Virtual reality has had a shaky 18 months. After years of hype about the world-changing potential of its second coming (following a dud first wave in the 1990s), its poster child headset the Oculus Rift launched to a lukewarm reception. Other high-profile headsets — Rift's high-end PC rival, the HTC Vive; Sony's PlayStation VR; and Samsung and Google's mobile rivals, Gear VR and Daydream, respectively — have sold better, but still consumer takeup remains modest.

Sony reported in June that PlayStation VR has sold over a million units since its launch in October, while tracking firm Superdata puts Gear VR's installed base at 8 million and Vive's at around 670,000. The Vive is reportedly outselling the Rift by around two-to-one, yet now HTC is considering selling off its Vive division. And after the Rift's July price cut, HTC and Sony have now followed suit, prompting speculation that VR sales across the board might not be meeting expectations.

We reached out to a few leading VR game devs to get their take on where things are at right now for the technology, and to find out if they think there's any basis for rumors of its impending demise.

The trough of disillusionment

"Technology getting cheaper is usually a sign that they're advancing, and that the market is good," notes veteran designer and former Disney imagineer Jesse Schell. His company released the well-received-but-possibly-not-yet-profitable VR title I Expect You To Die, and he says he sees no problem with the sales figures so far.

"This is what happens with every technology. People who don't know anything about that technology overinflate the impact that it's going to have, and then when it comes out they're angry because it didn't meet their expectations."

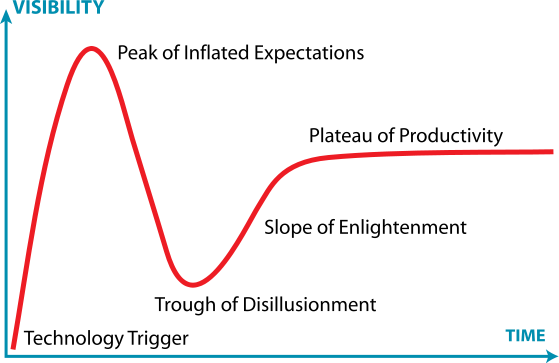

Many VR insiders cite research firm Gartner's hype cycle graph as evidence that everything's fine. The graph shows that new technology routinely enters a "trough of disillusionment" after a period of inflated expectations. VR is currently in or emerging from its trough of disillusionment, and if it follows the graph it'll soon move onto the "slope of enlightenment" where the technology matures and then it'll hit mainstream adoption.

"This is what happens with every technology," says Schell. "People who don't know anything about that technology overinflate the impact that it's going to have, and then when it comes out they're angry because it didn't meet their [uninformed] expectations, and then gradually their ignorance comes in line with reality and people figure out what the technology is actually good for."

It happened with the iPad, which has found its place as a lightweight computing device, and it happened decades before that with the personal computer. In fact, VR's current trajectory has much in common with personal computers. "In the 70s when the Apple II came out and the Atari 800 came out," says Schell, "they were priced at something like $1500-2500 and everyone said 'wow these are really cool but who can afford this?'" Sales were initially low, confined only to the true believers and curious affluent people.

" VR has the ability to affect so many industries. Yes, gaming and entertainment, but also training and simulation, real estate and enterprise, and cognitive therapies."

Soon nearly every technology company was releasing their own personal computer, with dozens of short-lived failures coming and going before anybody had even heard of them. But great software and cheaper systems emerged gradually, and computers were mass market by the end of the 1980s — a decade in which the Commodore 64, Amiga, Apple II, Mac, and IBM-PC each sold millions of units.

Just as it did in the 1980s for the PC market, when a few platforms rose to prominence and the rest faded away, Schell expects the VR industry will settle down "once some people start making the right moves and somebody gets the right combination of price and features. Then they'll start to dominate and all those others will fall away."

Sometimes there are exceptions to this technology adoption curve, like 3D TVs, that go crashing down from hype to flop, but Owlchemy Labs studio director Cy Wise says VR is safe from that kind of failure. "The problem with 3D television is it basically only did one thing and no one really found its reason for existing, whereas VR has the ability to affect so many industries," she says.

"Yes, gaming and entertainment, where we tend to hang out," Wise notes, "but also training and simulation, real estate and enterprise, and cognitive therapies."

Schell Games' I Expect You to Die

Platform opportunities

"Less than 10 percent of the VR games out there made more than $250,000. So that's about what you can spend to make a VR title and bring it to market and hope to at least make your money back on it. "

Schell, whose studio Schell Games has released games for nearly every VR headset (including two on Daydream and one on Gear VR), says that the bulk of opportunities for VR devs currently lie on PC and console, as mobile is not only "incredibly hard to do anything profitable on" but also much more limited, technically speaking.

Furthermore, the VR market right now lends itself best to small teams with modest budgets and year-long schedules. "This is just Steam Spy's numbers," notes CloudGate Studio co-founder Steve Bowler: "Less than 10 percent of the VR games out there made more than $250,000. So it's kind of like, that's about your budget — that's about what you can spend to make a VR title and bring it to market and hope to at least make your money back on it."

Schell guesses that at least 90 percent of VR titles produced so far are not yet profitable. "But that is kind of natural given that we are on the thin end of a growing wedge," he says. "And so I think anyone who looks at this as if it's a normal triple-A industry where you make most of your money in the first three months of release of your title is going to be sorely disappointed."

Cloudgate Studio's Island 359

Slow and steady

" I think it's hard to disagree with the transformative power of VR once you've experienced it for yourself. That doesn't mean people are going to be able to afford it right away."

The smart money, instead, is in making a long-term investment — to put a bit of money in early so that your studio can learn the technology, get in on the ground floor of what will eventually be a significant market, and begin fostering a VR-specific community.

Or as Schell puts it, "if you're not ready to take that long view you're going to run out of runway and be in trouble." Growth will be slow and steady, not explosive, which Schell points out is perfect for a pervading trend across the games industry at large: that of games as a service, supported and expanded for years after release, rather than a product.

Bowler thinks VR naysayers are a dying breed. "I was one of those naysayers for a long time," he says. Google Cardboard and both Oculus Rift devkits made him sick, but then he was strong-armed into trying the Vive — because as creative director he needed to know the tech in case they had a work-for-hire opportunity. This time he came out a VR convert, convinced his sci-fi tech dreams were becoming a reality. Now he calls it "being is believing."</

No tags.