Traditional 2D fighting games have problems, problems that most modern games have made every effort to avoid. To get only a chance to play a game they might be good at, newer players must surmount steep knowledge and execution barriers created from poorly structured tutorials, overly complex inputs, functionally nondescript control schemes, and an illogical lack of conveyance. While these issues impede learning and understanding, the intended audience of fighting games navigates around them through sheer hard work and determination. As such, developers aren't under as much pressure to implement solutions, leaving fighting games esoteric, something to be understood only by a specific audience. Over the years, some developers have partially or wholly solved these issues, but the rest of the genre has failed to implement those solutions consistently. To create fighters that, from day one, truly welcome and help newer players learn and grow in skill up to the higher levels of play, we need to acknowledge the issues and the solutions that have been attempted and work towards a new genre status quo.

Methodology

Most of the issues with fighters fall under the realm of usability. In their paper “Heuristic Evaluation for Games: Usability Principles for Video Game Design”, David Pinelle, Nelson Wong, and Tadeusz Stach define usability as “the degree to which a player is able to learn, control, and understand a game”. To assess usability within video game design, Pinelle, Wong, and Stach used a technique called heuristic evaluation. In this approach, evaluators test an interface against a set of usability principles. However, most video games don’t have principles for usability, specifically, so the three researchers read 108 PC game reviews from a popular website, noted and categorized reported usability problems, then distilled them into ten principles:

Provide consistent responses to the user’s actions.

Allow users to customize video and audio settings, difficulty, and game speed.

Provide predictable and reasonable behavior for computer-controlled units.

Provide unobstructed views that are appropriate for the user’s current actions,

Allow users to skip non-playable and frequently repeated content.

Provide intuitive and customizable input mappings.

Provide controls that are easy to manage, and that have an appropriate level of sensitivity and responsiveness.

Provide users with information on game status.

Provide instructions, training, and help.

Provide visual representations that are easy to interpret and that minimize the need for micromanagement (Pinelle, et al., 2008).

To illustrate how the esoteric design of fighters plagues the general audience, I will discuss issues with fighting games and tie them back to usability heuristic violations and other modern design principles.

Learning Aids

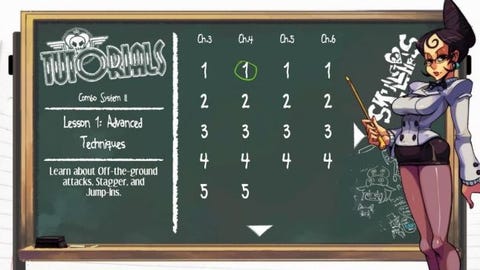

Most modern traditional fighters aren’t easily picked up and played at first by the general audience (TheBigBruce, Lee). A large part of that inaccessibility comes from high expectations and inefficient teaching. Traditional fighting games expect the player to be fluent in too many elements and mechanics to maintain control of the character. In the average fighter, the player needs to know how to, know when to, and be able to move, perform most of their attacks in a sequence, utilize multiple defensive mechanics, and adequately guard/counter their opponent’s options. If players are missing any one of those skills, they increase the risk of getting hit and having control of their character taken away via hitstun. In comparison, shooting games are much simpler and more forgiving, only requiring the player to know how to and be able to move, aim, shoot, and utilize any special abilities (grenades or ultimates, for example). Getting hit, in most cases, doesn't take autonomy away until the player dies. To help players, fighting game developers create a litany of tutorials that cover how to use the controls and mechanics. However, the ways in which fighters present their elements and mechanics are ineffective compared to modern standards. Fighting game developers throw one tutorial after another with little time to instill application. Even if the tutorials are extremely helpful, like in the case of Lab Zero’s Skullgirls with intricate breakdowns and demonstrations of all its systems, mechanics, and characters, the player must sit through, and possibly revisit, a plethora of them to learn the game (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Skullgirls has 7 chapters of 4-10 tutorials covering basic to advanced mechanics and character usage.

In games from other genres, designers lead players through experiences that intuitively incorporate the learning into the gameplay. Often with an on-screen explanation and the penalty of failure lessened or eliminated, mechanics are presented one-by-one with sections of the game dedicated to ensuring players master them before new mechanics are taught. In his paper titled “Learning By Design: Good Video Games as Learning Machines”, researcher James Paul Gee outlines a number of different learning strategies games can employ to help teach players. There, Gee mentions how humans have a hard time taking a load of soon-to-be-pertinent information in and applying it in the situations to come. He recommends games provide information “on demand and just in time” for better assimilation of the subject matter (Gee). Frontloading mechanics via a list of 15+ tutorials is, by comparison, archaic and inefficient at teaching mechanics. Players just can’t take on that much information at one time and reliably apply it later. Even if failure is minimized in these front-loaded tutorials, players would still benefit from more situations where they could be introduced to and test mastery of the mechanics in more bite-sized, engaging ways.

Take Ninja Theory’s 2013 reboot of Devil May Cry, for example. Being a combo-focused action game with a move-list and a training room to practice any of the moves at main character Dante’s disposal, one could argue that Ninja Theory didn’t need to include intuitive in-game tutorial sections, but they did. In DmC: Devil May Cry, when the player learns the base mechanics or acquires a new weapon with a pivotal function like breaking guards, the game pauses with a tooltip denoting the ability when it can be first-used and won’t resume until the player attempts that action (see Figure 2). Additionally, designers placed these sections in encounters with weakened enemies in bare minimum numbers, sometimes just being one enemy. Fighters could stand to do this. Players could fight an opponent that jumps in excessively, with the game pausing to show the proper anti-air timing, for example. This way, players learn what to do when the time arrives and how it applies to the moment-to-moment action, all within an engaging, potentially story-driven, experience.

Figure 2. DmC hits the jackpot with regards to teaching players.

Some fighting game developers do include mechanics specifically designed to help ease players into the experience. NetherRealm Studios’ Injustice 2 features a gear system with stats attached to equipment. Stats-wise, it functions like a handicap system, an intentionally lopsided stat increase meant to provide less skilled players the advantage in health and damage. While stat increases help make a more level playing field for players to learn on, they don’t directly help the player learn. In fact, it could be argued that it does the opposite; Increasing stats give players a reason not to learn, as it reinforces the behaviors they were previously doing. Why attempt to find higher damaging combos when you receive gear with better damage stats over time? Why learn to block your opponent when turning up the handicap setting increases your defense? With handicap systems, the player need only maintain that numerical stat advantage, trading in mastery of fundamentals and mechanics for number management.

In other fighters, primarily the flashy, movement-heavy “anime” fighters, “Simple” or “Stylish” control modes drastically lower the player’s need for perfect combo execution and knowledge of combo structure. While these help the player compete in the short term in a match, for the long term, they often don’t help them learn the game, namely the combo structure. “Stylish” control modes bypass player learning since most don’t allow the player to grow while using them. Most iterations of these Stylish systems assume the player doesn’t understand the combo and defense mechanics and compensates for that. For example, Arc System Work’s Blazblue: Central Fiction’s Stylish mode does two things: It maps special attacks to a single button press, which smartly eliminates the need for complex inputs and universalizes key special inputs across all characters, and it also converts the player’s normal attacks into full combos if they keep pressing any attack button. This seems to be a good approach, except this conversion keeps happening even if the player learns their own combo and tries to input it. This means Stylish and “Technical”, the normal/traditional input system, has no middle ground when it comes to normal attacks, the main combo filler. Despite being a system designed to help beginner players, Stylish having no middle ground makes learning difficult. Assistance mechanics and systems should make learning easier and let the player grow with them in every capacity without needing to turn them off to apply basic lessons learned.

Along these lines, a system like Blazblue’s Stylish system, with auto combos off some or all inputs, would be more ideal for player learning if instead of converting from any pressed consecutive button it converted into a combo only if the same input was pressed more than once. That way, if the player realizes that, let’s say, their standing medium attack (M) confirms into their standing heavy attack (H) but doesn’t know the rest, they could input MH then continue to input H for a full combo conversion. The more conversions players learn from intuitive playing, the less they need the system, until they don’t need it at all or can capitalize upon what it has to offer. Arc System Works seems to have caught on to that design philosophy in their game Dragon Ball FighterZ. The popular title employs auto combos off two of its three attack buttons, replete with air versions, super conversions, and the ability to cancel them into one another. Most players abandon auto combos in favor of more optimal combos once they reach the intermediate levels, yet, the system remains intact for players to use.

Complex Inputs

Of course, alternate, simplified combo systems and control schemes wouldn’t be necessary if the execution barrier for most fighters wasn’t so high. Fighting games have the player pressing a lot of buttons, the most difficult being complex inputs involving multiple directional inputs and then a face button press for special attacks and supers. For example, to perform a standard Fireball, players traditionally must move the analog stick a quarter circle forward and press a punch button. These complex inputs were initially, and ingeniously, made to allow more moves, and subsequently more gameplay options, to be put on characters in the original Street Fighter, which was limited to the 6-button and 1 joystick arcade cabinets (Leone). However, from there, developers made the movements more complex to balance and include more powerful moves, leading to nasty inputs such as pretzels and full circles. Making inputs with high possibilities to fail for balance’s sake essentially blames the player for the developer’s design decision to make a move powerful, violating the usability heuristic of “intuitive input mappings” (Pinelle, et al). Although the timings have become much more lenient over the years, the idea that some players are expected to fail for attempting something good still exists in some moves such as Iron Taeger’s double full circle command grab super in Blazblue: Central Fiction. To help alleviate input complexity for balance’s sake, developers should find other ways to balance powerful or effective moves.

Note, however, that simplified inputs may prove too risky for some games as it will change the pace and style they have built over the years. In those cases, the answer might be to simply remove any input more complicated than a half circle, with double quarter circles being the only exception. I’ve seen most newcomers execute quarter circles easily and implement them into their game plan with little practice. Half circles, while not the easiest input, would then round out the needed inputs for a fighter as the traditional command grab input. Alternatively, in place of half circles for command grabs, quarter circles plus the use of the throw button can be used for a more consistent throw functionality, as seen in AOne Games’ Omen of Sorrow.

Going forward, developers should try to avoid using overly complex inputs. Inputs like full circles, pretzels, and triple complex combinations of halves and quarters are too complicated and heavily violate good usability principles. For the simpler complex inputs, developers could take a page out of NetherRealm Studios’ book and let the player toggle between traditional and simplified complex inputs. In NRS games, simplified, “Alternate Controls”, remove diagonals from complex inputs, turning quarter circle back into down back or a half circle into back forward, for example. With as many complex inputs as there are in the average fighter, an optional alternate control scheme just addressing them can always help.

Redefining Intuitiveness

While the problem of ease of understanding and use can be solved largely through restructured learning sections and more lenient input systems, intuitiveness, or ease of learning through use, of the gameplay systems presents a much larger hurdle. Reviewers seem to like to use the word “intui