,

,For all its disruption, political instability and economic turbulence, 2022 was a year that showed just how much the games industry continues to defy world events, with a generation of consoles that still couldn't meet demand even after a price hike and unbelievably expensive graphics cards that nevertheless sold out in minutes. The number of gamers worldwide has continued expanding rapidly, bolstering the industry’s place as the largest entertainment sector by a wide margin. But all this growth is making it harder to ignore the wider context in which games are created and played. Perhaps the most pressing example of this is how much energy and materials go into manufacturing, shipping, developing and playing games on all the devices we use, and the unavoidable impact on the environment that entails.

In the last decade there has certainly been progress drawing attention to environmental issues in the world of gaming. Many well-researched articles have been written, alongside a number of academic papers. An organisation called the Playing for The Planet Alliance was set up in 2019, partnered with the UN Environment Programme, to better enable the industry to spread environmental messages via the medium of games while also helping companies in the industry monitor their own impacts.

The Alliance then launched the Green Game Jam in 2020, encouraging developers of all sizes to incorporate environmental content into updates for their existing games and offering awards in several categories for their efforts. In 2021 the Green Games Guide was released, a handbook of tips, ideas and instructions for how businesses can reduce emissions across all areas and operations. There’s also a Special Interest Group with its own discord server, seeking to bring more coordination to grassroots movements in the industry.

Journalist Jordan Erica Webber sets off the 2021 Green Games Summit, an insightful set of talks which far too few people have watched

But the caveat is that so far, these efforts haven’t caused a major dent in the environmental footprint of the industry as a whole. And that's a problem because worldwide, video games use up a lot of energy, resources and labour. Below, I will set out the case that we need to think bigger, ramping up the pressure on the most powerful companies in our industry, if we are to achieve meaningful reductions in energy use and other environmental impacts in a limited window of opportunity.

Breakdown

A helpful first step is to provide some context on just how big the games industry has now become in 2023. On the player side, the total number of active gamers is estimated at 3 billion, over a third of the human population. Of the roughly 4 billion smartphone users, 2.5 billion play games on them. PC gamers total 1.8 billion and there are perhaps a few hundred million console gamers. (These estimates all need a pinch of salt because different sources give figures that vary by hundreds of millions, as is expected for such a vast and growing sector.)

Industry numbers are equally difficult to estimate globally, given the wide array of workers who are both directly and indirectly employed, alongside freelancers, students, hobbyists and so on, making it unclear how to pin down a determinate figure. Depending on how widely the industry is defined, the total number of workers could be anywhere between a few hundred thousand and a few million.

Carving up the production cycle across all devices into more refined categories is another big task, as video games sit at the end of a long and complex chain of economic activity. Just some of the steps required to bring you that huge update for the new game you had to wait patiently to download on Christmas day include: resource extraction, device manufacturing, packaging, shipping, online data centres, developing the game itself, producing the disc if it came on one and supplying household electricity from the national grid. All of these in turn require the building and maintenance of a large web of supporting infrastructure.

Each step has not just its associated energy requirements, but also a material footprint comprising all of the metals, plastics and other physical stuff required to mine out of the ground, assemble the platform device, transport it around and make it possible to play games on. The full impact of a product on the world, including both the creation process and eventual disposal, is known as its Lifecycle Assessment. While it can be tempting to jump straight to the burning of fossil fuels when tallying up the environmental costs of anything that uses energy, materials usage is a critical factor which is not easy to compare in an apples-to-apples style to any particular quantity of carbon dioxide released into the air. Some investigations have been made that tackle both aspects of device footprints, such as this one from the Verge on the PS4.

With these factors in mind, we can start to consider how things break down, area by area. It’s clear already that the answers will vary a lot based on the hardware required for each platform, install bases and types of games developed. For example, small devices like smartphones and portable consoles have low power requirements and tend to be replaced frequently, making them likely to have embedded emissions (those required for manufacture, transport, retail and disposal) as a high proportion of their overall footprint.

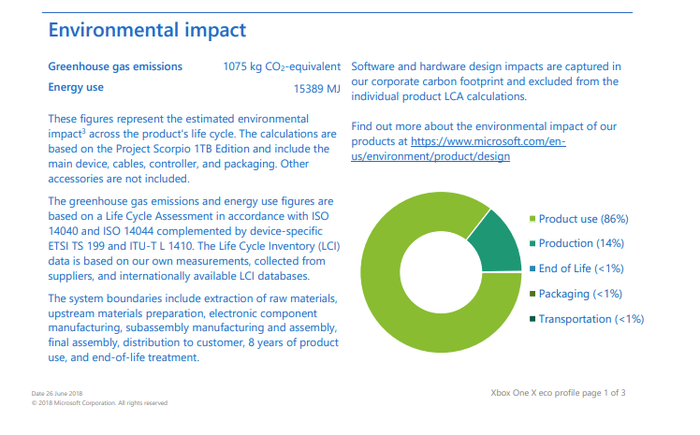

Consoles, in contrast, are much more weighted toward energy consumed during use. According to the publicly viewable Eco profile provided by Microsoft for its Xbox consoles, the Xbox One has a 1,114 kg CO2-equivalent footprint over an 8-year lifespan, including manufacturing and energy use. In its breakdown of environmental impacts, 82% of this footprint is caused by product usage, with another 14% from production.

Microsoft’s reporting on the energy use of an Xbox Series X over its lifetime shows that powering the console during use is the main contributor (Xbox One X Eco Profile)

On the development side, an indie game made by a core team of five will use up negligible energy compared to an Assassin's Creed with a workforce of a thousand. Only a handful of companies, such as Space Ape Games, have taken steps to extensively measure the environmental impacts across all their operations, though the number is growing. According to Ben Abraham’s Digital Games After Climate Change, the full carbon footprint of the whole games development sector is likely in the range of 3-15 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent per year, extrapolating from the handful of companies that do provide data.

No parallel attempt has been made to estimate the global carbon footprint of all devices used for gaming across every platform, using life cycle assessments to include all relevant stages. However, one recent study puts the annual energy usage from devices in the United States alone at 34 TWh, resulting in 24 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent, suggesting that a worldwide figure would dwarf that of game development by several times at least.

Following this trail further, the next question is to ask what kind of focus points and priorities present themselves across the three major categories of devices listed earlier. By sheer number, more people use phones and tablets than any other platform. PCs, on the other hand, use up much more average energy per hour and have a sizable userbase of well over a billion. Consoles have a relatively tiny install base compared to the other categories. Still, I believe consoles are the right platform to start with, given their unique role as gaming machines alongside other reasons I’ll go into below. Before looking at what can be changed, let's consider the situation today of the current generation, how it’s currently managed and how consoles have changed over time.

Consoles in history and the present day

Console energy use is governed by an industry partnership called the Games Consoles Voluntary Agreement (also called the Self-Regulatory Initiative), which was set up by the European Commission in 2012 to monitor and improve the environmental impact of consoles. Microsoft, Sony and Nintendo are all partners and have signed up to several revisions of the agreement in the past decade.

The most recent report, published in November 2020, covers a broad overview of the energy use of consoles and is the first to incorporate an analysis of the Playstation 5, Xbox Series X and Xbox Series S. The report, which was written by representatives of each manufacturer in partnership with the EU, details a number of improvements over earlier generations.

Firstly, the new consoles use less energy while in sleep modes than the previous generation. The PS5 consumes just 0.5W in rest mode, down from 4W used by the launch PS4 model. The Xbox Series X launched with a less impressive 12.4W instant-on mode, only slightly down from the 14W of the launch Xbox One, but Microsoft have recently changed the default power setting to shut down instead (0.5W).

Streaming video is also improved, with the PS5 averaging 53.5W for non-UHD content, down from the PS4's 96.7W (UHD support wasn't added until the PS4 Pro, but wattage is down on this front as well, from 84.2W to 75.7W). For Xbox, non-UHD content is down from 66.7W for the launch Xbox One to 51W on the Xbox Series X and 27W on the Xbox Series S.

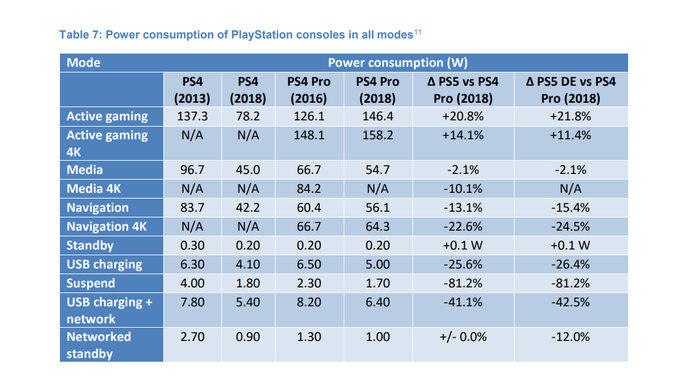

PS5 energy use across each mode, compared with various PS4 models (2020 SRI Report)

On the gaming side, the report uses two "Business As Usual" (BAU) scenarios of how the consoles could otherwise have been made, to stress how much more efficient they are at performing the kinds of processing and graphics tasks needed for video games than either the previous generations or a comparable gaming PC. The first BAU considers how the current generation would look if there were no technological improvements in terms of die shrink, CPU efficiency, GPU efficiency or storage type since the Xbox One X or PS4 Pro. BAU 2 takes a similar approach, using the Xbox 360 and Playstation 3 as comparison.

Unsurprisingly, the BAUs would have led to a massive increase in energy use. For example, the PS5 would have been pushed to 296W during active gaming in BAU 1 and all the way to 389W in BAU 2. Media playback would also have shot up, nearly tripling to 139.9W for the Xbox Series X in BAU 1 and reaching 240W in BAU 2, an almost five-fold increase. Overall, the total energy saved for the entire lifetime of this generation the first BAU scenario would have resulted in an additional 47.4 TWh of energy use from the current generation in just Europe alone, roughly the yearly electricity use of Portugal.

Reading the report, you'd easily get the impression that we're in an age of unprecedented ecological preservation, with no expense spared to minimise the impact of gaming. The problem is, there's nothing "usual" about the BAU scenarios in the real world context of technological progress. They have no grounding in the economic and technological conditions that consoles are actually made in and the energy "savings" made by comparison to each BAU don’t represent remotely plausible alternative situations. Computer technology changes at a rapid pace and at no point in the entire history of consoles has one generation been superseded by the next without any efficiency improvements at all. Moore's Law has proven remarkably resilient through the decades, most recently in the System-on-Chip (SoC) architectures that both sets of consoles have taken advantage of, but which are also widespread in phones, tablets and macs. It's also the driving force behind the existence of console generations in the first place. Imagining it doesn't exist, or might have stopped by now, leaves you with a world where it's hard to imagine these consoles would have been created at all.

In all its 51 pages the report pays scant attention to arguably the most critical piece of data of all: energy use during gameplay has gone up on average, compared to the last generation. The Xbox Series X uses 180W on average, compared to the Xbox One's 106W, while the PS5 uses 201W, up from the PS4's 137.3W (the figure for PS5 is taken from the Playstation website, as the report only had access to Astro's Play Room at the time of publishing). According to tests done by Eurogamer, the launch PS5 can draw all the way up to 230W, and the Series X 190W, while playing Cyberpunk 2077.

Image credit: CD Projekt Red

Image credit: CD Projekt Red

Cyberpunk 2077 is one of the most taxing games to run on the PS5 and Xbox Series S/X machines

To put these numbers into a more fitting context, I wanted to include a graph here of how home console wattage has changed over time, dating all the way back to the 1970s. Unfortunately, it's hard to find verifiable numbers for many of them so I will have to settle for some examples from this list, with the caveat that there may be small inaccuracies (if someone happens to have a power monitor and a large collection of old consoles, that would make a helpful research project).

The earliest consoles in the 70s and 80s, such as the Atari 2600, NES and Sega Genesis used tiny amounts of energy - less than 10W on average. Things started creeping up in the 90s with the likes of the Playstation, N64 and Dreamcast coming in at around 10-20W. In the early 2000s we have the best selling console of all time, the Playstation 2, along with the original Xbox. The numbers I've found indicate something in the range of 40-80W here. Then we have a huge leap upwards with the Xbox 360, which could draw up to 177W, and the PS3, which would often draw 200W while gaming. The following generation in the 2010s cut back a bit with the Xbox One (120W) and PS4 (140W). Meanwhile Nintendo changed its business strategy after having to sell the 2001 Gamecube at a loss, and thereafter stopped competing with Sony and Microsoft on graphical fidelity. The Wii (2006) used 18W, the Wii U (2012) used 33W and the Switch (2017) now draws up to 15W in docked mode. (Note: all the above are for launch versions of consoles, and don't include further revisions which cut down on energy requirements.)

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

The Atari 2600 drew 4.5W during use, which is about 2.25% that of a launch PS5 running a native PS5 game

So there we have it: in the last five decades consoles have increased in power usage about 10-20 times and the only console that can match the current crop for power drain is the PS3. The biggest jumps came in the 2000s, roughly in parallel with the rise of climate change as a major issue of concern in the public consciousness. All this raises the disturbing question of how any of this can, in any reasonable light, be considered an environmental win. The report makes literally dozens of references to "efficiency" in one form or another, but the fact that these are literally two of the three most power hungry consoles ever made hardly merits a mention, with just a note that "Gaming power consumption is the only mode where power has increased, due mainly to the substantial increase in performance between generations." That's a strange way to describe the mode which is the defining function of the devices in question.

It might seem unfair to compare machines released in 2020 to those from decades earlier, given the huge changes in computers, the internet, market expectations and technology in general. But that's exactly the point: all of these things are assumed to be primary factors which define how consoles are made, with other concerns limited to merely trimming around the edges. A design philosophy genuinely committed to sustainability would factor that in right from the start and then find ways to build products within that remit. The terms of the Voluntary Agreement itself state that its members must "Reduce the power consumption of Games Consoles to the minimum necessary to meet their operational specification while not limiting the industry’s ability to improve functionality and to innovate". In other words, they have to cut down on energy usage only to the extent that it makes no meaningful difference to the devices at all.

Aside from its questionable use of BAU scenarios, the report stresses the improvements Sony has made reducing PS5 power usage during sleep mode over preceding generations. But the standard of comparison here should be the sub-1 watts used by earlier generations that were designed to be conveniently turned on and off, rather than the last two generations which actively introduced sleep modes in the name of better convenience. In the process, the lowest energy uses have become more awkward: my old Playstation 2 used to boot straight into the inserted disc when turned on, whereas my current PlayStation 4 Pro doesn't even have that as an option. Mitigating a problem that has only very recently and deliberately been brought about is the very minimum we should expect.

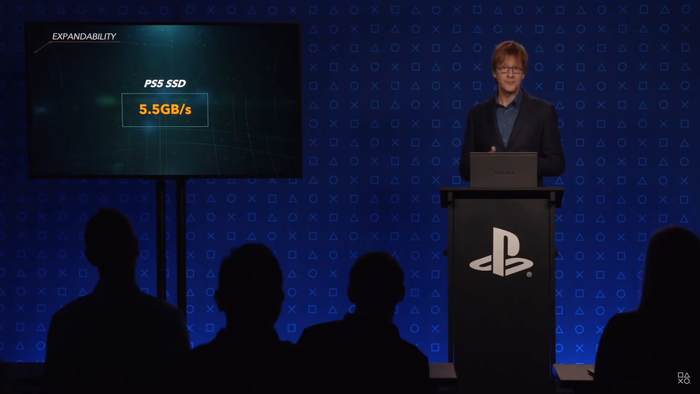

Mark Cerny explained how architectural improvements enabled an incredible leap in performance with the PS5, back in March 2020 (Sony Interactive Entertainment)

Perhaps the most worrying sign in the report is how it frames the capability of new consoles to output an 8K signal to displays. In the report’s own words: