Abstract

This article discusses an approach to make more interesting and pleasurable hyper-casual games. The aim is to achieve both higher retention rates and lower CPI numbers for hyper-casual games. The article discusses general approaches to design interesting games, and then projects that knowledge on hyper-casual genre by considering its peculiarities. It is based on several psychological experiments presented by professor Daniel Kahneman in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow [1], who received the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for his pioneering work with Amos Tversky on decision making.

Introduction

Today hyper-casual game genre is very popular among players and game developers. Although there are predictions that the market is shifting from hyper-casual to hybrid-casual games [2] but this does not mean hyper-casual games are dying. This means the genre is actively transforming and evolving. Nowadays there are hundreds of game development studios and teams that make hyper-casual games, and dozens of publishers who offer hyper-casual game publishing services. Therefore, it is critical to analyze and understand the reasons behind successful titles.

So why some games succeed and make to the tops and others - don’t? What key points we might miss while making a game - hyper-casual games specifically? Why are some games good, but they never make that important transition from good to great?

In 2008 the App Store was born. There was a time when people could make a game or an app overnight and earn money. In 2017 App Store featured over 2.1 million apps [3]. At that time App Store was already so saturated and the competition for exposure and attention was so high that developers had to work long and hard on their games and also had to get significant download traffic obtained by marketing or store featuring to hope for something. It looked like those dream days were gone, when small teams with very small budgets had a chance to succeed. But, fortunately, life is not linear.

In 2017 Voodoo significantly contributed to popularizing hyper-casual genre. Although Voodoo didn’t pioneer making hyper-casual games, it took a couple of important steps towards establishing the genre: it understood customer needs, created design guidelines for the genre, a successful marketing and monetization scheme, named that genre and started to educate development studios how to make good hyper-casual games. Soon also created a dashboard where hundreds of studios can test their games quickly and transparently. The latest is also a big step forward, as even today some well known publishers test a game’s KPIs and hide from the developer what creatives have been used for testing or even hide the CPI numbers by giving a vague information.

Pioneering of hyper-casual games is usually attributed to Ketchapp, sometimes people argue that this is not a new genre, this is just the renaissance of arcade games of the 70s [4]. But in this context it is not important when the first blossoms appeared. It is important that thanks to Voodoo in 2017 hyper-casual genre has become a well formed and established genre and captured the top charts of US App Store.

This was really a second breath for small game studios like us to get back their hopes to make small games and earn a significant amount of money [5,6]. Soon many other publishers joined the new trend and offered publishing services for hyper-casual games.

Today, only 2 years later, hyper-casual game market is estimated at about 2.5 billion in annual revenue. There are hundreds of millions of dollars invested in hyper-casual games, [6] and dozens of well known and unknown publishers are looking for game development studios.

But how much game studios are in control of making hyper-casual games? Are they rolling the dice or professional game designers are able to craft the desired experience for the audience and make a hit game for the market? One particular problem with hyper-casual games is that those are so small and so simple that usually it is hard to understand how it is possible to apply the historically accumulated game design knowledge to such games [7]. One of such knowledge is the concept of interest curve. In this article interest curves are discussed and it is explained how a game designer can make his game more interesting even when the game is very small.

The Interest Curve

Jesse Schell in his book The Art of Game Design discusses an interest curve of an entertainment experience [8]. Interest curve is a simple concept - it is the dependence of the customer interest over time while consuming the entertainment experience.

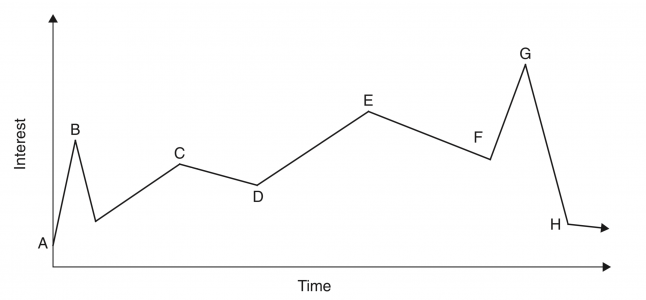

In that chapter Jesse Schell tells a very exciting story. At the age of 16 he started his career as a professional entertainer in an amusement park. One day the head of his show troupe, a magician named Mark Tripp, has taught him how the interest curve of a performance should be. Namely, he taught that keeping the same content (events) but re-ordering them might significantly enhance the quality of the experience for a magic or juggling show. Based on that advice Jessie Shell describes a good pattern of an interest curve of a well thought entertainment experience (see Figure 1 - taken from the book).

Figure 1, An example of an interest curve for a successful entertainment experience

The main takeaways from this graph are that:

The customer (game player, theme park guest, movie/theatre customer) comes with some initial non-zero interest, maybe because of the Ads, or because of friends’ referrals (point A).

As an entertainer, during the first moments you need to increase his interest in order to create some expectations for the whole show. This is called “the hook”. (point B)

Later there should be no flat part on the interest curve, because otherwise the consumer may leave the experience. The interest should rise and fall, but only to rise again (points C, D, E, F).

The last part of the experience should be the grand climax. This is where the experience should become the most interesting and this is where the story is resolved (point G). It is desirable that the customer leaves the experience with some interest still left, in order to return again. Jesse Schell mentions that the leftover interest is what show business veterans say “leave them wanting more” (point H).

This is a very important lesson for a game designer to know how to order interesting moments along the experience timeline.

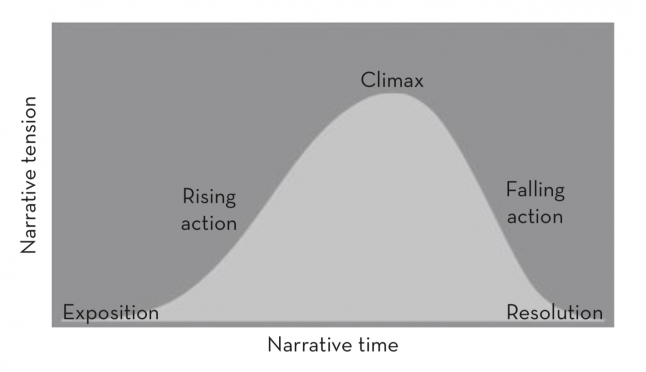

This topic is also discussed in “Game Design Workshop” [9]. Tracy Fullerton describes how a classic dramatic arc is constructed (see Figure 2 - taken from the book).

Figure 2: Classic dramatic arc

It all starts with an exposition, where the consumer gets acquainted with the characters, the situation and the initial conflict, i.e. the premise. This creates a tension for the consumer to engage and wait for its resolution (the hook). This is a psychological phenomenon called Need For Closure (NFC) that describes “an individual's desire for a firm answer to a question and an aversion toward ambiguity” (from Wikipedia). [10]. The further development of the plot is being done by escalating the conflict. At some point the tension is on its maximum - the climax point. And then the resolution follows where the built tension is released.

So, basically, this is the same concept - no matter how you call it the interest curve or the dramatic arc.

But what if I make a hyper-casual game? There is no story, no plot, a very small amount of narrative is present - if present at all. How can we use this very important knowledge in hyper-casual games?

What does psychology teach us?

To understand what tools we have to operate with player’s interest in the scope of hyper-casual games, we need to understand some psychology. Here I will refer to results described by prof. Daniel Kahneman in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow. In this book he writes about many-many concepts and experiments that are directly useful to game designers. Those experiments are covering many important aspects of decision making, and game designers must know about those experiments for the following reasons:

While making games we make decisions, and we need to understand what hidden forces may act on us while we make our decisions.

While making games we work with a multi-profile team, with diversity of opinions and ways of thinking. We need to understand how our colleagues make their decisions, and how we can help them make better decisions.

While playing a game a player needs to make decisions. If the player does not make decisions while playing a game, the game playing is becoming a static content consumption such as a book or a movie consumption is [11]. Hence the designers should understand how players make decisions and nudge them to make better, more pleasurable ones. As Sid Meier once said, we need to protect the players from themselves [12].

In the following 2 subtitles I will present psychological experiments that, hopefully, will change your attitude towards game development forever. I strongly recommend reading the book Thinking, Fast and Slow, if not the whole book then at least Chapter 35 “Two Selves”, to fully understand the obtained results. Here I will summarize the main details only and cite some experiments from the book. We will learn about two concepts - Peak-End rule and its generalization Less Is More rule. Let’s examine them one by one starting with Peak-End rule.

Peak-End rule

Prof. Kahneman wanted to understand how people experience pain (or pleasure) and how they remember them. For that reason, during experiments they were measuring the intensity of pain of colonoscopy patients. Back then when they were doing those experiments, colonoscopy was not administered with an anesthetic as well as an amnesic drug and was painful.

Citing from the book:

The patients were prompted every 60 seconds to indicate the level of pain they experienced at the moment. The data shown are on a scale where zero is “no pain at all” and 10 is “intolerable pain.” As you can see, the experience of each patient varied considerably during the procedure, which lasted 8 minutes for patient A and 24 minutes for patient B (the last reading of zero pain was recorded after the end of the

procedure). A total of 154 patients participated in the experiment; the shortest procedure lasted 4 minutes, the longest 69 minutes.

Next, consider an easy question: Assuming that the two patients used the scale of pain similarly, which patient suffered more? No contest. There is general agreement that patient B had the worse time. Patient B spent at least as much time as patient A at any level of pain, and the “area under the curve” is clearly larger for B than for A. The key factor, of course, is that B’s procedure lasted much longer.

When the procedure was over, all participants were asked to rate “the total amount of pain” they had experienced during the procedure. The wording was intended to encourage them to think of the integral of the pain they had reported, reproducing the hedonimeter totals. Surprisingly, the patients did nothing of the kind. The statistical analysis revealed two findings, which illustrate a pattern we have observed in other experiments:

When the procedure was over, all participants were asked to rate “the total amount of pain” they had experienced during the procedure. The wording was intended to encourage them to think of the integral of the pain they had reported, reproducing the hedonimeter totals. Surprisingly, the patients did nothing of the kind. The statistical analysis revealed two findings, which illustrate a pattern we have observed in other experiments:

Peak-end rule: The global retrospective rating was well predicted by the average of the level of pain reported at the worst moment of the experience and at its end.

Duration neglect: The duration of the procedure had no effect whatsoever on the ratings of total pain.

You can now apply these rules to the profiles of patients A and B. The worst rating (8 on the 10-point scale) was the same for both patients, but the last rating before the end of the procedure was 7 for patient A and only 1 for patient B. The peak-end average was therefore 7.5 for patient A and only 4.5 for patient B. As expected, patient A retained a much worse memory of the episode than patient B. It was the bad luck of patient A that the procedure ended at a bad moment, leaving him with an unpleasant memory.

Prof. Kahnemen explains that we have two selves - experiencing and remembering, i.e. we experience a process differently than we remember. Now the question rises, which self is deciding? If there will be a choice for us, which experience we want to repeat who will decide - our experiencing or remembering self? Prof. Kahneman explains that the decision-making power is in the hand of our remembering self and here is a clear experiment to demonstrate that. Again citing from his brilliant book Thinking, Fast and Slow.