Copyright ©2017 Chris Solarski (SOLARSKI STUDIO)

My second book was recently published by CRC Press. Titled, Interactive Stories and Video Game Art, I'm very proud that it has been described as gaming's equivalent to Story, the classic book on screenwriting by Robert McKee, and endorsed by film director, Marc Forster. This article—kindly sponsored by the SAE Institute Zurich—explores a key concept that I developed in the book called the unreliable gamemaster. This article concerns the dramatic value of player-character motivation and in story-driven games. The featured case studies illustrate techniques for adding a second narrative layer to game objectives, and how this layer can heighten player immersion.

SPOILER ALERT: before proceeding, readers should be aware that the article contains spoilers for the following films and games: Wreck-It Ralph (2012), Halo 4 (2012), Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End (2016), The Beginner’s Guide (2015), Firewatch (2016), Gone Home (2013), and The Usual Suspects (1995).

Want vs. Needs

Making a distinction between a protagonist’s wants and needs is a basic consideration for anybody who has studied screenwriting. To paraphrase artist, writer and filmmaker, Iain McCaig:

“Someone has a want, but obstacles must be overcome to achieve that desire, with the toughest being a hidden obstacle inside them (their need). In the end, the protagonist gets what they need but not necessarily what they want.”

Wreck-It Ralph’s greatest obstacle is overcoming his material want and realising his spiritual need in Wreck-It Ralph (2012), Walt Disney Pictures, directed by Rich Moore.

These motivations (wants and needs) are aptly illustrated by Wreck-It Ralph, directed by Rich Moore. The film makes for an interesting reference for the way in which storytelling is generally handled in games because it’s a satire of game design tropes. In a world where good is always good and evil is always evil, Wreck-It Ralph, a villain, dares to defy convention and become a hero. This want, he dreams, can be achieved by winning a medal. However, at the end of the film he overcomes his biggest obstacle, himself, and learns to become selfless and care for others—the true traits of a hero—which he achieves by helping Vanellope von Schweetz win a medal. This final show of empathy is Wreck-It Ralph’s hidden need, which gives emotional value to all his preceding, self-centred deeds. Based on this example we can refine our concept of wants vs. needs with the following statement:

Want (material) vs. Need (spiritual)

This is a general theme of most stories in film and literature because the internal conflict between a protagonist’s wants and needs is a powerful catalyst for overt drama—adding depth to a simple risk-and-reward narrative structure. You can also reference The Matrix (1999) and Neo's want to remain a regular guy versus his need to accept that he's The One; or Jaws (1975) and chief, Martin Brody's, want to catch the killer shark versus his need to confront his fear of water. If a narrative focuses too much on fullfilling the want and not enough on the need, the audience will perhaps experience visceral gratification, but little spiritual fullfillment. In game design we must also acknowledge the wants and needs of the player when structuring a story. The motivations of the player and playable character need not be the same but the intended aesthetic experience should align if the story is to deliver its intended message. I will therefore refer to both the player and playable character as the player-character—a single entity—wherever applicable.

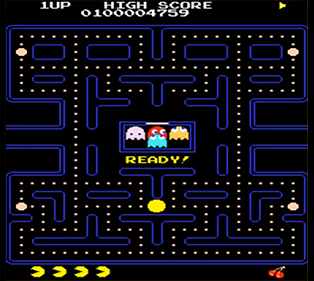

The overachieving gameplay objective (the player’s want) in PAC-MAN (1980), by Namco, is clearly depicted atop the screen.

The Reliable Gamemaster

Classic video games like PAC-MAN (1980) have a fairly simple task of aligning the motivations of players and playable characters. We must assume that Pac-Man wants to avoid ghosts and stay alive. The want of players is usually reflected in gameplay objectives—the overarching task players are given to perform. Objectives in classic games tend to be communicated through the user-interface (UI). PAC-MAN’s designer, Toru Iwatani (1955-2017), boldly stated the game’s overarching objective by inserting the word “HIGHSCORE” and an accompanying counter at the top of the screen. This objective is clearly a material want that encourages players to keep Pac-Man alive to better their score and jostle for the #1 spot on the leaderboard. While the player’s need—the hidden obstacle inside the player—is the time and dedication needed to master PAC-MAN’s gameplay.

The dialogue between a game’s designer and the player—as illustrated by PAC-MAN—is deliberately straightforward. PAC-MAN is a formal game so the objective of play must be communicated clearly if players are to understand the game's rules and objectives and respond with correct inputs to win. The purpose here is pure play from which emergent stories are generated ("I was cornered by Pac-Man Ghosts but just managed to escape through a tiny gab!"). If a scripted narrative features in such a game it is merely a wrapper. The narrative could be interchanged with any other and the emergent stories would remain largely unchanged—such as the stories that emerge when playing Chess with medieval-themed versus Star Wars-themed pieces.

Echoes of this structure that consists of formal gameplay with a narrative wrapper is evidenced in many contemporary story-driven games, even though gameplay has a different status compared to games like PAC-MAN. In the case of story-driven games the narrative should dictate the shape of gameplay—not serve as a mere dressing—if the intented dramatic experience is to be evoked.

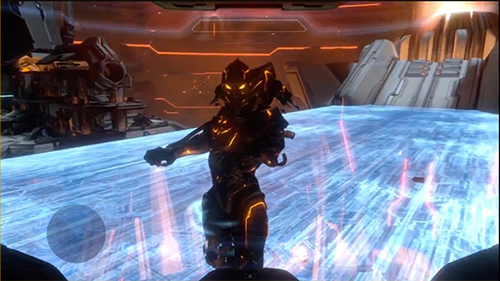

In Halo 4 (2012), by 343 Industries, the AI companion, Cortana, serves as the game designer’s mouthpiece—communicating a breadcrumb trail of objectives that players must overcome.

Take for instance Halo 4, which features Cortana—the player’s AI companion in the single player campaign. Cortana serves a similar purpose to a narrator by providing backstory and tactical information. More importantly, in the context of this article, she serves the same function as Iwatani’s “HIGHSCORE” because we can likewise perceive the game designer’s disguised voice when Cortana gives commands such as:

“They found the opening. You better get up to that relay, and fast.”

“Power core down. Shield’s weak, but still online. Take out the other two power cores and we can access the pylon.”

“Second power core offline. Good job, Chief.”

[…and so on.]

The