When we talk about a story-driven roguelike game, we neither only mean a video game with a mix of micro-narratives and a ludic loop, nor one that uses visual representations to convey an ideally coherent world. In fact, the most challenging claim in Children of Morta was bringing a plot-driven game together with gameplay that is mostly inspired by major elements of roguelike games.

As one of the designers on Children of Morta, who was added around the first quarter of the project, also the narrative designer and writer for the game, I will try my best to run you through our design process and the challenges we faced along the way.

1. Everything Starts with Family

Children of Morta (henceforth referred to as CoM) was born in 2014 (almost five years before its final launch) through crowdfunding; and like many of its peers that sought funding on Kickstarter, it too presented a basic idea that was almost oxymoronic, namely, a story-driven roguelike. But there was also the retro and stylistic art of the game that depicted the Bergson family in the midst of a fictional world where their adventures would take place.

Laying the Foundation

After funding was secured, it seemed like the game wasn’t going to be a mere roguelike or hack ’n’ slash. CoM owes a lot to pioneering games like Diablo. However, while Diablo set itself apart by breaking the genre norms to incorporate real-time combat and balance out permadeath, CoM tries to achieve the same by returning to some of its classic roots. We wanted to stand by our promises of delivering a heartfelt story about the Bergsons and at the same time revisit the core elements of rogue-like games. This meant that the players were going to experience the story in between the procedural levels and the Bergsons’ house. To this end, we required a form of permadeath for the playable characters, so the game had to flow without a checkpoint system.

Birth of the Bergsons

An important keyword used during the Kickstarter campaign was “family” and the fact that each of the main characters would be a part of it. This alone pushed our character development process a step above the class-character of RPGs. And since we needed the Bergsons to be a family, we had to portray their relationships in an authentic manner. This kept us busy well into the final months of development. Now let’s go over how the Bergsons came to be.

Initially, the game was supposed to be narrated in a book. So, players would see the book in-game and realize that they’re reliving the stories within it. The book would retell the story of total strangers who would unite around a central plot. They would meet each other in an inn and while there, something evil would occur forcing them to band together and go on a heroic journey.

But the Kickstarter campaign needed unique elements. Some of which were already made: In fact, our art style was reminiscent of impressionist palettes and most of our animations gave the player a certain “anime” vibe found in the works of Miyazaki. But what we lacked was something to hold together the narrative and the roguelike gameplay and emphasize this unique mixture. An element that would be our unique selling point. This was the concept of “family” which was the result of many a brainstorming session. The family angle was something that caught the attention of many of our backers; that’s how a narrative-driven roguelike centered on a family named the Bergsons was able to surpass its goal on Kickstarter.

Roguelike, Roguelite, Hack n Slash or ARPG!?

Using genres to define a game has always come with issues regarding their interpretation. You’ll be faced with definitions that don’t refer to a single, uniform essence. But that’s just how things are on crowdfunding sites, you can’t really avoid this model of presentation since, in the end, you have a game that isn’t finished and if you don’t have the prototypes to be showcased, you’ll need to introduce the game in ways people are already familiar with. So, these labels are actually handy when used properly. People are familiar with the bold characteristics of these definitions to a degree, even though each of them has been undergoing numerous changes during the last three decades.

ARPG was the first one mentioned. But that alone wouldn’t allow for the innovation we had in mind since there were already loads of ARPGs that were also narrative-driven. So we had to revisit the roots of the genre. But that didn’t mean using turn-based combat even though early roguelike titles did function that way. Also being narrative-driven or more precisely, story-driven was something that would directly contradict what defined a roguelike game which made this a pretty big deal and at first glance our initial design would be understood as that. That’s how we ended up adding permadeath and procedural levels containing random events alongside the story as the primary pillars of our design.

Morta needed serious Hack n Slash, but not solely be a Hack n Slash, as many of the previous ARPG titles before it were not pure Hack n Slash games but also delivered a story. The Hack n Slash element of the game was in fact a knob for us to adjust the complexity of enemy behaviors and playable characters within the combat system. It was clear from the beginning that we didn’t want to be a pure ARPG similar to Diablo and Titan Quest, nor a modern roguelike similar to The Binding of Isaac or Risk of Rain.

Procedural Levels

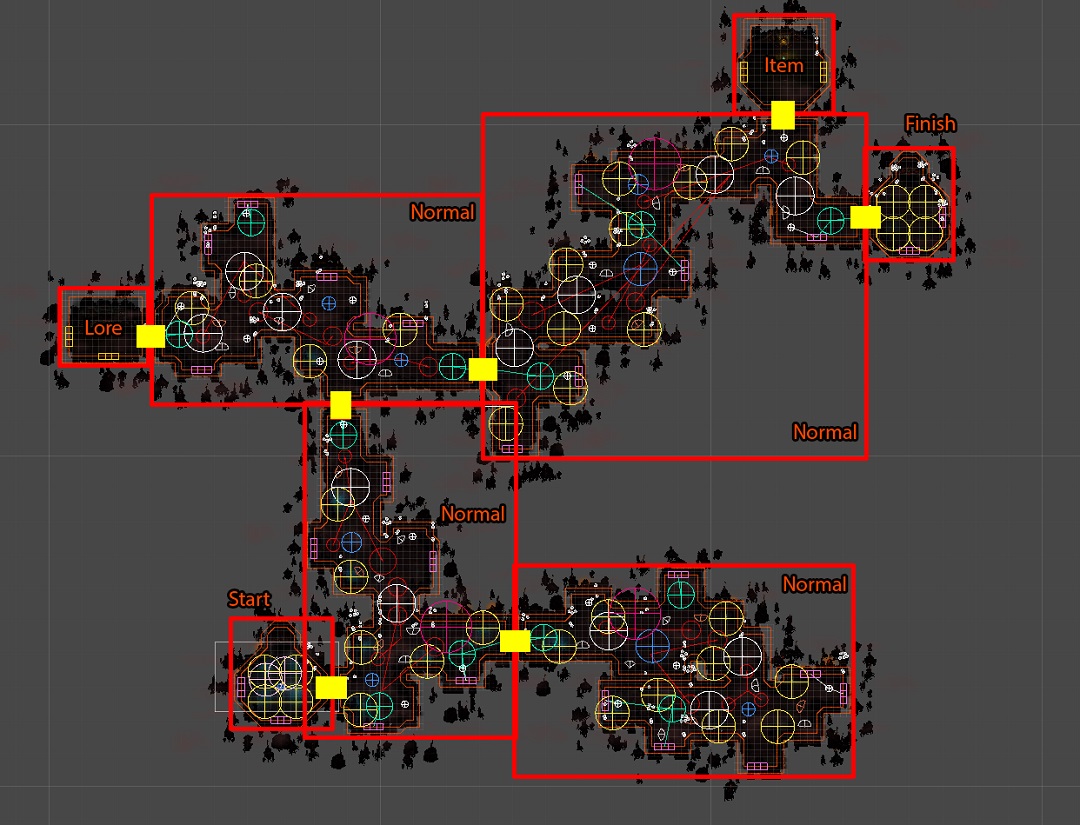

In CoM, the existence of procedural levels as a defining characteristic of the genre and also as a way of increasing variety and replayability can be summed up in three parts: creating levels with different geometries and visuals, spreading enemies in different ways across levels and finally chances of finding random items and power-ups. You also need to find a way to include micro-narrative events in-line with gameplay events. Even though your level design costs go down with this feature, the complexity and design challenges go up.

The initial level designs were fairly simple; one could even say they visually resembled the level design of early roguelike titles. The levels consisted of separate, predesigned rooms that were connected through machine-generated corridors. The spread of enemies throughout levels was uncontrollable. The enemies would spawn in random places within a room, aside from the corridors, without a predetermined pattern. So, their spawn patterns were unpredictable for the designers.

The visuals of the initial levels were made by placing ground and wall tiles in a grid formation. Right from the get-go, we noticed that the walls and ground were too flat and also the placement of the walls looked too bland. This was even more noticeable in natural environments. So, the decision to connect the walls to a tile before or after it was soon replaced with adjustable connections that can be even less than one tile. This feature gave us the ability to create a variety of geometric visuals that were not previously available in our initial prototype.

2. Challenges of the Initial Design

The initial game design was based on our promise on the Kickstarter campaign which stated that we would stick to 2 principles: one is dynamic gameplay and the other a narrative set around family bonds. This brought loads of challenges on board. In the case of gameplay, aside from issues pertaining to the number of playable characters and their different fighting styles, we also had to think of a way to create playthrough variation and think of a rewarding progression system. These were matters that were the subject of much discussion well into the final months of the project. In the midst of all this, our real issue was with the narrative, or rather the story; bringing together a story with this gameplay in a genre that historically has been without narrative was tough, especially when the story has a clear narrative arc.

Class Variation

In many past roguelike titles like The Binding of Isaac and more recently Enter the Gungeon, you have a distinct avatar as your playable character that doesn’t change throughout the game. Not being able to change your character is very efficient both from a design and an asset creation standpoint. But in CoM you don’t just do ranged combat like in Isaac and Enter the Gungeon, and your character variation isn’t similar to Risk of Rain and Nuclear Throne whose characters mostly differed in terms of their visuals. In fact, CoM was aiming to be similar to ARPGs like Diablo in this regard which had unique playable characters each portrayed in a meaningfully distinct way. This specifically made the design and asset creation more difficult.

In the Kickstarter campaign, we introduced six main playable characters that covered the scope of almost all the main classes in RPGs. From John who fights his foes at close range with his shield and sword to Lucy and Linda who are ranged damage dealers but we needed to make them distinctly different in terms of playstyle. Our efforts to make each character distinct can be seen in their design and visuals as well. Their abilities needed to be different in a meaningful way; their fighting style and visual cues during encounters needed to be taken into consideration so much so that the distinctness in fights required us to create many standardized behaviors for the enemies and bosses.

In the end, maintaining the meaningfulness of this vast cast of characters with their different abilities made balancing the game very complex and challenging. A challenge that kept us occupied till the end of the project.

How Should Progression Be Tackled

Almost from the start, we made the decision to make the Bergsons’ house act as the game’s hub. They were a family and the very least thing we could do to display that was to show them living together under the same roof. The Bergsons would go on missions and after every defeat or victory, they’d return to their home. However, this assumption had its own impact on the design of the whole game. From a narrative view, the house represented a place where family events would take place; from a practical view, the house needed to have an impact on the characters’ progression. So we created two functional sections that also fit the narrative well. Uncle Ben’s workshop and Grandma Margaret’s alchemy table were added to the house and were essential to the player’s progression. Uncle Ben would create combat equipment for the Bergsons which would permanently upgrade their character attributes; Grandma Margaret would create different consumables and the player would be able to carry a limited number of them for a run as temporary progression aid.

From the beginning, progression in CoM was focused on three main things: First, the player’s motor skills will adapt to their favorite character(s) which in of itself is dependent upon factors like getting over the difficulty curve, proper tutorials, etc. Second, permanent and temporary progression through collecting resources and power-ups, creating items and spending resources on upgrades either within the levels or at home. This type of combination had no place within classic roguelike titles. But something we were looking into during this time was an instant and unique progression in the form of power-ups that could be stacked to create variety with each run and even sometimes stumbling upon a random build that would allow the player to progress tremendously. Third, a narrative progression which the game’s whole flow depended upon. To be honest we didn’t know in what shape, where, in what order and how frequent story events should have been shown. What was obvious was that we needed to create a proper flow of challenges, rewards and narrative progression within the game.

3. How Did the Bergsons Become a Family?

When we were asked what the game we were making was about we usually said: “Well, it’s about a family” but as you can imagine that didn’t cut it. Imagine a Hack n Slash game but before you start the game, a panel pops out telling you: “The characters you’re going to play as are a family”, and the rest is up to your imagination to figure out how they’re related to one another; the feelings among them and what they’ve gone through. That is rather strange, don’t you think? Though maybe not that strange for a tabletop RPG, but Children of Morta wasn’t that kind of a game.

Around the time our Kickstarter campaign succeeded in reaching its goal, we were flooded with comments on what our backers thought the game could be, especially with regard to the family-centered aspect of the story. This shows that everyone had their own conception of what it means to be a family, and if our heroes were going to be part of a family then we had to at least do the bare minimum to fulfill that concept. This is where we made our biggest mistake: we didn’t pay nearly enough attention to this important theme for about 3 years. In fact, we didn’t do much else other than creating a half-baked family mood system and a number of brief character descriptions that showed their family relations. Our negligence continued until halfway through the project. That’s when we gradually started asking ourselves what we’d need to do to show they’re a family. More importantly, how would we be able to accurately represent those relations throughout our game?

Unlocking Characters Gradually

If the Bergsons are a family, which of their characteristics would need to stand out? Their altruism and sense of responsibility? Or their feelings for one another? Their disappointment in one another or their compassion and mercy for each other? All of these could be traits found in a perfect family. But we needed an “Other” to embolden this sense of family unity. So we came up with a unifying pattern; one which the Bergsons would unite over, learn to trust one another, lead them to sacrifice themselves in dire situations, and in the end defeat the corruption. This pattern provided a much-needed opportunity to have another go at characterization; in fact, each playable character would become playable due to the various narrative nodes created for them which would be used to introduce them.

This would also alleviate our concerns regarding the gameplay becoming repetitive and boring after a while since we would be able to introduce different mechanics to the player through the gradual unlocking of playable characters until the second chapter. With this in mind and together with the fatigue system, the player would be more incentivized to try their hand at different characters.

Representing Family Bonds through Gameplay

What impact have the family members had on each other? This was an important question for us since we were able to determine and highlight instances where their relationship can be emboldened. Some of the relations would be explored and represented through narrative means and at times through different gameplay systems.

We had a lot of different ideas on how to represent the family’s bond through gameplay. The Bergsons would be able to accompany each other on missions and even help each other out should they be in a pinch. Many of these ideas were visited and prototyped somewhere near the end of the project but were later scrapped due to the level of complexity in implementing them. Although, some of them were implemented in a more toned-down fashion.

Tagging Along with the Family

Among the various ideas to better cover the relations of the Bergsons, micro-events were designed for the in-run levels which showed the Bergsons cooperating with each other. Most of these events happened in a room. Sometimes one of the Bergsons would help another member, or help them in finding treasures or even accompany them when helping out NPCs.

The Bergsons’ continued existence alongside one another throughout the levels was a neat idea but the number of these events, while not too costly in terms of art assets, would be so high that we wouldn’t possibly be able to maintain the same level of meaningful quality other events had. So considering the very limited time we had, we decided to remove many of them altogether; very few of them made the final cut.

The Bergsons’ Spiritual Bond

One of the most crucial systems that was created in the game to represent family bonds was the Family Traits system the Bergsons shared with each other that would indicate their spiritual bond.

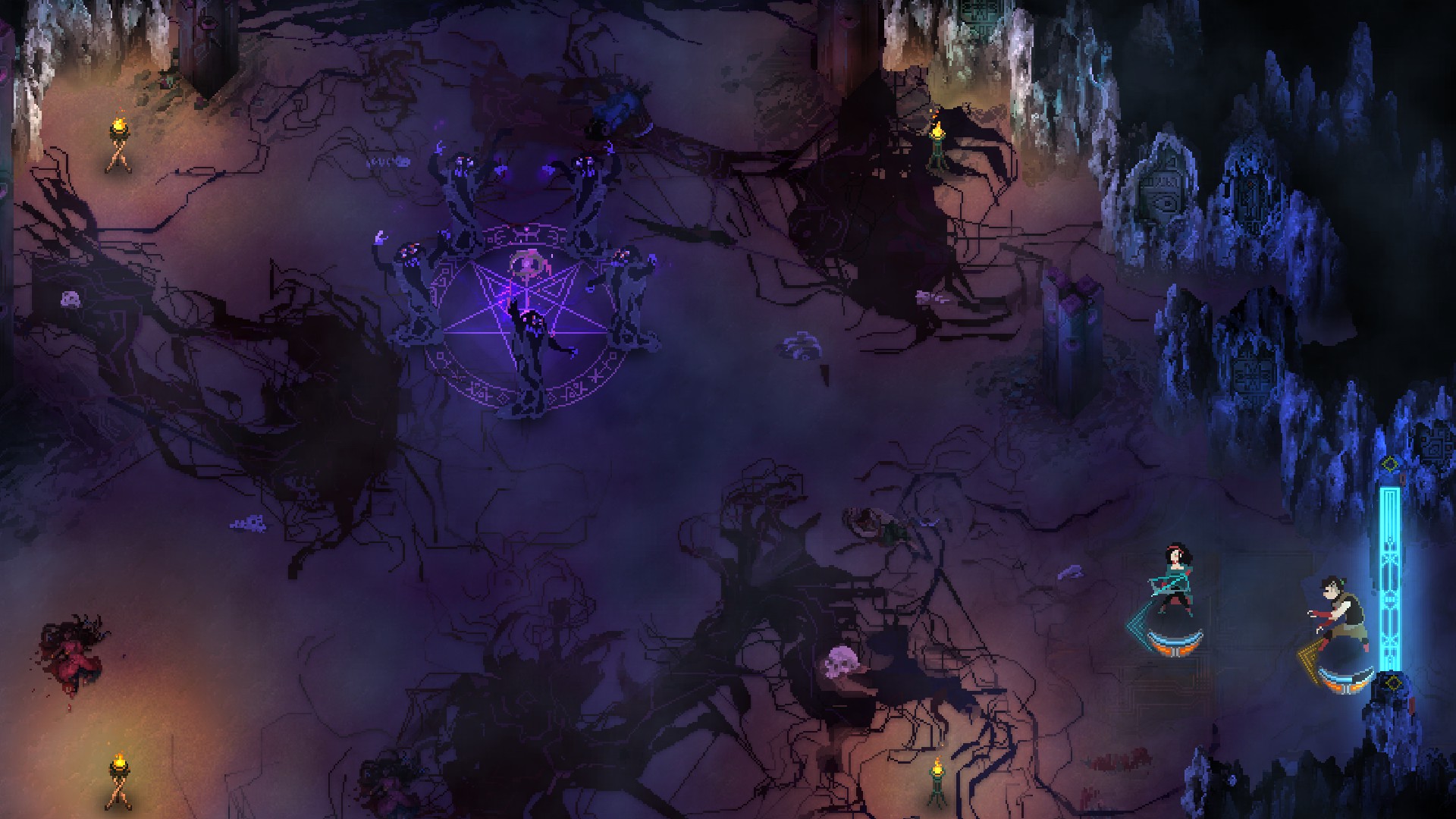

Initially, we were looking for a way for the Bergsons to come to each other’s aid. In the end, this form of aid was implemented in the game in two ways. First, they would be paired up during narrative micro-events and after it ended they would separate. But these micro-events were completely random and limited in terms of how many there were; also, the player didn’t have much control over them. The solution was that the family members would quickly come to each other’s rescue in critical situations. So technically, the Bergsons would be able to summon an astral projection of each other in the heat of battle.

This summoning feature was later turned into a separate system in the game; in a way, it tried to mix the game’s narrative with gameplay. In fact, we had come to the conclusion that if the Bergsons are able to summon astral projections of one another, they must have other spiritual effects on each other. These effects later became known as Family Traits and were placed in the Bergsons’ skill tree. Players would be able to unlock these spiritual bonds by spending more points in their skill tree which would be of benefit to all the Bergsons. To sum up, by progressing in their skill tree each Bergson would be able to transfer four traits that acted as buffs to their attributes to other family memb