought process:

I do know that I have an established fan base who would be willing to pay more for a quality roguelike with quality continuous development and support.

I don't know whether lowering the price to something more common across the entire indie market (like <=$10) would be able to attract enough players to even make up the difference. But I do know that even if it could, having 2-3 times as many players would be a larger burden on the process and unnecessarily slow development. The resulting "high noise-to-signal ratio" also makes it harder to focus on the best design decisions.

Niche games, especially those with something truly unique to offer, can afford to charge more, and in many cases must charge more in order to be at all sustainable. Long-term sustainability is quite important to me, since this isn't a one-off thing and I hope to not only develop it further beyond 1.0, but also work on other games as well. It's (hopefully) a permanent job.

In that light, a $30 price point seemed the much safer route.

From a purely economic standpoint, where time is not a limiting factor (i.e. development and support can and will continue for quite a while), setting a higher price is also just smart business. Eldiran over on /r/gamedev (where especially when starting out I read a lot of first-hand industry info that was very helpful) put it very well in response to a question about how discounts damage indie sales: