(This article is a repost from my blog here and it's a followup to a previous Gamasutra post)

By 2015, using the Cerny Method the design students were able to create evolved prototypes of their game design. For example, the student above was able to create a Beat-Em-Up/RPG game within 10 weeks, and was able to showcase the game as a portfolio item along with other deliverables. Another problem then appeared: art. Or rather, designers forced to consider art issues. So this was the problem I tackled from 2015 till now.

This is MAMJ reviewing Light Up, a game by an all-designer team for their FYP. Having no programmers or artists on their team - which was the worst case scenario I was concerned would happen - they had to figure out how to deliver a fun, playable game. They settled on using RPGMaker and was able to deliver a horror game hacked into the engine.

The game was playable, created memorable responses among testers and MAMJ seemed to truly enjoy trying it out. As a proof of design, the game worked. We did however get a comment from the industry that the art is not impressive. This was settled by explaining the designers had no ability to work on the art, but it did made me realize that in the end, games are still judged by their art. Design, unfortunately, is obfuscated; you won't get it until you play it.

Now, if art blocks people from playing a game, is it possible for a designer to do something with art? Especially if they're stuck in a situation where they have no access to artists?

Should designers even consider dealing with art?

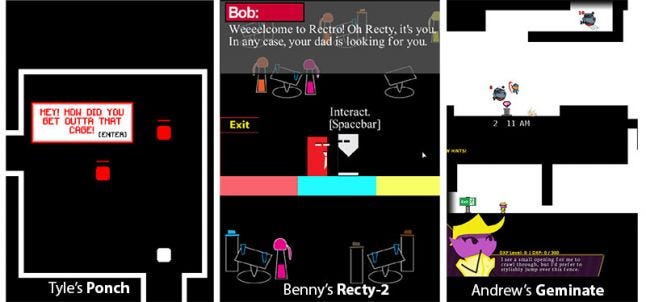

Design student prototypes circa 2014.

Design student prototypes circa 2014.

The fact is, design students come with varying abilities in art. Sometimes we do get 'purple unicorns': design students who can do art and programming thus are able to create a very tight integration of all three aspects in their prototype. Andrew Sin's Geminate (Image:right) is an example of this. However, we can't rely on students coming in as all-rounders and an educational program should be catered to an average expectation of what students can do. Expecting design students to be able to do art on their own is unrealistic. Furthermore, game design is best proven with prototype art. If a game is proven fun with ugly art, then good art can only make the game better. Benny Chan's Rect-y 2 (Image: center) and Tyle Ooi's Ponch (Image:left) are good examples: they both have serviceable art that allow players to test the game to see what the game can offer.

If there is one good reason to get designers to do art, it is because it will allow them to not wait for artists in order to prove their designs. The design students cited above were able to convey the experience they wanted by generating their own assets. This ability has two advantages:

Artists can be freed to work on other art assets needed.

Designers can confirm their designs without needing an artist to be available.

So if it's good for designers to have some art ability - but not be able to learn to do art by themselves - what should they learn in order to do a good game design?

How should designers deal with art?

This commentary is by Michael Ooi, a fellow game designer in our school. It's an interview I require all design students to see as it clarifies an important point: the designer's job is figure out how to make an idea work.

The purpose of design student creating a prototype of their game idea to demonstrate how it should work if fully implemented in a game, thus providing a guideline for a programmer to follow. As the idea is represented in-game, the programmer sees how the idea is expressed and could work out how he or she would implement in the game engine of choice. In other words, by prototyping the game, the designer has helped the programmer determine the features needed and how the feature should function, with the actual play of the prototype providing parameters that the programmer could implement.

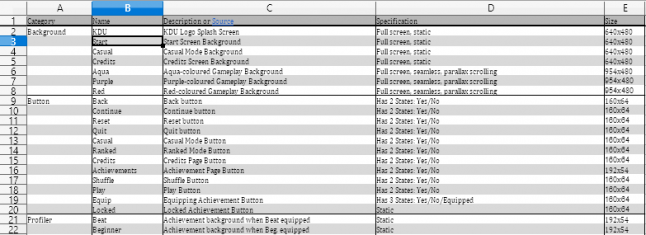

A similar idea can be applied to art. Designers don't need to create art. They just need to be able to define how the art should work. By creating placeholders in a prototype, designers should be able to determine the dimensions of the art assets needed and answer questions on how the assets should work (e.g. What are the dimensions of the asset? Is it an animation? If yes, how many frames?). This alone is already handy: artists can use the parameters created by the designers and recreate the assets, knowing very well that correctly implemented art would fit into the game.

Art asset list sample.

Art asset list sample.

In the end, they're technical parameters. Useful for programmers and artists, but is there more information a designer can confirm for the other members of the team? What details can a designer work out for art that goes beyond technical parameters?

Industry examples: Mockups and Reuse of In-Game Assets

An ex-colleague, Johaness Reuben, espouses the use of mockups to test concept of a game before going into the design in further detail. Joh was a Technical Art Director in my old company, thus was able to handle art and tech issues by himself. For him, creating mockups is within his skillset.

One of the rules I use in planning out education is that what I teach must be applicable outside of the Uni. There is no value in teaching students in a skill using a specific software, and have the skill be unusable if the software isn't available at work or the skill is non-transferable to other software. What has changed compared to ten years ago was that software that used to cost hundreds of dollars to own is now cheap, and there are free versions available. Adobe Photoshop for example has been an industry standard for a good while, and to own a license to use it under the Photographer license is cheap. Furthermore there are free options with GIMP and Krita.

In this context, it makes sense to get designers to be fluent in Photoshop, or at least in the fundamentals of digital image manipulation. If the company would not provide the tool, they can use the free options, or own a license forgoing two ice-blended coffee drinks a month (your exchange rate may vary). What's important is that understanding digital image tools would allow them to create their own art assets.

(Caveat Emptor: all of our students are required to go through a Fundamentals of Art module, which means they learned how to Photoshop. This means I have the confidence all design students I meet in the program will know their way in Photoshop).

What can they do with Photoshop? Well, a Wired interview with Donald Mustard of Chair("Lightning-Quick Prototypes Brought Infinity Blade to Life" by Chris Kohler) brought an interesting example: it showed how Chair used their old game assets to test out their game ideas.

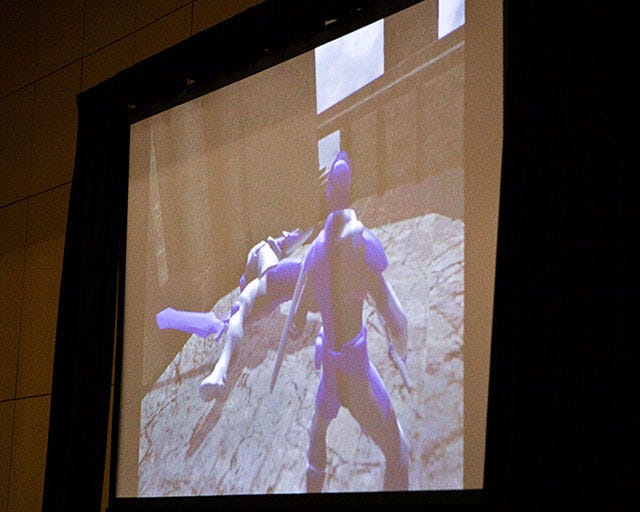

Next, Mustard showed the first playable prototype of the game (above), which used character models swiped from SHADOW COMPLEX. It already had many of the features that would end up in the final product, like the ability to swing your sword, defend and parry enemies’ attacks.

This version was ready to roll after only 10 days of development. At this point, he said, players were already enjoying the parry-and-attack gameplay.

From https://www.wired.com/2011/03/infinity-blade-prototypes/ : Chair Entertainment's Donald Mustard showed early prototypes of his iPhone game Infinity Blade at GDC 2011. Photo: Jon Snyder/Wired.com

From https://www.wired.com/2011/03/infinity-blade-prototypes/ : Chair Entertainment's Donald Mustard showed early prototypes of his iPhone game Infinity Blade at GDC 2011. Photo: Jon Snyder/Wired.com

Chair was able to test their design at speed because they have game-ready art assets at hand. I have spoken with another game developer and she confirmed that when the designers in her company wanted to test out game ideas, they would scavenge old art assets for re-use. What was important was the ease for the designers to find assets they could use to test their ideas; belonging in an established company meant being able to use what the company already has collected over time.

I realized that what would speed up designer testing was quick access to in-game ready art assets. This is precisely what student developers don't have; unless the University or college has accumulated pre-existing game assets by senior students or collected/purchased existing art assets, every project ends up requiring art assets made from scratch.

However, the Internet is a treasure trove for existing art assets. Search for game sprites on Google and there's plenty to find. One could also go to Spriter's Resource, BGHQ and many other - easily searchable - game art asset compilation sites. The only problem is that it would be illegal and unethical to use them in a commercial project.

Obviously the students should not be using existing art if they desire to publish their game. Prototyping however is a different story. Prototypes aren't meant to be published, and a prototype's goal is convey working concepts as quickly as possible.

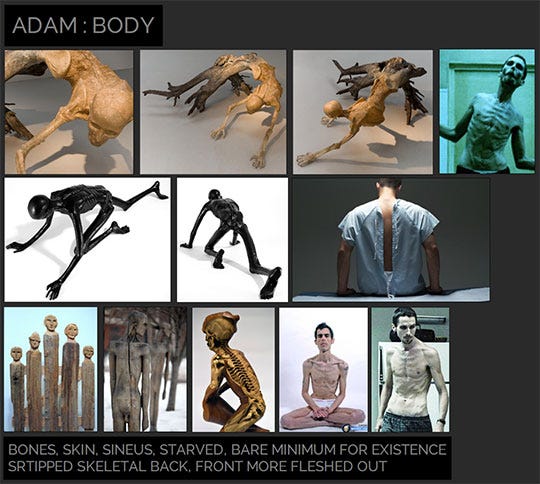

Reference images for the concept of Adam, from https://blogs.unity3d.com/2016/07/07/adam-production-design-for-the-real-time-short-film/ by Georgi Simeonov.

Reference images for the concept of Adam, from https://blogs.unity3d.com/2016/07/07/adam-production-design-for-the-real-time-short-film/ by Georgi Simeonov.

For example, in creating the Unity short film Adam, images that are most likely copyrighted are used as a reference tool. The point of using them is to convey ideas that would help the developers flesh out the final concept. These images will not be used in the final product; they are a base for ideation in order for the developers to arrive to the unique, workable concept.

I needed to see if allowing the use of existing in-game art would assist design work the same way. Since a design pitch could be a "this game with X", a design student could quickly do visual test of how "this game with X" would be. If this efforts leads to a greater understanding of how the idea work/does not work, then the design student has clarified details that would be useful to the programmers and artists in his or her team. This provides more value to the designer's concept that just 'providing an idea'.

Tackling Technical Illiteracy

Once I considered the possibility of using existing in-game art, I realized it opens the process to several strong advantages.

Mockups can be easily done if all game art is allowed. Which is good as a designer can confirm whether or not the screen design for the game idea works as quickly as possible. A design student can scour the Internet and create a collage representing the idea within a couple of hours. Visualizing a 2D game in mockup form would the designer solve 2 out 3 C's from the Cerny Method: