This is the fourth in a series of game design articles about Puzzledorf. Originally posted on my blog here. You can see the full series here.

Playtesting is fundamental to Game Design. The aim is to observe people playing your game to so that you can identify areas of weakness in your design, or bugs, and methodically improve it. There are 3 keys I've found to help you playtest your games which I used extensively in playtesting Puzzledorf.

The Purpose of Playtesting

Before we get into the 3 keys of playtesting, I want to cover something I feel very strongly about. I feel strongly about it because I think that getting this right leads to better games, and to me this is the purpose of playtesting.

In game design circles, it's common to hear people say:

"You're not designing games for yourself. You're designing them for other people."

I believe that's only half true. I make games because I have a passion and a vision for an idea, and I won't be happy until I've brought that vision into reality. So from one angle, I'm making the game for myself because I want to play it. But I also want other people to share that joy. So I think the reality is you need to keep both in mind; yes, make it for yourself, but also remember it needs to be fun for others.

You can get too caught up in making a game you think is fun, doing all of the testing yourself, but forgetting to do product testing with actual customers. Then you release the game and find no one wants to play it. That's a bad situation, but I don't think the above statement is the solution. It could be interpreted as saying, "let the customers design it for you and change it to whatever they want." But do they always know what the game needs?

Your role, as a designer, is to observe people playing your game, and then decide what the game actually needs. Not every player will have the same opinion, so you have to decide what's best for your game.

I'm an absolute believer you should be designing a game you're passionate about, and when you do, great things are more likely to follow. To design a great game, I think you need at least one person who has a vision, and the passion and drive to follow it through to the end, keeping the team focused on that vision. How you get there might change, but don't lose sight of the vision.

But here's where it gets messy. You might have a vision, but you don't always know how to get there. This is where play testing comes in. I would rephrase the earlier statement like this:

"Design a game you're passionate about but don't lose the vision. Use other people to help you refine it."

It's an important difference. You're not getting playtesters to design the game for you - you should know what you want to achieve. But we can only know what's fun when it's in the hands of others, so we use playtesting to refine ideas. Otherwise you run the risk of, every time people play the game, you make whatever change comes out of their mouth, and eventually lose the original vision.

Puzzledorf is a good example. I knew I wanted to make a puzzle game, and I wanted people to push blocks. What I wasn't sure about was, "What makes a good puzzle?" So I used play testing to refine my puzzle design and to balance the game's difficulty, to make sure the design worked and was communicated properly to the player. My play testers weren't telling me what my game was; they were helping me to figure out where it worked, and where it didn't.

The 3 Keys

Observe

Test

Measure

This is similar to how you would conduct a science experiment. Game design can be turned in to a discipline with methodical rules to follow that, when combined with your creative ideas, helps produce consistent quality. Let's break down these rules for play-testing.

Observe

When I first started playtesting Puzzledorf, for a long time I just watched people play the game. I also refused to help them, as I won't be there to help a customer with the final product, so if you help them, it's not a true test. This led to many unique observations, helping me understand how people interact with my game, and I was able to identify potential area's of weakness from those observations.

Once I identified area's to work on, I then did further play testing for those specific elements.

Observing people use your game is a critical first step in playtesting. Your primary goal is to see if the game design works as expected. Start with general observations about your game and watch how people interact with it. See if anything stands out. Ask yourself questions like, "Are they playing as intended?" "Do they seem confused? About what?" "Is the game's objective clear?" "Is the difficulty correct?" "Is that ledge too high?" And so on.

As the game gets further into development, you should apply a more methodical approach and observe specific elements that need further testing and refining, which we'll discuss later in the article. An example, however, would be observing players attempt the jumps in a platforming game to determine appropriate heights and distances for those jumps.

In my puzzles, one thing I watched was to see if people could learn the rules of the game without my help.

Test

Testing comprises of two elements.

Initial tests and observations to identify weaknesses / bugs

Specific tests to refine key areas

The initial tests are part of that first observation, where people just play through the game and you see how the overall design is working.

The later tests are when you have made changes and are then testing it either on the same people or fresh players to see if the changes worked.

You should be testing every individual element of your game. Are there ledges to jump on? Test their height and distance. Do you have to kill enemies with a sword? Get players to attempt it. Do you have a shield to block bullets? Get players to block bullets. Are there special abilities and combo moves? Get players to try them.

Also, don't forget that you should be doing some of the initial testing yourself to work out early kinks, but don't rely on yourself as a play tester. Use others to help you refine the game.

Here's an example from an early proto-type.

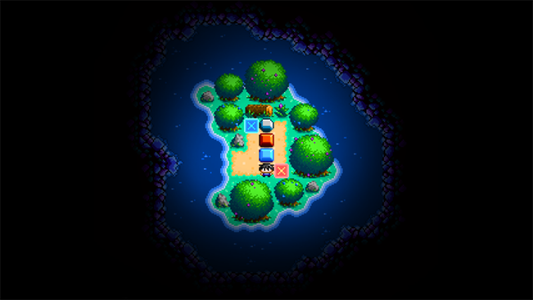

This was an early design for a level. I did some early play tests with others, and felt something was lacking. What I found was that, there were parts of the level that were never used, and the puzzle was more fun when I removed them. The parts in red are never used.

So then I redesigned the level like this:

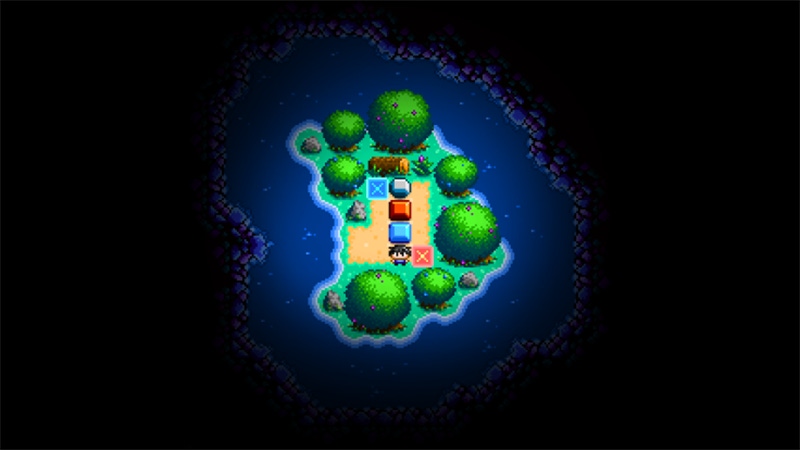

When I did that, people had more fun playing the game. In the end I decided the solution to that version was a little too obvious for my taste so I made further changes to the level. This is what it looks now like in Puzzledorf:

I flipped it upside down then made a few minor changes. Now every space is used. I talk more about how I refined my puzzles in my article onPuzzle Design.

Here's something else important to remember:

Every time you make changes, no matter how small, test them.

There is a game design theory called the wobbly jelly. The theory is this:

Every time you make a change, no matter how small, it wobbles the jelly (the jelly being your game). The more changes you make, the more the jelly wobbles, and the more likely something is to break. So often a small change, that seems like it shouldn't break anything, affects something small and completely unrelated.

I have experienced this myself many times. Usually I remember to test, but every now and again there's still something you miss, so be thorough with testing changes.

When you are testing, test as many people as you can. You might test a small group, make changes, then test the same group again to see if the changes worked, or you might test a fresh group. I like to keep people who haven't tried the game yet as a backup for someone I know will have a fresh experience.

With a puzzle game, for example, one person may find a particular puzzle very hard, even impossible, for some unknown reason, whereas on average the difficulty may be just right. The more you can test with the better, but 5 people is a good minimum to start with.

Make sure you tested every element of the game and that some people played through the whole game. This is particularly important for difficulty balancing. If only some players play the early levels and some players play the later levels, you don't have a consistent comparison of how a single player experiences the entire game. You need some players to do that to see how they progress through the challenges and difficulties. However, for small changes, do test specific components separately without always doing an entire play through.

Don't be precious with your idea's. No game is perfect on the first go. View each area that's not working properly as an opportunity to improve the design and make your best game yet.

Measure

This is really important but easy to miss. You might be tempted to just watch people, then make changes from memory. Don't do that. Instead, you should be recording observations and key data.

Have a writing tool nearby and jot notes as you observe the player.

If you're testing for specific and measurable things, such as, how many players died on level 3, or how long does it take each player to complete a level, record such things in an appropriate way. For level time completion, I would use a spreadsheet. Many things could probably be measured on a spread sheet, but a notepad or word document is also fine. Use whatever works, so long as you are tracking your data, which usually means tracking numbers.

How many people died at the waterfall in level 3? How many people died at the waterfall after you made changes? How many people passed the first level? etc.

With Puzzledorf, I balanced diffic