Author: by Marie-Josée Legault, Johanna Weststar

This feature contains a decade's worth of information on how long developers really work -- culled from surveys given to game developers and interviews with them.

The data was crunched by academics who know the subject well: Marie-Josée Legault, Professor in Labor Relations, Téluq-Université du Québec, and Johanna Weststar, Assistant Professor, Management and Organizational Studies Department, Western University.

The pair previously contributed "Are Game Developers Standing Up for Their Rights?", which also tackled quality of life issues, to Gamasutra in 2013.

Introduction

The video game industry is an object of unrelenting criticism about its working conditions and is often accused in social media of treating its developers poorly. According to the 2014 Developer Satisfaction Survey (DSS) survey of the International Game Developers Association (IGDA), 32 percent believe that there is a negative perception of the game industry. When asked why, working conditions was the top response (68 percent), just before sexism in games (67 percent) and perceived link to violence (62 percent) (Edwards, Weststar, Meloni, Pearce & Legault, 2014). Among those engaged in core game development roles this number rises to 77 percent (Weststar & Andrei-Gedja, 2015).

The labor issue of working time stands out among others that besmirch the industry’s image: discretionary rules in establishing wage levels, in appointing to projects, in attributing credits, insufficient intellectual property rules and funds for updating knowledge; lack of job security and arbitrary hiring and firing decision processes; non-disclosure and non-competition agreements that may end up in legal proceedings.

Long working hours have become an inescapable feature of the industry where developers are often bound by contracts that do not include any terms and conditions of employment relating to hours of work and normal working hours or any policy regarding overtime work and compensation.

Let’s account for the facts related to the evolution of working time among video game developers over the latest 15 years.

To do so we focus on game designers, interaction and level designers, programmers, 2D and 3D artists, audio artists, writers or narrative designers, localisation experts, etc. We are not including quality testers, managers, nor team leads.

Our discussion here is informed by the data collected in three IGDA surveys:

2004 Quality of Life (QoL) survey (1000 respondents);

2009 Quality of Life (QoL) survey (1145 respondents in the developers sub-sample);

2014 Developer Satisfaction Survey (DSS) (795 respondents in the developers sub-sample).

The IGDA is a non-profit membership organization of individual creators of video games. In 2004, the IGDA launched its initial Quality of Life (QoL) survey to gain a clearer understanding of some employment issues – from “crunch time” to compensation issues. In 2009 and 2014, the IGDA partnered with us to develop a new version of the Quality of Life survey and to process and analyse its results. This allows us to compare three milestones in the young life of this industry to take stock of the evolution in the international industry’s issue of working time.

As part of our research we have also conducted 147 interviews with developers in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver. We have written a more complete report on the trends in working time that includes some discussion of this interview data as well as more survey data, additional detail about our methods and an account of the legal framework regarding overtime in the US and Canada.

A general decrease in regular hours of work

The IGDA surveys distinguished between two different targets in investigating regular hours of work among respondents: the hours developers are expected to work and the hours that they actually work.

Hours management expects developers to work

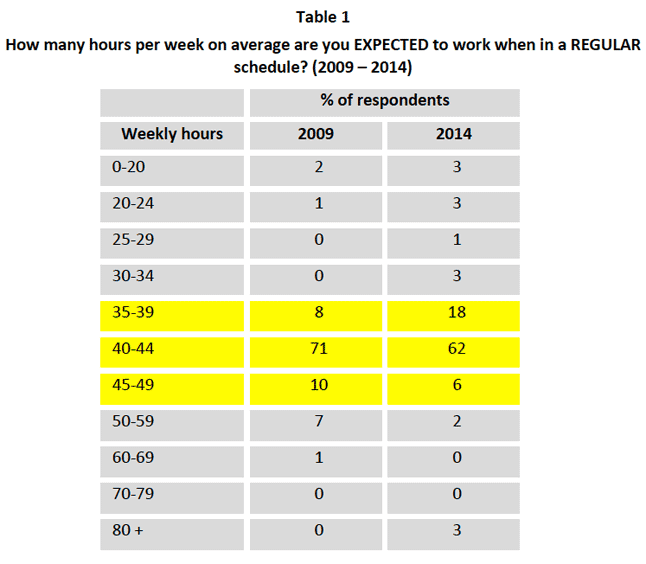

First, we can observe the management’s expectations regarding the length of the regular work week, as perceived by respondents. This question was first asked in 2009 so we can now see how the situation has changed in 2014.

Table 1 shows an improvement in the respondents’ perceptions of managers’ expectations. In 2014, a larger share of respondents than in 2009 reported that their studio management expects them to work 35-39 hours per week when not in crunch time. This category is what we would consider ‘normal’ hours in a ‘standard’ work week. Fitting the same trend, compared to 2009, a smaller share of respondents in 2014 felt that their studio management team expects longer hours (between 40 and 49 hours a week) as a regular work week.

Hours developers actually work on regular days

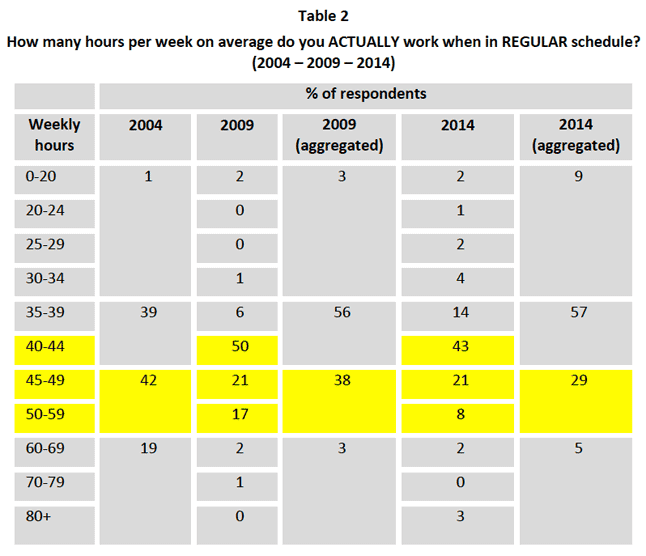

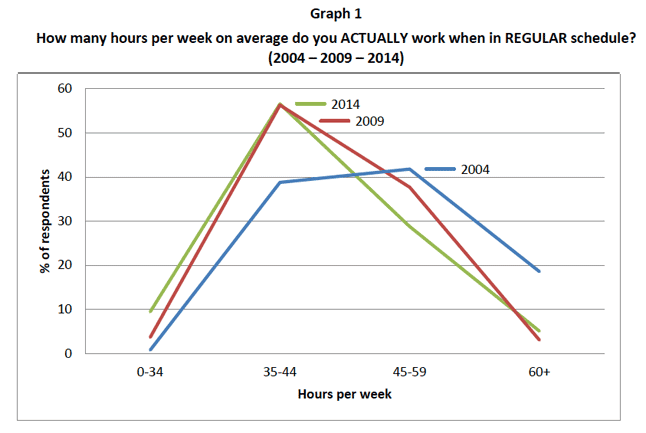

In the long run we observe a general decrease of the regular working hours over 2004-2014. This means that there is an increase in the 35-44 hours bracket between 2004 and 2014 and a decrease in the longer duration categories.

In 2004, 40 percent reported working 44 hours or less per week. This increased dramatically to 59 percent in 2009 and increased again slightly in 2014 to 66 percent. Over the same time period fewer respondents reported working more than 45 hours per week: 61 percent in 2004, 41 percent in 2009 and 34 percent in 2014 (Table 2).

This data also indicates that the number of part-time employees in the industry might be rising since there is an increase in the number working less than 30-34 hours per week. As the game industry is not known as a sector where you can find part time employees, this requires deeper investigation.

Note: We have arranged data here to take advantage of more detailed data in 2009 and 2014, and still manage to compare the outcomes of the three surveys.

Graph 1 illustrates this reduction in actual hours of work in a regular schedule between 2004 and 2014. As discussed above, it highlights a greater concentration of respondents in the shorter durations in 2009 and 2014 when compared to 2004.

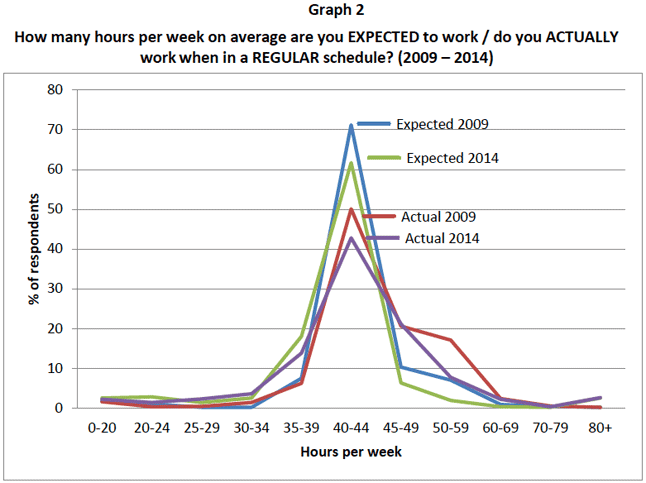

To take advantage of the more detailed data collected since 2009, we can also compare the expected hours of work to the actual hours of work. Graph 2 shows that the reduction in the hours of work between 2009 and 2014 has been both in terms of management expectations and actual hours worked. However this graph also shows that developers still tend to work more hours than they are officially expected, though this gap may be smaller in 2014.

A decreasing practice of crunch, but still important

Crunch time, a project management notion

For the purpose of the IGDA survey, crunch time was defined as when a team goes into an extended period of work (beyond the regular hours) to meet milestones and deadlines for shipping deliverables. Known as overtime to most people outside of the industry, the use of the word overtime is carefully avoided in the video game industry. Though the phenomenon itself is common to project based environments, the virtually exclusive use of the term crunch in place of overtime is characteristic of this industry.

Crunch time is a threefold notion, as workers can be asked to:

add working hours to the regular weekly working hours and the length of the work week varies between 45 and 90 hours;

extend this practice over a few weeks or a few months;

repeatedly engage in discrete periods of crunch over the course of a project or over a certain time period

To understand this multi-faceted nature of crunch, we then have to consider how many hours developers work in crunch, how long a period of crunch extends and how many times they crunch over some defined time period (i.e., over the course of a year). We also must acknowledge the variation in crunch practices across studios. In some studios crunch is standard practice, rather than the exception. In some others, it’s nearly banned.

The general practice is decreasing, but is still part and parcel of the trade

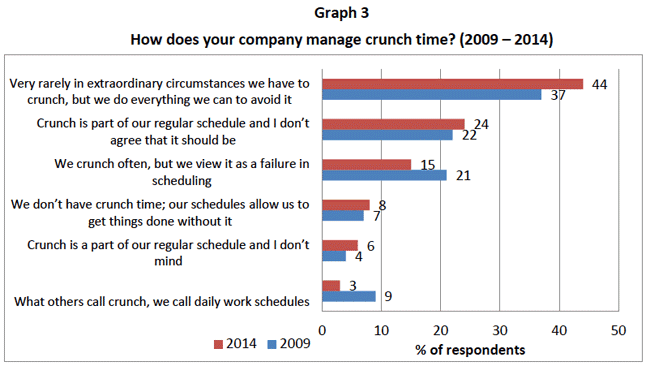

First, the 2009 and 2014 surveys asked a question that allows us to compare the studio practices related to crunch time. As Graph 3 shows, the share of respondents who said that their studios do all that they can to avoid crunch has increased from 37 to 44 percent.

If we combine the first two sets of answers on Graph 3, we get the proportion of respondents who consider the practice of crunch as an exception to the rule in their studio. This has increased from 44 percent to 52 percent over the five year span.

If we combine the last four answers, we get the proportion of respondents who perceive the practice of crunch to be part of the regular schedule of their studio. This has decreased from 56 percent to 48 percent.

These numbers are trending in the right direction, but a high proportion of developers still work at studios where crunch is common and even accepted.

The 2014 survey asked for the first time if respondents had experienced crunch time in the past 2 years. The data show that 21 percent of our respondents have not experienced crunch in 2014. Still, that means that three quarters of the respondents have experienced crunch in the last 2 years, which means it’s still part and parcel of the trade: 19 percent experienced crunch once, 19 percent twice, 42 percent more than twice (Legault & Weststar, 2015:15).

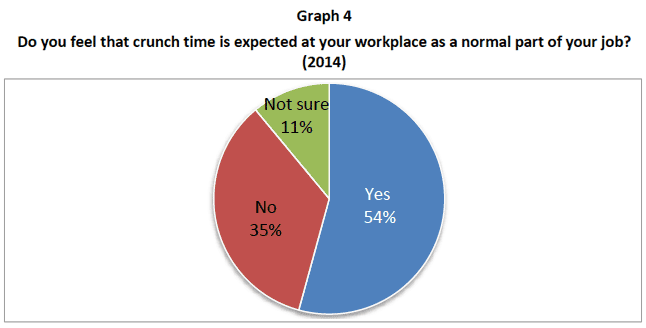

The next question (Graph 4) was also asked for the first time in 2014. Again, we must acknowledge that more than half of the sample considers crunch time as part and parcel of projects or video game development.

This gap between expected hours (the perceived managerial norm) and actual hours, contrasted with 21 percent of respondents reporting that they have not experienced crunch, raises the issue of the ability to take the “refusal stance”.

Is it possi

No tags.