“Putting into play” originates from the site Narrative Construction, whose goal is to offer a hands-on approach to the design of an engaging and dynamic game system from a narrative and cognitive perspective. The series illuminates how our thinking, learning, and emotions interplay when the designer proceeds from scratch to reach the desired goal of a meaningful and motivating experience.

Before shifting to interactive media, I wrote story arcs for films and television series. The technique of scriptwriting was to follow your gut, establish a conflict, take it to a climax, and end it with a twist. The receiver's engagement was built into the dramatic story structure, which meant that focus was laid on the character's motivations, relations, and behavior. As long as the audience stayed seated and the ratings were good, work continued as usual.

Since my gut was what motivated me to realize new experiences and feelings through a tool, I didn't look at the change of media as anything other than a natural act of using a new tool. However, when asked to write a canonic story for a game plot like a film, I felt my gut protesting.

Why change tools if it wouldn’t give me a chance to explore new possibilities?

The problem with the gut is that it doesn't come with an answer. It can just leave you there with an awkward feeling that things don’t make sense. The good thing about the gut is that it's loyal as hell. It can just turn itself into a mood and linger in your memory as a reminder until your brain works out the answer. The effectiveness of your gut can be improved if you get into the practice of backing it up with a drive state of curiosity, which helps to make sure you don’t miss anything that can be useful to the creative process (see Part 6, Putting into play).

Over the years of game development, it has been tangible to those working with narratives that something doesn’t make sense by how the narrative is conceived as a canonic story from other media. For example, you would never hear someone asking you to construct your story like a video game because video games are considered to be what stories aren't - interactive. And if you get to work with game productions as a writer or narrative designer, it is not given you will be able to work with the development of the parts that are considered to be gameplay related, such as the mechanics and systems.

The game and a narrative designer Chris Bateman says in an article about the understanding of the narrative craft in the game industry:

"Narrative design is "one of the toughest crafts in the whole of video games -- made even tougher by the fact that most developers don't even think that it's part of their process."

How come the narrative isn't a part of the process yet? Haven't we got over the linearity versus the interactivity debates? Or has arguing about story versus game exhausted us enough to accept it as a fact?

But what if the narrative is more than the parts, the story, and the medium?

Fitting the narrative within games

Since the narrative is fundamental to the cognitive process, being intrinsically connected to our learning and understanding, which permeate the entire process by how you are giving meaning to the parts that are to be presented before the receiver's senses. Today, it would seem that the game industry has created its own narrative about the narrative.

Ever since the game industry built up speed to its production of story-driven games, intense work has been in progress to make the narrative fit within games. We have now become so used to the narrative being adapted to games that the craft of adaptation has earned its own terms: firstly, converting, which means redesigning the existing storyline of a film or book to fit a video game. One example is the James Cameron moving picture Avatar currently being converted into a game. Secondly, the term merging refers to the craft of making a dramatic story structure fit with the gameplay.

The craft of fitting the story to games has even earned its own genre - the so-called narrative- or story-driven games. The genre is so established that if you claim there are other ways to understand the narrative, people tend to say “I like stories in video games”, as though you were about to remove the fish from the chips.

Since the narrative has turned into something you like or not, it has also become an element you choose to have in your game or not. Associating the narrative with large-scale AAA productions, making a narrative-driven game is even considered an economic risk. This conception of the narrative also rubs off on writers and narrative designers as being something you may either need or not as opposed to programmers, graphic artists, level- and game designers who are necessary.

By looking at the narrative as being a choice, it isn't strange that the narrative is sometimes considered as being a part of the process and sometimes not.

Bateman suggests that instead of thinking of the story as "the other side of the coin in games," one should "think of story as one more game system.". To bridge the gap he proposes an exchange of techniques and experience between conventional writing and game design.

Since I am at the final sprint of Putting into play, which treats the narrative construction of meaning and how emotions assist the design of an engaging and dynamic game system, I intend to take Bateman's call and add my part to uniting the systems (and minds). As I have one foot in conventional writing, and the other on in game design, I will take you on a trip to find the hidden art of pacing, which means we will trace back to where the core of engagement and motivation resides.

As in previous sections, I will provide a cognitive and narrative approach to the design of an engaging and dynamic game system from a hands-on perspective on the organization, arrangement, and direction of the thoughts and feelings towards the goal of what the receiver should experience or feel.

Tracing the hidden pacing of engagement

The first time I came in contact with pacing was at a meeting to discuss a playwright at the dramatic department of Stockholm City Theater. Instead of speaking in standard terms about scenes and characters, they turned the playwright into a music piece. The characters' interactions by how they talked, moved, and behaved were translated into terms of volume and tempo. Using rhythm, they defined the timing of when elements occurred and how long they lasted, and how far from each other they were as to appear again.

First, I was confused and wondered when they should get to the point. Afterward, I was amazed by how it made perfect sense of how words and music/sound connected.

It was not until I started working with game design that I got the opportunity to experience the art of pacing as a feeling of rhythm again. Then it was from the perspective of how you provide and withhold meanings to engage and motivate the receiver's thinking. It was also then the gap between conventional writing, and game design became visible by how the story structure worked as a method to access the pacing of actions from the receiver's perspective.

By breaking down the story structure and pacing out the content across sequences so as to meet the receiver's building of experiences and engagement, you combine the contrasts of tempo (fast/slow) and intensity (strong/soft). In relation to actions, intense combats are followed by peaceful puzzles or an exploration of the world while gathering objects. It was also here, in the craft of pacing out the content through missions, levels, environments, and worlds, you could find the systems of quests, dialogue-trees branched storylines and cinematic that writers and narrative designers are usually in charge of.

Since pacing is at the heart of conventional writing and game design, which rhythm and tempo accommodate the core to the engaging and motivating forces, I will start by bringing on the dramatic story structure to see where the core resides that connect structures and crafts.

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Since the whole idea with the art of pacing is to trigger the engaging and motivating forces, which "tricks" by how you entice curiosity shouldn't be noticed by the receiver. The problem, though, is if the core to the pacing is hidden to the constructor.

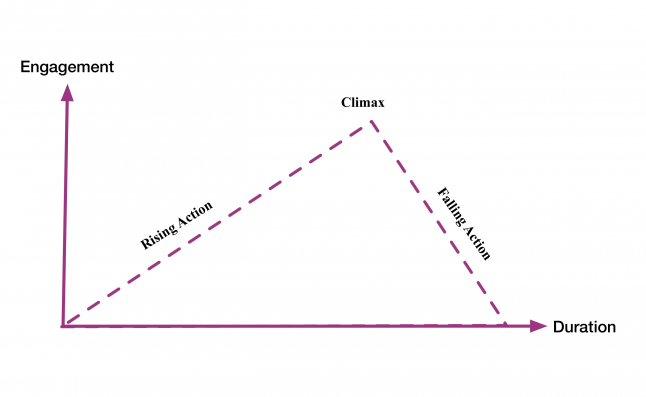

The dramatic story structure (also known as the three-act structure) is very good at appearing as if it shows where the hidden engine to the pacing resides by how the acts, turning-points, and conflicts capture an overarching rhythm. At first sight, the structure seems to correspond very well to the idea of how the feeling of being aroused goes up and then down. The structure also hints at converting the rising and falling actions into components that could fit the interactivity of a game.

But as the story structure leads to focus on the development of the characters' motivations, relations, and behaviors while a gameplay's structuring concentrates on the receiver's actions. When taking a closer look at the dramatic story structure as to ask whose actions are actually rising and falling, the structure veils some essential parts that concern the engaging and motivating forces to be from the receiver's perspective and position. These forces contain the receiver's feelings, experiences, and expectations brought by the overall rhythm, which captures the core of a mood that follows the receiver after the movie or game ends. This core of the mood works as a drive, which desires encourage us to relive the experience and feelings, which can be noticed when we express appreciation to a specific genre or style (but it can also generate the opposite, which we will get to when looking into balance and control).

When making use of a story structure in the writing and designing of engaging and motivating experiences, you need to look beyond standard features of the dramatic story structures to access the motivating forces that form the core to the mood. The reason is you want to release the thinking and emotions from being framed by the end-state of a structure. As we go, you will see how the liberation fits very well by how the style of the game´s mechanics and systems work.

An example of a core to a mood that is based on the players´desires from earlier games can be found embedded in the mechanic of The Last Guardian (see Part 1, Putting into play, with interviews with Fumito Ueda). The forces constituting the core of a mood were collected from the relation between the player and the girl in Ico, and the bond between the player and the horse in Shadow of the Colossus that were transferred to the boy (the player) and the creature Trico in The Last Guardian.

Shadow of the Colossus, Team Ico, Sony Interactive Entertainment

Narrative systems

To discern the core of mood which captures the forces of the engaging and motivating drive, I will get underneath the story structure and remove the standards of start, end, acts, turning points, and conflicts and replace them with an engagement and duration-axis.

To explain how the engagement and duration-axis work, I will introduce the narrative systems behind the act of stripping the story structure in the first place.

The narrative systems are not the story but the systems that assist the structuring of patterns, which are based on the narrative principles of logic, time, and space (which I will return to later as they can explain what causes gaps).

The narrative keys of perspective, position, and goal presented in the previous section (see Part 6, Putting into play) represent the three narrative systems that constitute the cognitive process behind the creation of meaning. The systems that originate from David Bordwell's studies (Bordwell, 1985), also constitute the base to the method Narrative bridging (Boman, Gyllenbäck, 2010), which I am using in various forms depicting the hands-on approach to the design process (can be recognized from its color scheme).

The narrative system of syuzhet translated as plot (which term I will use) defines the constructor's perspective and position in the arrangement of causal, spatial, and temporal networks. The numbers of techniques on plotting are many, and my intention is to give you the base. The plot is not the story but the patterning of a story, or the patterning of gameplay (which I will get to later). The numbers of patterns that can be plotted are infinite. An example of one pattern is the canonical story format (exposition, complication, outcome). The pattern is a result of a long Western tradition of analyzing the assumptions of a canonic story. The canonical story format works as a template of developing story structures and where the three-acts story structure is just one variation of the template.

The plot system can't exist without the other system of style that mobilizes components and techniques provided by the medium and vice versa.

The plot and style systems prepare for a third system: fabula, which represents the receiver's perspective in the interpretation of the plot and style.

The reason why it may seem unclear from which perspective the rising, falling action, and the climax of the dramatic structure are taking place is that